December 10, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

All My Goodbyes

by Mariana Dimópulos

translated by Alice Whitmore

ISBN : 9781925336412

Giramondo

Reviewed by Jeffrey Errington

In 1907 after living and writing in Europe since he was a young man, Henry James, aged a pinch below 60, sat down at his desk in New York and decided that that writing a novel was like looking through a self-made aperture of a “million-windowed” mansion. Inside was society’s dirty secrets and the position of the viewer glaring at these peccadillos was to frame its revelation. For Argentinian novelist and translator Mariana Dimópulos the house of fiction has become a rotting abode in a decrepit suburb. Not a stately Victorian home but a grotto; one flipped inside out to reveal yellowed bones grafted on as exoskeletons. Europe is stagnating. In All My Goodbyes, the main character’s (who remains unnamed for the entire novel) is listening to her boyfriend give:

“..extremely valid reasons (valid because they were his) why I should continue living in that den of European traditionalism, with its 500-year-old houses and its balconies dripping with flowers. He mentioned books, the peace and quiet, the university. If you found it hard to think, you could just head to the forest or to Italy, which served as something of a last resort for all melancholy Germans. The age of travelling the world and marvelling at other people’s poverty was over. And yet he still felt the weight of an entire continent on his shoulder” (p. 87).

She has no such weight and so moves like a leaf down a windswept strabe. She is the Antipodean answer to the centre, unweighted by its shifting traditions. Her character arrives in a Europe to find, disappointingly, that that culture has long been exhausted. She looks through the window, winces and chooses to voice no response, and moves right along.

All My Goodbyes is a short novel where the nameless main character wishes to escape Argentina to Europe. In the Continent she enters into a peripatetic existence, almost as if she were trapped in sleepwalking and returns to Argentina and then to the far south of Patagonia where she becomes embroiled in a brutal axe murder. Dimópulos’s touch-stone writer seems to be Thomas Bernhard and she has mastered and extended the Bernhardian mode: the controlled raving is accented and solidified by a non-linear ordering of the chronology, giving the structure a Cubist presentation. Her mastery is apparent as the reader is never confused as to where in the chronology the action is occurring. This structure relieves the characters of the burden of time as the Cubist narrative does not progress towards the final act (the killing of her lover and her lover’s mother) but the scenes are broken up and then grouped thematically. The structure of Dimópulos’ language supports the complexity of her protagonist’s crossing of European borders. A recognisable refrain in the syntax of the novel is heard when the final clause of a sentence or paragraph cancels out the truth that was asserted by its opening subject. The following examples illustrate this self-contradicting parataxis:

“They asked me for help and I told them there was no way I was going into the sea to rescue their horrible ball. That last bit is a lie. Nobody ever asked me anything” (p. 19).

“I could cross over to one side and say one thing and then cross over to the other side and believe the exact opposite.” (p. 31)

“It’s not true that we leave a place when the future is adorned with beautiful visions of faraway travels. We leave one morning, the morning after any given evening or the afternoon after any given midday, just when we’d decided to stay forever.” (p. 84).

“He removed his scarf, tied it around my next. We hugged and I promised him so many things: that I’d come back, that I loved him, all of them lies.” (p. 114).

One of the main character’s various jobs is at IKEA. Here she finds Europe in its purest form: sterile, easy to digest, useful and entirely supported by the labour of non-Europeans – a place where people go for the “narcotic” effects of a state of “pleasantness” (p. 42). It’s ironic that she is working here because IKEA represents the very thing that she wants to avoid – usefulness: “Being useful is of no use to me” (p. 14.) To deepen the irony, in a country where the language is not her own, she simply exists and language no longer serves a purpose. When she works in a German bakery she is frequently agitated as her German vocabulary is riddled with gaps, leading to misunderstanding between her and the boss, and the customers. This leads to her not knowing the German word for “jar” and her trying to break one in frustration but the jar rolls along the floor and still doesn’t break. So that “[a]t that moment, more than ever, I despise the Germans’ world-famous quality-assurance standards” (p. 91). Her constant movement is to avoid the pressure to perform a pejorative and menial task, which has been forced upon her both because of her Argentinian heritage and her gender. Without this language ability she comes across to all Germans as someone with no inner life. She pushes back as, “my tongue, as we all know, was still asleep in its Spanish dream” (pp. 62-63).

What she seems to be searching for is a community that is based on recognition. A place where the people recognise and accept her. Europe does not recognise her according to this logic. And she can not find it at home in Argentina either. In the wilds of Patagonia her identity exists in a state of perpetual flux as she is not even sure if she herself was not the one who used the axe to hack apart her lover Marco and Marco’s mother, Lady Dupin. Perhaps she is guilty, perhaps not. She certainly, like Ivan Karamazov, feels an ideological guilt for the crime that occured. Saying goodbye is her ideology, even if it means accommodating the death of her lover to render this scene impossible for her to re-enter, either in time or space. She accepts no responsibility for any one and she asks for none in return. She will never have the community that she longs for as she accepts that she has nothing in common with anyone else. She barely has anything in common with herself. She only accepts that her lover has become truly unknown when he can only become expressed in the past-tense:

“I never saw any of them again. I never spoke to any of them again, never replied to any of their messages. I put an end to them all, I didn’t leave a trace, didn’t feel a trace of remorse. There are all my crimes: all my goodbyes” (p. 140).

All My Goodbyes is an astonishing novel. It situates itself to the novel and to Europe with a level of sophistication that is, sometimes, lacking in Australian fiction. The translation of this novel by Giramondo contributes to the Australian literary ecosphere, and is to be celebrated. Particular mention must go to the translator, Alice Whitmore. Whitmore has successfully shepherded this novel from its Spanish language mode into an English language mode while maintaining the prose’s Spanish language strangeness. She does this by maintaining a near pitch-perfect tone throughout.

JEFFREY ERRINGTON recently finished his PhD in English at the University of Adelaide. He has previously been published in The Quarterly Conversation and Jacket Magazine.

November 23, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

Mosaics from the Map

Mosaics from the Map

by Robyn Rowland

ISBN: 978-1-907682-62-9

Doire Press

Reviewed by GEOFF PAGE

In 2015, Robyn Rowland published two books which seemed to be career-defining moments for her. They were the bilingual This Intimate War: Gallipoli/Chanakkale 1915 (originally with Five Island Press in Melbourne and now republished by Spinifex) and Line of Drift (with Doire Press in Galway). Between them they illustrated Rowland’s long and developing involvement with Ireland and Turkey as well as with her native Australia. Her new book, Mosaics from the Map, again from Doire Press in Galway, continues these themes and operates at the same high level of achievement.

