Brook Emery reviews Motherlode and Not A Muse

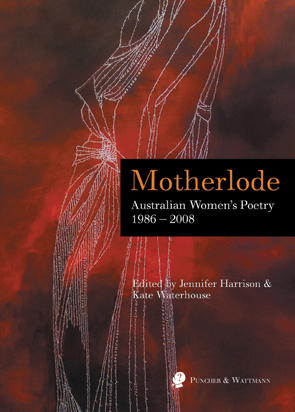

Motherlode: Australian Women’s Poetry, 1986-2008

Jennifer Harrison & Kate Waterhouse (eds)

Puncher and Wattmann, 2009

ISBN9781921450167

www.puncherandwattmann.com/pwmotherlode.html

Not A Muse

Not A Muse

Kate Rogers, Viki Holmes (eds)

Haven Books, Hong Kong

ISBN 978-988-18094-1-4

http://www.havenbooksonline.com/books/catalogue/not-a-muse

Reviewed by BROOK EMERY

What are my credentials, or lack thereof, to review these two anthologies of women’s poetry?

Despite an androgynous first name, I am a sliced-white-bread, baby-boomer male. Husband not wife. Father not mother. I am also instinctively uneasy with categorisations that assume difference based on gender. Boys Book, Chick Lit – leave me out. Men analytical, women emotional; men aggressive, women nurturing – stop it! Men’s movements re-discovering the bear or hunter in themselves, women learning to be assertive – how sad. Single sex schools – indefensible, an admission of failure. Once, after a reading, I was told by one poet that my ‘sensibility was very feminine’ and, almost immediately afterwards, by another poet that my ‘voice was so masculine’. What to make of this? (That difference is in the ear of the beholder?) What to do? (Shrug and laugh?)

But biology and evolution cannot be denied, and neither can social conditioning, nor entrenched beliefs and prejudices, and historically, politically and culturally it was, and, unfortunately, maybe still is, important that spaces are made for ‘women’s writing’, though something will have to be done about such a term because it implicitly defines itself not just against the non-existent term ‘men’s writing’ but against ‘writing’ .

Perhaps it’s not so strange that I should have felt compelled to question my reviewing credentials as, in their own ways, the editors of each book exhibit a little nervousness about the reception of their projects and feel a need to position their anthologies within the history of feminism and so-called post-feminism. Harrison and Waterhouse write in their joint introduction to Motherlode:

We have been asked whether this is a feminist book and it undoubtedly is, if feminism is defined as that which women know and strive to make known.

They acknowledge that much has changed in the lives of women as a result of feminism but identify the enduring experiences as:

the realities of fertility, pregnancy, birth and the bonds between mothers and their mothers, daughters and sons.

The editors of Not A Muse: the inner lives of women are more political. Kate Rogers writes that the book explores,

how we define ourselves as women. Are we living our lives honestly, completely true to ourselves? If we choose an unconventional life, what are the costs? Not a Muse is, in part, about our choices. How we define ourselves as women and poets. How we define freedom.

Viki Holmes asks rhetorically, ‘To what end an anthology of women only in this post-feminist era? Shouldn’t we be looking beyond divisions of gender in the 21st century?’ She doesn’t really answer these questions specifically other than to assert a right, or need, to speak and occupy the foreground:

Woman as mysterious, retreating Other; an enigmatic figure retreating in the distance, inspiring and intriguing – and silent. But what happens when the muse speaks? Not a Muse began as an attempt to redress this relegating of women to be sources of inspiration rather than creators. The voices in this anthology speak eloquently, reflectively, and with certainty, about the roles women have chosen for themselves – perhaps enigmatic, certainly inspiring and intriguing – but never in the distant background.

