Julie Keys reviews Sleep by Catherine Cole

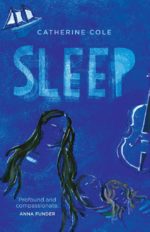

Sleep

Sleep

By Catherine Cole

ISBN:978 1 76080 092 5

Reviewed by Julie Keys

‘Will You forgive me?’ Monica asks her daughter, Ruth, in the opening paragraph of Sleep.

‘Forgive?’ I thought. What is there to forgive?’ (1)

As a child Ruth does not understand the angst behind her mother’s question and is dismissive of it. The memory, however, leaves an indelible mark, one of many that resurfaces as she tries to understand her mother’s life and her death.

Ruth is seventeen and a schoolgirl when she meets the elderly French artist, Harry, in a café in London. There is a bond, a recognition of similarity in one another as they converse. Both have experienced trauma and loss. Ruth’s mother has died, and Harry grew up in Paris before and during its occupation in World War II. It is in sharing their stories that a friendship is formed.

Ruth and Harry’s tales intertwine. Author Catherine Cole takes us back to Harry’s childhood in Paris, to the quirks and allure of life beside the Canal St Martin. We hear the voice of his mother calling him from a fourth-floor window. There is his aunt’s cello, his fascinating and vibrant twin cousins. We witness the exact moment Harry stands beside his father observing a painting and decides he will become an artist. This comfortable and contented life sits alongside a shifting political climate. Some ignore the changes but the more vigilant escape Paris and France while they have the chance.

Like Harry, Ruth talks about her family. The resilience of her sister Antoinette and her father, family outings, the sleep therapy that had been the treatment of choice for her mother’s depression as a young woman, and the mother she knew with her increasing propensity for sleep: ‘She’d begun to sleep anywhere: at the kitchen table, on a blanket in the garden, on any one of our beds’ (133).

Trauma, loss and shared memories are not new subjects for Cole. The author of nine books, her work reflects a range of interests and eclectic skills that includes fiction, non-fiction, memoir, literary, crime and short stories. Sleep is an extension of the themes of love, migration, forgiveness and refuge first explored in her short story collection, Seabirds Crying in the Harbour Dark (2017), shortlisted for the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards in 2018. Just as the impact of an elderly artist in the life of an up and coming student was initially examined in the author’s memoir of her friendship with A.D. Hope in The Poet Who Forgot (2008).

Skill and experience are put to the test in Sleep as Cole delves not only into the complexities of these issues but steers away from a traditional plotline – a choice that highlights the novel’s intricate themes and serves the narrative well. This is Ruth’s version of events, her recollections. She narrates the story from a present-day visit with her Great Aunt Elsie and from the safe haven of the Yorkshire Dales. The plot emerges via a kaleidoscope of memories, beautifully rendered passages that draw the reader into each moment as the story finds its shape and unfolds.

Elsie is a natural counterpoint to the memories that consume her niece. She is lucid, sharply outlined, rooted in practicality, a contrast to Ruth’s mother Monica and her torpid life. Elsie has her own memories of Monica, revealing previously unknown layers to Ruth. She moves around her house and Ruth’s life ‘setting things to rights’(32). There are pots of tea, the smell of lavender, stories about the war and the depression. She bids Ruth not to spend her time on Harry’s stories at the expense of her own and warns, as her mother once warned her to ‘be careful what you remember and when’ (33).

Cole brings a familiarity to the settings – London, pre-war Paris, and the Yorkshire Dales – and is tender in her portrayal of Monica, ‘a shadowy figure behind the door, a lump of sadness on the battered couch, a pair of long white feet under a red and purple hippie skirt. Hair across her face, she weaves, moans’ (161). But Sleep does not always follow a comfortable line. As a reader, I felt unsettled over Ruth and Harry’s meeting. Was it really the result of chance? There was also some discomfort in observing Ruth and her growing obsession with unravelling Monica’s past as she tries to forage out those who might bear some responsibility. As in life, nothing is straight forward and moments of ill ease provide fuel for reflection.

Harry reminds us that despite trauma there is the possibility of resolution. For him art is the healing salve, the restorative that has provided some balance to what has happened in his life: ‘Art allows us to make something lovely of self-delusion and pathos and longing and fear.’ (105). Harry is his most persuasive as he encourages Ruth to find the art in her own life. The conversation between the older Harry and the younger Ruth who equate with the past and the present, threads its way through the narrative debating the conundrums. Can we always forgive regardless of the circumstances and is consolation a worthy alternative to justice?

Harry argues that; ‘You must forgive. Revenge hurts only those who desire it’ (63), all the while understanding that it is Ruth’s decision to make.

In her acknowledgments Cole describes Sleep as ‘a generational conversation about art and loss [that] speaks also of the need to ensure that we learn from history by understanding how easily past horrors can resurface while we sleep or turn a blind eye.’ (246). In this sense Sleep is a timely novel that extends beyond the last page as we ponder the shifts in the world around us and contemplate how our own somnolence has contributed to the social, environmental and political catastrophes that to some degree we now live with and have come to accept.

JULIE KEYS has recently completed a PhD in Creative Arts at the University of Wollongong. Her Debut Novel The Artist’s Portrait was shortlisted for the Richell Prize for Emerging Writers in 2017 and published by Hachette in 2019.