It also reminds us of Rowland’s considerable and growing dexterity with the demands of the long poem and of poetic sequences. Both of the two 2015 books had several such poems and sequences and this one has even more. By “long” I mean poems of two or three pages plus, as opposed to half-page or one-page lyrics — or sonnets, for that matter. The risks of long poems, of course, are that they lose compression, one of poetry’s key ingredients, and can tend towards prose (even if written in strict metre). In Mosaics from the Map, Rowland has avoided these problems rather well.

There are several strategies by which she manages this, of which the most important are probably the depth of her research and her passionate identification with the subject matter. Her poems here are long because there is so much that the poet’s readers need to be aware of in order to have a sufficient comprehension of the issue.

Mosaics from the Map is divided into four sections: an introductory miscellany with several poems set in Turkey; a second biographical one focussed on the aviators Alcock and Brown; a third mainly set in Bosnia during the 1990s wars and a fourth with Australian and family references.

It may be instructive to look at one long poem from each section. The first we encounter is “Titanic — A Very Modern Story”. It’s made up of nine long-line stanzas re-telling the now well-known story of the famous 1912 shipwreck. It begins with an epigraph from a survivor, Jack B. Thayer, who surmised that “the world of today awoke April 15th, 1912.”

Rowland cleverly begins every stanza with a short word or phrase to illustrate this modernity — and to emphasise all the elements of the story which have kept it relevant. “It has heroics,” she begins and goes on to talk of the radio operator, Jack Phillips, “in the Marconi wireless room /without windows” who “kept sending signals in perfect Morse”.

“It’s ‘local’,” Rowland continues in stanza two and talks about the Irish element in the story, particularly a survivor’s marriage “smothered in a deathly hush”, a husband now “shamed for his survival, /yet he’d seen so many off safe and who wouldn’t jump for a boat?”

Rowland continues in this way in subsequent stanzas covering the international dimension to the story, the role of coincidence, the role of greed in the taking of excessive risks, the sheer incompetence (“no binoculars in the crows’ nest so only fifty seconds between spotting the berg and hitting it”), the weather of the night itself (“sky jammed tight with an excess of stars”), the immediate aftermath (the rescue ship, the “Carpathian”, “a ship of widows”) and the longer-term, rather trivialising aftermath (the heroic band-leaders’ violin selling in 2013 for “one million pounds”).

Rowland’s metre, an important part of the poem, is somewhere between iambic or trochaic hexameter and free verse, an intriguing decision which risks clumsiness but in fact maintains a kind of continuity while keeping the reader’s ear guessing.

The whole poem is clearly “documentary” in intent, e.g. the facts in the Carpathia’s “loading 710 left alive from the 2200 who boarded”, and yet it’s also shot through with lyrically descriptive, if disturbing, passages such as: “The dead clustered in their / white lifebelts like flapping seagull wings in the lapping waves”. The Titanic story has been often told, usually in prose and at much greater length, but Rowland has made the event even more poignant, while at the same time somehow foreshadowing the wastage that was to occur in the conflict about to begin just over two years later.

Mosaic’s second section, “Sky Gladiatorials” is a sequence of six poems about the careers of the aviators Captain John Alcock and Lieutenant Arthur Whitten Brown who made their reputation in World War I and then became the first to fly across the Atlantic non-stop in 1919.

The sequence starts, characteristically for Rowland who is always keen to look beyond the “received” imperial account of events, with her poem, “The Other Side of Things”. It begins from Alcock’s point of view in 1917 as he flies over Constantinople, “A city lovely in both poetry and Churchill’s dreams …” The rest is from the viewpoint of the nine-year old Turkish boy, Irfan Orga, who looks up to see “three planes appear. / He never saw such a thing, wings and whirring. He wishes / he could fly.” Then we are shown the “cartloads of lolling heads, limbs akimbo, disconnected flailing stumps and the surprised wounded …” The poem ends with a resonant couplet: “This was the first bomb. They meant to hit the war office but the bombs went wide, a man said. No-one believed him.”

The next poem in the sequence, “High, Higher: Alcock” begins again from Alcock’s point of view above the “mat of minarets / and domes” and goes on to describe the rest of his and Brown’s war experience, “knowing we made a difference, new gladiators of the sky. /We’ll win. This war will end all wars. Never again.” The irony is more than a little touching.

The third poem, “Dead Reckoning: Brown” is from Brown’s point of view above the Atlantic in 1919 and looks back over the terrors and hardships of the war, including “Fourteen months in a German camp in Claustal”. Lines like this may not sound poetic in themselves but in context they work perfectly well. It is one of Rowland’s persistent achievements that she can manage such combinations of the flat and the lyrical.

The last two poems in the sequence are concerned with Brown’s continuing PTSD (though the poet doesn’t call it that), especially during World War II in which his son, Lieutenant “Buster” Whitten-Brown was shot down on June 5/6, 1944.

Part three of Mosaics from the Map consists entirely of “War. What is it Good For?”, a nine-poem sequence set in mainly in Sarajevo in the wars of the 1990s. It emphasises the pointlessness of the conflict, the internal opposition in Belgrade to the war and its unrelenting savagery. The sequence is varied and hard to summarise but its tone and texture can be sampled perhaps with a few lines from the viewpoint of a woman in Sarajevo after the widely-reported bread queue massacre on May 27, 1992. “The knee is smooth, lovely in its meniscus-shaped curve, / thigh pale from lack of sunshine close to the torso, / and the foot, its cardboard tag, five toes pointing towards / the sun, surprised almost, caught off guard.”

It is this kind of evocative detail which takes Rowland’s apparently “political” poetry well beyond the limitations of partisanship. Although her long lines often have a rhetorical feel they are far removed from the self-interested rhetoric of the third-rate politicians who bring such damage about.

The final section of Mosaics from the Map is dominated by the sequence, “Touchstones”, in which Rowland re-creates the lives of some of her Irish ancestors, particularly her great great-grandmother, Annie Harding Lambert (1880- 1957), and the successive ravages inflicted on them by scarlet fever or scarlatina, as it was sometimes called. It’s an extended familial tribute that quite a few Australian poets (including this reviewer) have felt compelled to make over the years. And it’s always interesting to see where the emphasis is put, which maternal or paternal line is traced back and which ignored or deferred.

The “Touchstones” sequence begins with “Family Catalogue August 1880” which delineates the social and political context in Ireland when Annie was born. Several of the subsequent poems are written in the voice of Annie. The eighth poem is in the voice of her son, John, and remembers that his mother “preferred being close to a harbour, a beach, / or a river. Said her soul always rested near moving water. // On her papers they call her settler. But she never was.”

Rowland’s admiration for her great great-grandmother — and the resilience she embodied — is clear and the poet’s sustained portrait of her times more than convincing.

Significantly, in the sequence’s ninth poem, “Postscript”, Rowland makes her divided feelings for Ireland and Australia quite explicit: “I am everywhere and nowhere, longing pulses / inside the green whispering in my blood. Belonging, exile — the seesaw. / That word home — it draws itself out like a skewer.”