In a preface, ‘On Reading Woman’, the Indonesian poet Laksmi Pamuntjak tackles possible objections to the anthology even more directly. She asks:

Aren’t the days of being jumpy at the very mention of the word ‘female’ or ‘feminine’ finally over, because women have advanced by leaps and bounds to assert themselves as a subject first and foremost, of which ‘woman’ is only part? … Hasn’t women’s liberation gone to such amazing lengths that many modern-day feminists now even believe that the very concept of woman is a fiction, thus raising the possibility that the concept of women’s oppression is finally obsolete and feminism’s raison d’etre has fallen away?

More pertinently: do we still need an anthology of women’s writing? Does it not seem an endorsement of the gender polarisation that women have fought so long and hard to batter down?

Her answers to the last two questions are unequivocal: ‘yes’, then ‘no’. They rest. in part, on an undeniable political truth: ‘ in many parts of the world where women have no voice, no discourse, no place from which to speak, defining the ‘feminine’ is a luxury that cannot be corralled into the collective’.

Really, neither book needs an apology or a theoretical feminist defence. The impregnable defence of both anthologies is just that they are artful, interesting explorations of human experience. Each one demonstrates the power of good poetry to engage people on emotional and conceptual levels not easily accessed by other means. How much more powerful, subtle and informing these poems are than shelves full of theory, therapy or self-help.

Motherlode is a great title playing as it does on all the resonances of exploration, mining and discovery, of richness, abundance and centrality, while gently ghosting the homophone ‘load’ with its connotations of weight and burden. With 125 poets, 172 poems, and at over 300 pages it is abundant indeed. Published by the innovative and relatively new Sydney publishing house Puncher and Wattmann, it is also a beautifully produced book, attractive to look at and to hold. The cover is flexi-case which is closer to traditional hardcover than soft cover, there is a headband at the top and bottom of the spine, and even an attached bookmark ribbon. The binding is stitched, the paper gorgeous, and it is sharply printed and laid out: the packaging does justice to the content.

The focus of Motherlode is clearly defined and circumscribed. It is dedicated to ‘our mothers’ and is not designed to include all shades of female experience but to explore the experience of motherhood and to make this accessible to the general reader. The anthology is divided into twelve sections: nature, icons, pregnancy, birth, infancy, sons and daughters, daily grind, loss, old wives tales, mothers and grandmothers, the world, this last retreat.

The editors suggest that the anthology be considered as a collective narrative and they invite us to read it sequentially as one would a novel. This can work, as poem after poem seems to be a conversation with and a departure from the one preceding it. To read it thus is, perhaps, to impose a narrative consistency and might lead to the temptation to construct archetypes corresponding to the section headings. Thus, to take for example the section heading ‘Birth’, the reader might move from ‘I am waiting / for what emerges / from the white edges / of catastrophe’ (Alison Croggon), to ‘Prostaglandin spreads like cold honey / my cervix ripening, as an avocado in brown paper’ (Kathryn Lomer) to ‘The next pain / takes your spine apart. / Pelvis gags / some kind of thing with horns / in its throat’ (Rebecca Edwards), to ‘Out from you as if in a continuum / is she still yourself? Finally she is not / She separates calmly, not crying’ (Phyllis Perlstone), to ‘This is the first thing I want you to know. I am your mother and you arrived in me and from me. You arrived not “child as other” but as the child of my centre, the child of grass and orchards, of mulberries in summer’ (Jennifer Harrison) to ‘Early this morning, when workmen were switching on lights / in chilly kitchens, packing their lunch boxes / into their Gladstone bags, starting their utes in the cold / and driving down quiet streets under misty lamps, / my daughter bore a son’ (Margaret Scott), to ‘At Bindawalla, the hospital / where only Aboriginal babies were born, / the nurses laughed as they put me in a shoe-box / and gave me to my mother; she cried’ (Elizabeth Hodgson), and finally to Rosemary Dobson: ‘Eight times it flowered in the dark, / Eight times my hand reached out to break / That icy wreath to bear away / Its pointed flowers beneath my heart. / Sharp are the pains and long the way / Down, down into the depths of night / Where one goes for another’s sake’.

