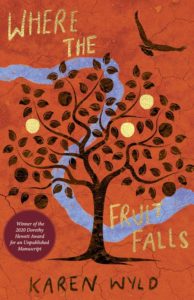

Anne Brewster reviews Where the Fruit Falls by Karen Wyld

Where the Fruit Falls

Where the Fruit Falls

by Karen Wyld

ISBN: 978-1-76080-157-1

Reviewed by ANNE BREWSTER

Karen Wyld’s Where the Fruit Falls is an important new novel in the field of Australian Aboriginal literature and a tribute to the work of UWAP under the stewardship of its out-going director Terri-Ann White who, as Wyld says in her Acknowledgements, ‘helped grow UWAP into a treasured Australian publisher’.

It tells a powerful story of an Aboriginal family, focusing largely on the young woman, Brigid, and her twin daughters Victoria (Tori) and Maggie, and their journey to find family, reunite with Country and discover the inland sea where the ‘giant aquatic creatures’ and ‘wondrous beasts’ (287) of Aboriginal cosmology reside. On this journey they struggle against the brutal impacts of racism in rural and metropolitan settings. There are references to the effects of the Protection Era and other events such as the Maralinga bomb tests.

The title refers to the central image of the two very different trees in Brigid’s life, the apple tree of her non-Aboriginal grandmother’s garden (which could be a reference to British colonial immigration) and the Bloodwood tree (and its fruit, the bush apple) under which she was born, shown to her by her Indigenous nana.

There is a striking image of the two trees intertwined at a critical nexus in the narrative. Brigid had grown up with the trees, fruits and plants of her non-Aboriginal grandmother’s garden, and although she has an immense affection for her grandmother who had largely raised her, she has to painfully unlearn her grandmother’s indoctrination that she (Brigid) is a potato: ‘her skin might be brown like the earth, but inside she was [white] just like everyone else’ (12). Despite the damage her grandmother had wreaked in her life, Brigid continues to love her, and to respect the role that trees had in the lives of immigrants’ such as her grandmother.

She tells her Jewish friend, Bethel, whose partner, Omer, had carried a small olive sapling all the way from his homeland to Australia, that ‘my granny also brought treasured saplings from her country … she’d planted them with purpose, to set down stronger roots in a country strange to her. Those trees from her home country helped her to create a new home, for a new family’ (98). In the affectionate portrayal of Brigid’s grandmother and the image of the intertwined bloodwood and apple trees, Wyld seems to be figuring Brigid’s complex and nuanced bi-culturality, or at least the continuing (and sometimes contestatory) interplay of her dual heritages.

The novel demonstrates that racism against Indigenous people remains a constant in colonial and post-colonial (ie the federated) Australia, with even more recent immigrants, as Bethel complains, treating First Nations people ‘with disdain’ (77). However, as Bethel and Brigid’s friendship indicates, First Nations people’s connectivities are multidirectional, and her friendship with Bethel and her partner Omer is vital and life sustaining. Omer observes that war, horror and inhumanity come in many forms and impact many peoples, producing loss and trauma. He suggests that, like many people across the globe, Indigenous people are ‘still engaged in a combat of sorts’ (77). We realize that, in his vocation as an opal miner, Omer has both material and imaginative access to the inland sea for which Brigid searches, with its ancient archive of huge ‘wondrous’ creatures and the ‘carnage’ (288) they index.

In its portrayal of Brigid’s twin daughters, one of whom is dark (Tori) and the other light-skinned (Maggie), Wyld’s novel strenuously uncouples Aboriginality from biology and skin colour. In a powerful narrative, which recalls Tony Birch’s intensely moving recent novel, The White Girl, we see the painful impact of the difference in the way white-skinned Aboriginal people have been treated by white settler-Australians. The many biting ironies of the scopic regime are played out painfully and, occasionally, with wry humour, in Maggie and Tori’s lives.