GEOFF PAGE is an award-winning poet and critic. His most recent collection is Hard Horizons, 2017. He edited The Best Australian Poems (2014 and 2015)

November 16, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

No Country Woman: A Memoir of Not Belonging

No Country Woman: A Memoir of Not Belonging

By Zoya Patel

Hachette

ISBN: 978 0 7336 4006 3

Reviewed by TAMARA LAZAROFF

Zoya Patel’s No Country Woman: A Memoir of Not Belonging is a collection of twelve memoir essays that explore the experience of growing up as a migrant and person of colour in Australia – in particular, negotiating the tangle of hyphens which Patel inhabits as a female Indian-Fijian-Australian. In the work, then, Patel examines identity, race and gender, from a personal standpoint. For example:

‘If anything, I have spent my life trying not to feel Fijian-Indian, desperate to prove that my cultural identity is as ‘Australian’ as that of my white friends who grew up in the same white suburbs as me, attending the same schools…’ (41).

However, she always has one eye on the broader social forces at work that have shaped her experiences and desires. Patel describes how during her childhood in the ‘90s, when Pauline Hanson’s insistent message that immigrants should ‘go back to where they came from’ was rampant across the news, she feared that the authorities would come to take her and her family away from their new Australian home (47). Similarly, Patel also reminds us that it wasn’t until 2011 that Neighbours featured its first non-white family, the Kapoors, on Ramsay Street after almost thirty years running; and that the decision was met with such opposition from Australian fans that it attracted international media attention (59). Soon after, the Kapoors were sent back ‘to where they came from’ – to India – to visit a sick relative and never returned.

In No Country Woman, there are numerous physical journeys recounted – back, to, away from, around, through – though there are never any convenient disappearances from the screen, map or storyline. Rather, the experiences of movement are thoroughly picked apart.

There is the story of Patel’s family’s migration from Fiji to the NSW town of Albury where Patel and her three siblings are teased, to put it mildly, for having skin ‘…brown like poo’ (93). There is a family ‘roots tour’ holiday to Patel’s paternal great-grandmother’s village in Gujarat where eleven-year-old Patel is first confronted with ‘meeting people not that different to me living in much worse circumstances’ (147), and the learning that this distress has a name: migrant guilt. There are also interstate day-trips to purchase salwar kameez in the Indian streets of Western Sydney’s Liverpool that elicit a different kind of shame, and encapsulate the ‘unspoken conflict between the two halves of my self’ (52); teenaged Patel trails behind her chirping mother and sisters unable to fully participate in their merriment.

Patel chooses, however, to begin the collection, in the title essay ‘No-country woman’, by detailing her first trip back to Fiji after many years absence as a twenty-eight-year-old adult. Uncomfortably, she travels with a tourist party and her white male partner, in order to attend a wedding at a ‘paradise island’ resort. The only non-white person, other than the kaiviti staff dressed in grass skirts, she feels as much a sense of injustice as she did in India. Afterwards, when she and her white partner – a union considered scandalous in South Asian cultures (12) – spend some time in Nadi, Fiji’s capital, Patel is challenged about her Fijian-Indianness by a local she meets on the street. She comes to realise that she doesn’t belong there in Fiji, either – and here lies the premise of the book. Patel is a no-country woman, always asking herself the question (and fielding the same from others): Where do I really come from? Where is my place? How and where do I fit?

In the essay ‘Money Can’t Buy Harmony’, another particularly poignant physical journey – a tragicomedy, in fact – Patel is shown exactly. A Canberran teenaged schoolgirl, she is invited to participate in a well-intentioned but not particularly well-thought-out government-funded bus tour with other teenaged people of colour. Across rural NSW they travel performing traditional dances and/or showcasing their other talents – Patel gives a speech – for umpteen school assemblies. Their purpose: to spread the message of cultural harmony and eradicate racism at its root – in the country’s youth, apparently. But, what the organisers did not consider, Patel writes, is that the reasons for some rural communities’ us-and-them attitudes may not have been simply due to misinformation or ignorance, but lack of opportunity in tight economies, ‘poverty, isolation… and [lack of] representations of diversity in the media’ (74). No amount of singing, dancing or orating was going to change that. Patel remembers vividly, during one of the Harmony Ambassadors’ performances, there was a single Vietnamese-Australian boy, in a sea of bored faces, ‘…who visibly shrank down in his seat, as if he wanted to make clear that he wasn’t associated with this ragtag mob of weirdos who all happened to be not “Aussie” (72).’

Another ‘journey’, or trajectory, examined in No Country Woman, and perhaps one of the most important, is Patel’s engagement with feminism – as a migrant and person of colour. Many readers will know that Patel is the also the founding editor of the online feminist literature and arts journal, Feminartsy, and was previously the editor of Lip Magazine, another Australia-based feminist publication – these passages are detailed in the book. Patel’s dedication to and exploration of feminism has been lengthy. But for a teenaged Patel growing frustrated with the gender norms within the Fijian-Indian community – ‘the parts…that made me feel that perhaps women weren’t valued as highly… as in my immediate family’ (82) – there didn’t seem to be much in the way of easily accessible literature to help her navigate the terrain in a way that fit with her day-to-day realities. Most of it was ‘…targeted at middle-class white women’ (214). The concept of raunch feminism, for example, felt alienating; Patel writes: ‘…I was still trying to determine whether my body was mine to dress in jeans and a normal t-shirt that didn’t entirely cover my bum’ (215).

On the flip-side, Patel reasons that for the Fijian-Indian community in Australia, like many migrant communities, the wellbeing of the group is ‘…considered more important than individual freedom’ (105) – and is a valuable position, too. Patel is at pains to add that she doesn’t want people to think talking about issues of gender inequality in Indian culture means that she favours Australian culture or sees it as progressive or culturally superior (209) – ‘Women in the West are certainly less visibly confined by gender norms, but the patriarchy is insidious, and it’s usually what you can’t see that you should be paying attention to’ (208). Rather, in No Woman Country, Patel wants to open up and make space for healthy discussion about intersectionality, the valid variances in the lived experiences of all women and feminists.

Certainly, conversation with friends – ‘almost exclusively with women…’ (116) – and years of mulling over cultural identity issues together have been imperative to the writing of and thinking through the ideas in No Country Woman (261). In perhaps one of the most moving essays in the book, ‘Kindred Spirits’, Patel traces one particularly influential female friendship from the first year of high school to the present day. Patel writes that she and Melissa, who happens to be white, ‘graduated from one obsession to another’ (97) – from ‘… horses and Harry Potter… to zines, writing… indie rock music, manga… vegetarianism, animal welfare, backpacking through Europe and, most recently, dog memes’ (97). In the spirit of mutual generosity and support, as young women they dared to dream about their future selves and careers. In fact, in year nine they both completed a week of work experience at Lip; the year was 2004 and it was a time when there was ‘…nothing more lame than feminism (100).’ Still, Patel writes that Melissa was ‘the person who, in some ways, introduced me to myself’ (97), and to an identity that saw past ‘notions of race, or gender, or purpose (116).’ Patel goes on: ‘Together, we bridged a divide that had been constructed from centuries of racial prejudice that assumed our skin colour made us so fundamentally different that our friendship would taint both of us (116)’.