There is nothing wrong with this way of reading unless the reader imposes unwarranted generalisations rather than paying attention to the particularities of individual poems; to the way in which the same subject and similar experiences provoke such different responses and voices. Perhaps, though, just as profitably one can dip in and out of this collection reading each poem as poem and not worrying about its place in any sequence, jumping from, say, Jan Owen’s ‘We have no tender name / for you, small being, / drawn awry by some sad chance / as though you thought to play / too early with earth’s creatures, / fish, fowl, seal’ to J S Harry’s ‘I am mrs mothers’ day / I will hire myself out to you / for the 364 other days / I will not be satisfied by / 1 plus 364 / grottybunches of whitechrysanthemum / you choose to offer me snottynose’. Either way the reader will find lively poems which refuse to be shaped to fit any theory – one of the strengths of this anthology is that the editors, while elegantly shaping the collection, have not sought to impose boundaries.

Motherlode’s timeframe is restricted. The book concentrates on poems published between 1986 and 2008 and aims to be as representative as possible of the range of poets writing in that period. 1986 is chosen as the starting date because that was when the groundbreaking Penguin Book of Australian Women Poets was published and, although comparison is not intended, inevitably and valuably, Motherlode will allow readers to consider what changes and continuities they can detect over this period. Motherlode publishes a number of poets (Judith Wright, Gwen Harwood, Faye Zwicky, Judith Rodriguez, Margaret Scott, Oodgeroo Noonuccal, Bobbi Sykes and Rosemary Dobson among them), and a few poems, which appeared in the earlier anthology but it also gives space to newer and younger poets including Rebecca Edwards, Morgan Yasbincek, L K Holt, Petra White, Elizabeth Campbell, Jane Gibian, Esther Ottaway, Lisa Gorton, Judith Bishop and Francesca Haig. The editors say that, to make their selection, they read over 500 books of poetry (plus print and on-line journals). One of the excitements of this generous and generous-spirited anthology is to discover the number of Australian women poets writing now and the strength of their writing – from my own reading I’d hazard a guess that among the emerging generation of poets it is the women who are the most numerous and impressive. Opening the anthology with Gwen Harwood’s ‘Mother Who Gave Me Life’ and closing it with Judith Wright’s ‘Woman to Child’ provide powerful vantage points from which to view the achievement and consider the evolution of the tradition.

If Motherlode is a big book, Not A Muse, at over 500 pages, is huge. It features 114 poets from 24 countries. Ten of the poets (Pam Brown, Michelle Cahill, Suzanne Gervay, Margaret Grace, Tanya Hart, Jayne Fenton Keane, Laura Jean McKay, Kate Middleton, Leanne Murphy, Katrin Talbot) are Australian and, of these, only two, Pam Brown and Michelle Cahill, appear in Motherlode, and six were previously unknown to me. Perhaps the lack of crossover can be explained by the selection process – as I understand it the poets in Not A Muse were chosen by submission rather than by reading the available literature though, perhaps, some of the more well-known poets (Margaret Atwood, Sharon Olds, Erica Jong, Lorna Crozier, Laksmi Pamuntjak,) may have been invited to submit. This selection by submission does mean the quality of the poetry is a uneven and representation might be a little unbalanced but I don’t want that to sound like a serious criticism as I found much within these pages to enjoy and much that was new to me. The many countries represented allow for speculation about what might be thought universal and what culturally or personally specific.

Not A Muse is dedicated to ‘our mothers and sisters’. Its intent can be guessed by the politically and emotionally charged ‘sisters’ and it’s conceptual scope gauged by the sections into which it is divided. Each is conceived as an aspect of female identity, so each heading, bar the last, is preceded by the words ‘Woman as’: creator, family, archetype, explorer, myth maker, home maker, landscape, lover, freedom fighter, keeper of secrets, keeper of memories, ageing. It is tempting to read Not A Muse, more so than Motherlode, as a single, multi-voiced argument, as chapters in a developing thesis. The title is a rejection or a negative definition, specifically of Robert Graves’s conception of woman as poetic muse. The collection overtly celebrates woman as subject and agent, active, outspoken, central to the creation of her own life and the life of others. Here the section headings really do read like archetypes and could be said to be imposing limits on the conception ‘woman’. Can you imagine a collection with headings like: homemaker, housekeeper, spouse, companion or, indeed, muse?

