William Farnsworth reviews Glass Life by Jo Langdon

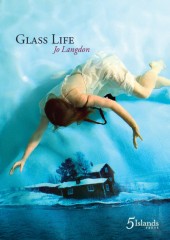

Glass Life

Glass Life

by Jo Langdon

ISBN: 9780734054272

Reviewed by WILLIAM FARNSWORTH

On opening the first pages of Jo Langdon’s second collection, Glass Life, one might, at first, have the sense of reading through a poet’s travelogue. Among the first few poems there are descriptions of the modernist Hauptbahnhof station in Berlin or the glaze ice sculpture of the nativity scene (Eiskrippe) in Graz, Austria. Here, a theme integral to the collection is implied: fragility and strength in balance with each other; a starting point for Langdon’s lyrical journey of introspective musings and wanderlust.

=================================Sorry you must be logged in and a current subscriber to view the rest of this content.

Please login and/or purchase a subscription.