No Country Woman reads as though a friend is sharing some of the most important and intimate things about her life. Thoughtful, well-researched, straightforward and often funny, the book sits closely in ‘friendship’ to other contemporary books such as Maxine Beneba Clarke’s The Hate Race, Alice Pung’s Unpolished Gem and Durga Chew-Bose’s Too Much and Not The Mood. The collection will appeal to a wide audience, including first, second and even third generation migrants, as well as those interested in the subjects of race, identity and intersectional feminism in contemporary Australian culture.

TAMARA LAZAROFF is a Brisbane-based writer of short fiction and creative nonfiction. She has a particular interest in hidden histories, the migrant experience, feminist and queer themes, oral storytelling traditions and celebratory stories of social interconnectedness.

November 10, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

Dark Matters

Dark Matters

by Susan Hawthorne

Spinifex

ISBN: 9781925581089

Reviewed by MEL O’CONNOR

In counterpoint to how these histories have been silenced and extinguished, Susan Hawthorne, in Dark Matters, testifies to the horrifying reality of abduction and torture of lesbians—especially outspoken activist lesbians, such as Kate, the central character of the text.

This is not a quiet novel, of implications and subtlety: it is designed to upset, as human rights have been historically upset by happenings such as these. Kate is stolen from her home by men who brutalise her, in particular by attempting to ‘convert’ her to heterosexuality. Only after Kate’s death are her fragmented writings and journals from the time of her incarceration discovered by her niece, Desi, who attempts to organise and interpret them for a university research project. Dark Matters as a work lies somewhere between the research project Desi creates, and a charter of Desi’s reflections on Kate’s experiences.

Of the many notable features of Dark Matters, Hawthorne’s style is perhaps the most immediate: from her lack of descriptors on dialogue to the visceral empathy she evokes in her practised prose-poetic voice, her expertise is ever-present. In some ways, the text wars between genres—prose poetry, horror, and speculative fiction all have elements present—but it is poetry that the work most resounds with. Hawthorne employs recurrent symbols, and recalls found artefact poems, such as poetry in lines running back and forth (p5), stream-of-consciousness rhapsodising (p13), and free associative Latin, where the language runs as rampant as the wolf Kate envisions herself as. In step with prose poetry, the use of space is deliberately selective; Dark Matters swims, framing fragments as verse. When Kate’s poetry—or Desi’s found artefacts—occupy the work, they dance down the page (p29):

dance dance dance

dance the trata in your

red white and black garb

dive down dive down

dive underground

dance dance dance

dance the trata

for bread and pomegranate

dance as we have

for millennia

as is carved

on the tomb

` of the dancing women

dance a zigzag

dance the weave of a basket

dance the stars and spirals

inwards

outwards

The writing is alive and evocative—a distinctly lesbian call to motion in the style of prose poetry.

Further supporting a prose poetic angle, Hawthorne’s leitmotifs are hypnotising, not least of them the character of Mercedes. Kate’s lover before she was abducted, Mercedes’s perspective bookends the work, and indeed, she is a beacon throughout the text—“I will fill my mind with Mercedes” (p18), writes Kate, her “Querida Mercedes” (p37)—an icon of desire and desperation from page to page. This memory-Mercedes secures Kate to her identity, even throughout her torture, because Mercedes is concrete proof of Kate’s identity as a lesbian—something her abductors are desperate to erase and destroy.

Another leitmotif is the figure of the eagle. Tellingly, it is from Mercedes’s point of view that this creature is first seen—“My eagle swoops into view” (p1)—but it is Kate who recalls this eagle in her trauma, imagining her “arms growing wings. Wings of heavy metal … Too frail to fly” (p17). Throughout her incarceration, Kate grapples for symbols such as this, coding them into her being. This is her means to survive amidst the nightmare of her life (p50):

Aaaagh. I vomit. I shake./I shake and I sprout feathers. I take off and soar: a wedge-tailed eagle. I leave this horror behind.

There is a visceral empathy embedded deep in this, as there is through all of the work. Usually, it stems from Desi’s ignorance as a narrator. When Desi writes “This page fell out and I can’t figure out where it goes” (p114), or “I wish Kate had been a Virgo because then I’d have some chance of following her schema” (p20), it is heartbreaking—Kate is literally silenced by Desi’s lack of knowledge or understanding, symbolic of how lesbians throughout history have been silenced by a lack of knowledge or understanding on a much larger scale. But here in particular, the empathy for Kate is born out of a sense of injustice to her situation, and a sympathy to her desperate wish for escapism.

The eagle resounds both forward and behind in the text, tethered to Kate’s “Codex psapphistra” (p148): Desi writes, “She describes a range of animals from a lesbian-centric point of view. She is creating a universe in which lesbian symbols lie at the centre” (p148). Kate—by her Greek name, Ekaterina—moors herself to her Greek history. Because of this, Dark Matters bleeds with heavy Greek interplay. Kate’s obsession with the Muses and with Psappha may unmoor a reader not well-versed in this history. However, as Kate is herself unmoored, this decision is deliberate; the impact is viscerally sympathetic, rather than alienating.

Similarly, Kate, her physical and emotional boundaries under assault, wars between ‘micro’ and ‘macro’ attitudes to her situation—the micro, an intrinsic desperation for herself alone, and the macro, a selfless agony for the thousands of lesbians like her. On a personal level, she writes: “There I am, still strapped in, covered by their hate. I cry and cry” (p51)—on a societal level, she writes: “I cry. I cry for all. For all the women. For all the lesbians” (p52). For Kate, this is another means of survival—she reminds herself of the bigger picture in order to stay strong and silent, refusing to give information to her abductors, knowing how much is at stake. She is painfully aware of how much her incarceration represents (pp109-112):

The boundaries between my flesh and theirs. They have violated those boundaries. They have violated me. And through me, as they know, they are symbolically violating every other lesbian on this planet … Lines of self. Lines of the other. They rip through the lines.

Inevitably, little by little, her resolve crumbles, her psyche under attack by these invasions. Lines relating to her torture, for example, that her captors “Took [her] hands and strapped [her] to the … I cannot call it a bed” (p47, author’s ellipses), are later matched by lines recalling her time in Greece before she was incarcerated, such as “for this narrow space could not be called a bed” (p59). This second line is provided as Kate settles down with a foreign paramour. The striking similarities in expression and language between these quotes evidence how the horrors of Kate’s incarceration have contaminated her memory. The reader sees her trauma, achingly, begin to corrupt her experience of significant lesbian encounters through life, buckling her sense of lesbian identity.