Brigid and Tori, in particular, struggle with a sense of not belonging, of being outsiders. They are on a journey seeking their family and Country, reminiscent of Sally Morgan’s iconic text My Place. It is indeed fitting that Morgan provides the cover blurb, in which she notes that ‘this evocative family saga celebrates the strength and resilience of First Nation women’. In spite of the lethal impact of violence in their lives, Brigid and her daughters are, in Tori’s words, ‘strong, independent and fearless’ (233). They defend themselves and each other from the corrosive effect of racist ‘hate’ and the brutal necropolitical drive of colonization, with strength and determination. They sometimes struggle to strengthen their Aboriginality, supported by their connections with birds and trees, with shadowy creatures in the world around them, and with stories from their ancestors.

Wyld also demonstrates the significance of global anti-racist activism from the 1960s onwards, referencing various movements such as the American civil rights movement and black power, borrowing an iconic image to salute ‘the fire in the belly of black peoples fighting for rights’ (287). She shows how the discourse and iconography of global activism gave many Indigenous people in rural and metropolitan Australia the tools to analyse history and to re-shape their understanding of themselves as a collective. Numerous Aboriginal novelists have mapped in fiction the intersection of politicized Aboriginal activism and personal transformation; Tori’s incipient emergence from suffering and struggle reminds us in some respects of Sue Wilson’s consciousness-raising journey in Melissa Lucashenko’s paradigm-shifting novel, Steam Pigs.

Wyld’s homage to global activism is complemented with local references, in for example, what seems to be a nod to South Australian ex-premier, Don Dunstan, who makes an appearance at a political rally that Tori and Maggie attend, as ‘a white man in tiny pink shorts, a white figure-hugging T-shirt and long white socks’ (296). The extra-diegetic references in the novel and Wyld’s interest in the impact of political activism on her protagonists indicate the proximity of some Aboriginal fiction to political activism. In her Author’s Note for example, Wyld suggests that ‘the call for action … often lies hidden in fiction’ (341); she adds that she sees this novel as working to ‘reimagine a more just and truthful present and future’ (341).

The novel’s narrative climax, which unmasks the shocking effects of toxic white masculinity, raises deeply disturbing questions about the graphic representation of racialised and gendered violence and race crimes. It resonates with the broad scholarly field of research on trauma and witnessing, bringing a unique Aboriginal iconography to this field, in the imagery of the three black birds which are Brigid’s witness. (One might also recall the crows in Alexis Wright’s Plains of Promise.) In Where the Fruit Falls the toxic white masculinity is offset with the presence of several benevolent, wise, compassionate and resourceful Aboriginal men who adjudicate in the rendition of justice according to Aboriginal protocols (recalling the Aboriginal male elders’ adjudication in Roo’s conflict with his girlfriend’s brother, in Melissa Lucashenko’s second novel Hard Yards).

In a recent article in the Journal of Australian Studies, Indigenous studies scholar, Clint Bracknell, notes the ever-increasing non-Indigenous interest in and demand for Indigenous cultural texts and analyses the impact of this demand on Indigenous researchers and communities. He talks about the lack of space and time for communities to “claim, consolidate and enhance our heritage and knowledge amongst ourselves” (Clint Bracknell JAS, 44.2 :213).

The racialised graphic commodification of Aboriginal women’s bodies which Where the Fruit Falls puts under the spotlight (while simultaneously deftly removing it from that spotlight through the wise actions of the Aboriginal men) raises questions about the non-Aboriginal reader’s presence in conversations about Indigenous literature. As a non-Indigenous reader and reviewer of Indigenous literature I am aware of the implications of Bracknell’s comment for my own work in this review. I aspire to join an ethical conversation about Indigenous literature with Indigenous and non-Indigenous writers, scholars and commentators in a way that is mindful of the conditions of commodification of Aboriginal bodies and texts and seeks to acknowledge and not encroach upon the Aboriginal space that Bracknell identifies.

ANNE BREWSTER is Honorary Associate Professor at the University of New South Wales. Her books include Giving This Country a Memory: Contemporary Aboriginal Voices of Australia, (2015), Literary Formations: Postcoloniality, Nationalism, Globalism (1996) and Reading Aboriginal Women’s Autobiography (1995, 2015). She is series editor for Australian Studies: Interdisciplinary Perspectives.