This last question is not intended seriously. Poems on my imagined subjects do appear in the anthology and, indeed, ‘home maker’ is one of the headings. Individual poems in this anthology escape the confines of any characterisation even when they are at their most political and assertive and as I was reading I kept mentally thinking this poem could equally appear under this heading or that one. Try fitting the following excerpts under their assigned headings (answers appear, in order, at the end of the review):

Inside me, an Eastern European poet

is trying to get out. He’s killing me,

and I, with my recurring ear infections

and job, am slowly stifling him.

(Joan Hewitt)

I’m not getting up

when you call

I don’t want to

do your bidding

I’ll just lie here

chase some flies

with my eyes

You can be

forgiving

(Kavita Jindal)

Like a river feeding itself to the ocean,

Child, I continue to give myself to you

Until I become undone – scattered pockets

Of primitive earth, peeled bare.

(Tammy Ho Lai-Ming)

Because, like a poem, the city doesn’t know where our feet will

take us, we walked, unseeing, inaudible, heart-shaped. Too

many signs to follow. But there was a delight in being lost,

and rivering along took care of that until our voices

grew shrill and words

hung

in the air

(Laksmi Pamuntjak)

imagine your mother

down on her knees

and sucking cock

and understand you will never really know her

(Nicole Homer)

I have not swept the floor – the Amy of Now

must pass that task to the Amy of Tomorrow

along with folding the clothes

and taking the garbage out. Tomorrow’s Amy

may not mind, she might open the day

eager to eat chores with a fork

(Amy Maclennan)

The black of Radha’s hair is cow dung

and soot

Her arms of yellow

tumeric, pollen or perhaps

lime and the milk

of banyan leaves

(Nitoo Das)

One day she will put her hands out, fingers long

like yours

and she will

hold you

play you

and she will find the words that will turn you

into a cunt

(Sridala Swami)

A funnel has been shoved into my mouth

through which I am force-fed the sky.

I have eaten thunderheads, slaughtered angels.

And now they are mashing up the stars

into baby gruel.

‘You can eat anything,’ the doctors say

(Pascale Petit)

a Kurdish woman sang me a lullaby,

she said bab meant gate,

she said I know no poems

but I can sing to my dead child,

will you listen? And I think,

the whole world is listening,

you just don’t know it.

(Kirsten Rian)

I open my hand, see wrinkles, cold marks

of God’s anger upon my flesh. In these veins

runs depleted blood, returning capillary

by capillary from the centre of this rot.

Once, when I was a girl, I stood at the edge

of the sea and was tumbled over

by a rogue wave. What would it have been like

to glide on the undertow past kelp gardens

and coral reefs …

(Carol Dorf)

Who wants to hear about

two old farts getting it on

in the back seat of a buick,

in the garden shed among vermiculite,

in the kitchen where we should be drinking

ovaltine and saying no?

(Lorna Crozier)

The differences between women (writers) are as great as the similarities. The similarities between men and women (writers) are as great as the differences. The particular disproves any generalisation but generalisations persist. The strength of both these books, on social, political and artistic levels, is that they give voice to similarities and differences, to the particularity and generality of female experiences. These are poems by women from women’s perspectives about women’s experiences but they are not just for women. It would be a terrible failure of sensibility if a male reader were unable to imaginatively and enjoyably live within the poems in these two valuable collections. Both books belong in all public and educational libraries and would certainly augment a private collection.

(Answers: Creator, Family, Archetype, Explorer, Myth Maker, Home Maker, Landscape, Lover, Freedom Fighter, Keeper of Secrets, Keeper of Memories, Ageing.)