To match how the boundaries of Kate’s identity are compromised and attacked, her sense of self unmoored, Hawthorne provides a ‘shredded’ story. Desi struggles to piece together the narrative—“What we have left are fragments” (p3); “It’s a giant jigsaw” (p35)—just as Kate struggles to piece together a psychic defence—“I forget who I was, who I might have been” (p169); “I have died and died and died” (p173). This wounded sense of self and community is what makes the work so unforgettable.

In a rare moment of awareness from Desi, she writes: “Dark matter is almost imperceptible. Invisible and yet it takes up space. Like a lesbian in a room full of people” (p160). Hawthorne depicts a lesbian under siege, her personhood, psychic, and personal boundaries all compromised by systems which cannot accept her. Personally, she is attacked by abduction and assault. Societally, she is diminished through prejudice and inequality. The resulting text is something profoundly important. Dark Matters is a war-cry. It is a declaration of personhood and reclamation of identity from the traumas induced by these dark histories.

MEL O’CONNOR is a Professional and Creative Writing graduate from Deakin University. Her experience is in communications and administration. She is working on her novella, a literary fiction about the animal rights scene.

November 7, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

Light Borrowers: UTS Writers’ Anthology 2018

Light Borrowers: UTS Writers’ Anthology 2018

Foreword by Isabelle Li

Brio Books

ISBN: 9781925589627

Review by BEEJAY SILCOX

“In the beginning, it was just us and the words,” writes University of Technology Sydney (UTS) student –and writer – EM Tasker. “We sang them into being, and they existed only in our minds. They reproduced by passing from the lips of one person to the ears of another. But that meant they could only reproduce when people gathered. That was until Writing joined the relationship. The resulting ménage à trois was wildly successful.” (171)

For 32 years, UTS has been celebrating the fruits of that lexical love triangle by publishing an anthology of work penned by its Creative Writing students. This year’s lovingly-assembled edition, Light Borrowers, borrows its title from Sylvia Plath’s poem ‘The Rival’, and with it the tension ever-present in Plath’s poetry – the glorious tension between beauty and annihilation.

As a reader, opening an anthology is akin to entering a room of strangers; we arrive hopeful but nervous, ears pricked for conversation, camaraderie and conflict. How (and how well) we are welcomed is largely dependent on our hosts, on how well we are introduced to the crowd. In Light Borrowers, UTS alumna, author and translator Isabelle Li greets us warmly at the door with the key to a live and lively room. There is one line, she argues in her foreword, that will unlock the anthology; it is waiting for us near its midpoint, in a poem by Shoshana Gottlieb: “The In Between / pockets of time that happen as we wait for / the moments we beg to define us.” (163)

Light Borrowers is anchored in this ‘In Between’. Across a range of genres, from memoir to flash (one of its most memorable contributions by Qing Ming Je is a single, knife-edged sentence), each of its 28 pieces inhabit the liminal spaces that separate, connect and define us. Between childhood and adulthood; believing and knowing; memory and forgetting; remembered pasts and imagined futures; fable and fact. Between, as Gottlieb describes, “the Things We Do and the Things That Happen To Us.” (164)

In Sydney Khoo’s ‘I’m (Not) Lovin’ It’ we slip between the sheets, as they wrestle with sexual labels and expectations that simply do not fit: “Wearing those labels felt like sleeping in a bed that wasn’t mine,” they write. “As comfortable as the mattress was, and as clean as the sheets were, I woke up irritable, unrested.”(38) Khoo’s piece is a confident love story – a self-love story – which begins when they ingeniously convince their conservative mother to buy them a sex toy.

In Sally Breen’s ‘The Garden’ we slip between the senses to let “vivid colours draw vivid memories.” In it, a woman remembers versions of her grandfather’s garden and the versions of herself that wandered it. It’s a piece heady with synesthetic nostalgia, brilliantly coloured in “Kodachrome hues”:

“And all that remains is this orchard. Heirloom apples, small and crisp. I twist an apple, a revolution. And when it snaps the branch flicks back. Fruit fits snugly in my hand. It is this orchard that my grandmother adored. Blue Mountains. These blue days of sadness.” (28)

And in Amy Shapiro’s ‘Scheherazade’ we slip between forms as she takes the cage of a theatre script and shakes the bars to produce something else entirely – a dark vision of a mechanised future that explores that unfathomable space between consciousness and algorithm. “Suffering isn’t regression,” (55) Shapiro’s human protagonist tells her android interrogator. How might he believe her?

But it is the space between worlds – the space between cultures, traditions, histories and geographies – that beckons most insistently in Light Borrowers. “My people are the invisible fatalities / The footnotes of / Your people’s / History,” (209) laments Christine Afoa, of her Samoan heritage in ‘My People’ – a poem fearless, furious and proud.

“There is no X to mark my spot on this land,” writes Kiwi Shana Chandra, as she grapples with how conspicuously inconspicuous she feels visiting India:

“I know that if I enter this crowd, its surge will envelop me and I will be undetectable. I remember how scared I was at this thought when I first got off the plane in India, annoyed at all the brown faces, identical to mine. I am so comfortable wearing my difference in New Zealand and Australia that here I feel different, although I look the same as everyone else.” (190)

Worlds erased and escaped, lost and left, conjured and confining – Light Borrowers is anchored in the sensory details that bring worlds to life: the slow, night-time clacking of a basket of live snails; a lipstick kiss on a pillowslip; a sweaty city of “sleep deprived malcontents wearing badly fitting underpants”; a witty graffiti retort. “They zoom past the train line,” writes Jack Cameron Stanton, “and he sees the famous scrawl: GOD HATES HOMMOS, in black spray paint, with a neater, more curvaceous response spread beneath it in purple: BUT DOES HE LIKE TABOULI?” (83)

Those worlds are as individual as their authors; “inconsolably human” to borrow a phrase from Stanton. The triumph of Light Borrowers is that it has been constructed in, by and for, a diverse Australia, and it shows. This is an anthology that cares about the differences within Asian-Australian communities, not just between them. As Khoo writes: “Growing up as a second-generation Chinese Australian, I was constantly learning that the norm was actually just my norm.” (35) We are all living in our own, individual between place, Light Borrowers argues. Between the people we are, and the people we wish to be. Between ourselves and the world.

And yes, Light Borrowers is student work – the product of exuberance, ambition, earnestness and generosity. Every piece carrying the coiled energy of a seed, the shape of the author to come.

When people write of writing talent, there’s a tendency to equate youth with promise. We make list after list of bright young things to watch, and use ‘young’ as a synonym for ‘new’. Light Borrowers offers a magnificent rejoinder in the work of Echo Qin He, a woman determined to escape her inheritance of silence:

“I am in my 50s now. I don’t want to regret on my deathbed that I never gave it a go. It has taken me a long time. I have begun writing and my muscles are getting stronger day by day. Elements that used to be hard previously, that I didn’t know how to write about, now come more easily.” (160)

As a new migrant to Australia, writing – even reading – fiction felt like a luxury Echo Qin He could not afford, “making a living had to come first”. We can’t afford to lose or alienate voices like hers; new, urgent and carrying a lifetime – generations – of untold stories. We need more spaces like the UTS anthology, spaces that make room for new writers as they navigate that vital exploratory, playful space between searching for, and finding, their voice. A place where they can borrow a little light.

BEEJAY SILCOX came to writing circuitously; after narrowly escaping a life in the law, she has worked as a criminologist, agony-aunt, strategic policy boffin, and teacher of Americans. It is better for everyone that she now works on her own, as a literary critic and cultural commentator. Her award-winning short fiction has been published internationally, and recently anthologized in Best Australian Stories and Meanjin A-Z: Fine fiction 1980 to now. Incurably peripatetic, Beejay is currently based in Cairo, where she writes from a century-old building in the middle of an island, in the middle of the Nile.

September 21, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

Renga: 100 Poems

Renga: 100 Poems

by John Kinsella and Paul Kane

GloriaSMH

Reviewed by SIOBHAN HODGE

Renga: 100 Poems is a collection over ten years in the making. Paul Kane and John Kinsella, writing in exchange via the Japanese renga form, have compiled a long-running poetic dialogue – unlike traditional renga, each poem is individually written and a response then followed by the other poet. In his foreword, Kane states:

We each had a long history with the other’s country and we both wrote out of a sense of being firmly placed in our respective locales. Moreover, many of our interests coincided, particularly in aesthetic and environmental concerns. Why not continue an hour’s conversation over an extended period – and in verse? (iv)

Despite this light-hearted opening, consistently at the forefront of these exchanges is a deep concern for the environment, documenting anxieties and innate senses of responsibility to the world. For example, one pair features a biting criticism of mining in Pennsylvania and Western Australia:

Atop one ridge in

central Pennsylvania

geologic waves

roll steeply, starkly away.

Coal country, that first black gold.

Miners digging graves.

Here, not meth but methane kills,

as an oil rig.

Hard country, anthracite black,

with pastel clouds, slate blue sky… (Kane, “Renga 27”)

Kinsella’s reply situates similar concerns in Western Australia:

There’s a fair chance

that one of our neighbours

is furtively mining away

the valley wall: the scraping

and hammering, back and forth

of a front-end loader. His trucks

that weigh heavy on axles,

frequent departures.

…When the valley wall gives

way, the shockwaves will spread

for acres. We’ll all hear The Fall.

But hearing is selective still:

what we hear to the point of pain

others cancel out with paeans

of praise. Who’d refuse God

in God’s own country? (Kinsella, “Renga 28”)

For both poets, the collection is a means of consolidating frustrations regarding destruction of the natural world, but the text is not exclusively eco-critical. Rather, this is an organic discussion – political and philosophical – in a revised form of epistolary poetics. This is also a collection preoccupied (in the most playful sense of the word) with the many meanings of “home”. The poetic dialogue, labelled a contribution to the pastoral eclogue genre by Chris Wallace-Crabbe in his blurb for the book, Kane and Kinsella engage in a rhythmic dialogue that doesn’t stray far from the importance of situatedness in the natural and human-impacted world. In “Renga 3”, Kane introduces some of these ruminations:

So the poet asks

“Where do we find ourselves?” as

if seeking a place

of knowing could conjugate

“to be.” I am is future

tense when now recedes.

Yet think of the paperbarks

along the Murray

wetlands, how they need an ebb

in spring floods to grow young trees:

alternation rules.

That’s why now is moment by

moment, and why I

find myself in your country

each year, like a second home.

By the time the collection reaches “Renga 78”, notions of home have become saturated, as shown in Kinsella’s response:

Homecoming homebound homebody homebred.

Homeland homemaker homeomorphic homeless.

Homebuilt homeowner homesteader homeostatic.

Homeschooled homework homer homeland.

Homespun homemade homebrewed homeopathic.

Whatever the case, the changing light.

Whatever the case, homewardbound.

Each poem is a means of traversing geographic and philosophical distance, but connection is also multi-faceted, growing and evolving, and linked with the speakers’ abilities to traverse these spaces. Experiences of others, including Aboriginal people, are highlighted but not co-opted. Renga is an accumulation of acknowledgements of outrages – against people and the environment – accompanied by ruminations on the personal experiences of both poets, but the focus is primarily on the voices and experiences of the poets themselves. Within these layers of observation neither thought nor experience are being colonised. This is a deeply critical collection, concerned with the impacts of pollution, environmental destruction and decay.

Why select the renga form for a collection of this nature? There is no detailed discussion of why this traditional collaborative Japanese poetic form has been selected, beyond Kane’s definition: “a single entity built by accretion, like limestone, and a virtual fossil record of the multiple procedures used to construct it” (a more comprehensive and generous assessment of the form than his earlier description of it as “the little brute”!) (vi). Renga are constructed by several poets working together. Kane adheres more firmly to the form than Kinsella, who splices in a lyrical approach. Stanzas are traditionally written by alternating poets, inspired by the one preceding, but Kane and Kinsella opt instead to present individual, entire renga. A discussion of motivations for this style of adaptation, as well as poems that reflected on the impact of the renga on their dialogue and the environments they discuss, would have been welcome, particularly in this collection’s depictions of emblems of colonialism and environmental exploitation. The decision to select a traditional Japanese poetic form is situated firmly in the opportunities offered by the form, regrettably missed is the opportunity to open discussion of the historical and cultural significances of the form itself, as well as the opportunity to reflect on the implications of this act of cross-cultural world literature, a contribution which would have well suited the thematic focus of the collection. Timothy Clark observes that:

In Japan, a renga was a collective poem written according to a great number of apparently arbitrary rules, which each participant adopted from his predecessor… Renga is not primarily a poem or a theory of poetry, neither is it quite criticism; it is a situation, an experiment with the nature of poetry and language (32).

Clark surmises that the poetic form is an incorporation of Buddhist conceptions of the dissolution of the ego, reflected in “the subversion that Renga brings to any thought of property in relation to a poet’s voice” (33). However, in Renga: 100 Poems, the author of each piece is acknowledged via initials in each piece’s title. There is no subsuming of authorial agency or identity, despite what the traditional form would typically entail.

For a collection preoccupied with communicating over distance, acknowledging room for empathy without complete mirroring of experience, the renga is an ideal means of conveyance, but the form gives room to both what can and cannot be shared. In “Renga 61-67” Kane and Kinsella highlight on-going issues of Aboriginal disenfranchisement in Australia, both poets employing a series of black-white binaries deeply critical of colonialism’s “…roll call / of slavery and land claims” (Renga 66, Kinsella). However, there are no directly Aboriginal voices in this collection; Kane and Kinsella acknowledge but cannot speak for these experiences. Rather, this is a vital discussion saved for another 2018 publication, False Claims of Colonial Thieves, a superb poetic treatise and dialogue between Charmaine Papertalk-Green and John Kinsella. In Renga, Kane and Kinsella echo an earlier non-Japanese interpretation of the renga as a form that constructs layers of tension and selves, demonstrated in the 1971 collection Renga: A Chain of Poems, a multi-lingual exercise by Octazio Paz, Edoardo Sanguineti, Charles Tomlinson and Jacques Roubaud. In this renga collection, Paz, Sanguineti, Tomlinson and Rombaud presented “multiple voices, multiple selves”, embodying Paz’s notion of “the transient, unstable, relativistic self” (Starrs, 280). Despite adhering to the conventions of the collective, communal form, both texts do not render authors’ voices anonymous. Unlike the 1971 Renga however, Kane and Kinsella’s Renga moves to thematically bridge gaps, rather than emphasise them, while also strictly avoiding any appropriation of voice.

Kane and Kinsella’s poetic responses conversationally engage with the preceding piece before taking the introduced theme in a new direction. Among the shared concerns are mortality, environmental destruction, war, shifting between and intricately connecting the personal, political and philosophical. One recurring image is fire, as in Paul Kane’s “Renga 49”:

For two days we lived

in a stinging haze of smoke

as the Gippsland fires

far away burned beyond reach.

Smoke puts everyone on edge.

The plan: fight or flight? –

that atavistic question.

The Ararat fires

ended on our mountain,

the one house given to flames.

Our Warwick neighbor,

Burning off the adjacent

field one autumn, lost

control of the blaze in wind:

we were blackened fighting it.

In Victoria,

it’s different: fire is fiercer,

and we’d likely flee.

A house I can rebuild, but

a life? I want my own death.

And yet, we’ve ceded

so much to indifferency,

slowly poisoning

our world – no, the world – ourselves,

blackening the days ahead.

Wounded in his den,

the baited badger will kill

a dog. The snarling,

the cries, are all we’ll hear when

we, in turn, are run to ground.

Kinsella’s “Renga 50” compounds anecdotes, voices and shared experiences, coupled with grim warning. For both poets, the role of preserving place is a constant and communal threat:

The restart of the fire season:

a mushroom cloud on the first

horizon – the penultimate –

an edge not far enough for

comfort. From his fire-tower

my great-grandfather scanned

the sea of trees for that wisp:

that leader, sign you can never

over-read. I went there

as a child and did the same.

I barely remember. Maybe

he was already dead. I’ve been

talking fire all day long: poets

writing it, neighbours discussing

the risks, all our preparedness.

The firebreaks are done.

Scraped and scraped again,

looking for that second layer,

that second safer layer.

It never reveals itself.

Mostly, it’s the smell: weird

Signs of noses cocked to the air,

like some unwholesome fetish.

It’s so dry that ‘dust to dust’

would seem our mantra.

But it’s not. ‘Fire to fire’,

‘fire to fire’ is all we utter

when the water-tanks are low

and flood (should we be smitten)

could only fill the valley

enough to lap at the foot

of our place.

Urgency and threat to human life, paired with suspicion of both method and motivation, permeates both works. The two poems are emblematic of the complex relationship Kane and Kinsella have adopted with the renga form; this is a collaborative poetics in politics, embracing the traditional symbolic theory of no distinct hierarchy of voice, communal assumption of responsibility by the two speakers, rather than perfect mirroring of traditional syllabic structure. But this is also a form that intrinsically excludes voices and control; the lead poet sets the tone and theme, and the later poets must follow. Absent voices – the colonised people of the countries flagged in the collection, lands, animals – are excluded from this hierarchy by nature of the form, but not with intent to oppress. However, moves are taken ensure that these experiences are not excluded, as in Kinsella’s “Renga 64”:

… Today, the sky is wheatbelt blue.

The still leafless trees shimmer a silver-green

Of what’s to come. Premonitions.

Though it’s all black and white.

I grew up with black and white television.

We don’t watch television now

Which is said to be in colour. As is Nature.

I’ve contributed to this knowledge. This rumour.

A sense of personal culpability is incorporated into this reflection of marginalised binaries, though no direct voice is given to those oppressed groups. Throughout the collection there is pressure to revise oppressive angles, recognising destruction and destructive tendencies wherever they may appear.

In “Echolocations: An Afterword”, Kinsella addresses the thematic concerns of place, mutual concern, co-writing, and the ethics of belonging. This is a collection of “commonality amidst the difference” as “Words crosstalk, lines subscript, and yet each line is ‘intact’, a moment in a place sent across a vast distance” but not without anxieties (115). Selection of the renga style for this long-running dialogue across continents brings to the forefront the importance of shared experience rather than subsumed voice, and the need to make meaningful connection.

References

Timothy Clark, “”Renga”: Multi-Lingual Poetry and Questions of Place”, SubStance

Vol. 21, No. 2, Issue 68 (1992), pp. 32-45.

Roy Starrs, “Renga: A European Poem and its Japanese Model”, Comparative Literature Studies, Vol. 54, No. 2 (2017), pp. 275-304.

SIOBHAN HODGE has a Ph.D. in English literature, her thesis focused on feminist traditions in translating Sappho’s poetry. She had critical and creative works published in a range of places, including The Fremantle Press Anthology of Western Australian Poetry, Westerly, Southerly, Cordite, Plumwood Mountain, and Peril. She has won several poetry awards, including the Kalang Eco-Poetry Award in 2017, 2015 Patricia Hackett Award for poetry. Her new chapbook, Justice for Romeo, is available through Cordite Books.

September 4, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

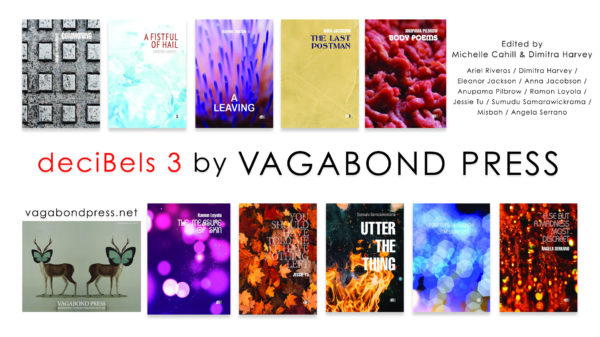

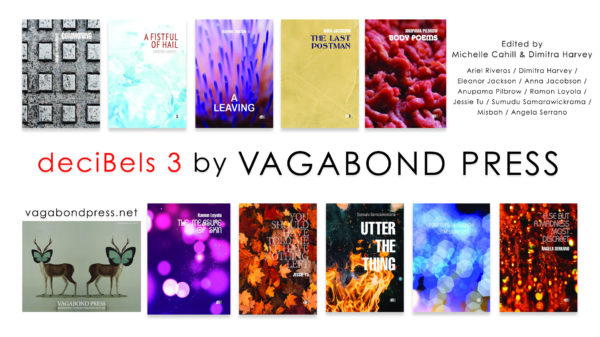

deciBels3

Vagabond 2018

Edited by Michelle Cahill & Dimitra Harvey

Launched by EMILY STEWART

How to mobilise the launch speech? An essay in the form of a thread

I have been metabolising Michelle Cahill’s work on interceptionality, a term she has been dissecting and championing over three essays with the Sydney Review of Books, the latest published this week. I am deeply interested in her rich theorisation, which is seen in practice with the activism of Mascara Literary Review, interception being a pragmatic, principled approach that can, in Michelle’s words, ‘unmask entitlement and inaugurate dialogue’ but which also, and this is really important – offer creative protection. Creative protection, because the intercepts that Michelle enacts are highly generative actions. Her activism – each tweet, email, newsletter – that calls for better representation and equitable opportunities for CALD writers opens up new sites of potential. I’ve been thinking through what the use of a launch speech might be within an interceptional framework – and indeed where it even fits within the publishing ecology, as it’s not a review, or criticism, but is significant nonetheless, creating a shape and a language for how books will be talked about by others. The launch speech is a powerful object as it oftentimes sets the tone for the critical discourse that will follow. So how to mobilise it?

Introducing deciBels 3 chapbook series, edited by Michelle Cahill and Dimitra Harvey

The format I have chosen acknowledges the extraordinary event that is the deciBels 3 chapbook series: the release of ten books all at once is a powerful statement that actively works against received publishing logics; where books are published individually and given their own run before the next appears. This collectivist, connective model has impact – it is an opportunity for CALD writers to hold more space together than they would individually. But I have also been sensitive to making sure that each book gets its due.

Furious summations: Eleanor Jackson’s A Leaving

‘The amniotic place / of rejection from which we are born’. Jackson is drawn to moral complexity found here in infidelity, at a conference, on death row. These are poems as furious summations. In ‘Remembrance Day’, she writes, ‘Don’t let me wallow in generalities’ – the imperative drives these poems. Can’t let emotion distract from incisiveness, poetry needs both. There is great range in this small book, which is deeply invested in the world – the poet listens closely and the poems enact that listening, moving between a restrained political persona and a tender, more buoyant self.

Peace inside the unresolvable: Dimitra Harvey’s A Fistful of Hail

Cross-pollinations: A line of Eleanor Jackson’s, ‘the caesura between the outage and the back-up’ precisely describes the work of Dimitra Harvey’s poems, their electric holding of space within/around/after moments of brutality – can a poem act as a coda to violence? Or is violence inherently without coda? How to find peace inside the unresolvable – see the poems ‘Father’, ‘Acrocorinth’, ‘Sport’. Contradictory as it may seem, through the sonic the poems resist the structural confines that also give the poems their admirable pressure – they resonate. From ‘Station’: ‘A woman’s laugh, the clink of glasses – the city’s noises are padded here. Then a whip of wire, a spring-loaded lash. The train pulls up, groaning in its metal’.

She is so free: Angela Serrano’s Else But a Madness Most Discreet

The libidinous haze of Angela Serrano’s sex-positive poems strikes immediately; their temperature – hot – because they fully embrace the abject. Case in point: the book’s first poem begins with its speaker taking a shit. Later in the book: ‘At first I thought the fog was from a fire’. But the reader knows by then that Serrano’s fog is a pleasure-full fugue. And something else – ‘intersections are Freudian hotspots’. The poems at the centre of the book are presented in Tagalog first, then English. The poetic persona’s largesse, appetite, ambition. Her fluidity, open pursuit of desire – she is so free.

Details of light: Anna Jacobson’s The Last Postman

Speculative, epistolary, characterful. Sensorial – keyed into atmospheres. Details of light. ‘The sun as it performs its yoga’. More volatile: ‘I was walking in the same direction as you – watched you crush a lit cigarette into your pocket’. A spectral parsing in ‘Letter 7’, the opening line ‘water damaged eyes are made whole again’. The poem makes uncanny the relation of body and material. (But then, perhaps this is always? Uncanny.) ‘Your job is to erase these paper bruises’. At first a poem about the reconstructive efforts of memory, but at a certain point it’s occulted. ‘You pick up the stylus, graft pixels to creases’.

I turned the word over and over: Ramon Loyola’s The Measure of Skin

Measure – restraint? Measure – wager? I turned the word over and over as I read these love poems. These poems about touch, and skin. Also, consistently, about the transgressive power of looking. (That overblown phrasing is mine alone. Loyola is considered – measured. This measure, its considered restraint, holds erotic charge (so there is something at stake – a wager). One of these poems is among the best sex poems I’ve ever read. Every one of these poems is a blueprint for cultivating deep courage in the pursuit of self-knowledge: ‘I’m afraid to look but I must, I must, without hesitation’.

The book with flames on its cover: Sumudu Samarawickrama’s Utter the Thing

These poems often take place at dusk, the casting of ambiguous time, where there is still – just – enough light for colour. In the poem ‘Smoothas’ this state is described as ‘lavender gloaming’, and it imbues the poems with a heightened sense of drama where all senses are labile, on alert.

Kinetics in the poem ‘power/move’, that slash is some/one and they are changing their position.

Kinetics in the poem ‘The Lug’, where a door opens and time jump cuts and words run-in-to-each-other-so ‘Ipretend’, ‘myvoice’, ‘feigningconsistency’. The speaker is not safe.

Kinetics in the poem ‘Anger Poem’: ‘I’m writing this story over this story I wrote The same story.’ The great repetitions of being in experience.

Trajectories: Jessie Tu’s You Should Have Told Me We Have Nothing Left

Intimate examinations of women’s lives and their various trajectories. How do we become who we are, or perhaps more importantly, what happens to us? The poem ‘And it is what it is’: ‘You are given fingers before a mouth’. The poem ‘The Hotel’, its speaker taking and loading, taking and loading her luggage, she is ‘always arriving’. The everyday questions that comprise life’s form: when to fight for a relationship, whether to have a kid.

But then with the poem Going there where there is no place to go, Tu dissolves the very notion of trajectory, she tips the poem on its side.

Read in the usual way, English-language lines travel forward. At this new angle they pull backwards. Our past grows with us – fact. How to keep moving?

She writes, ‘The only possible answer to this problem with no solution is to keep turning up’.

Twice-ness: Ariel Riveros’s Commoning

From the opening poem ‘Bel Canto’: ‘Your image comes up and I’m speaking to your photo as well as to you’. Riveros’s poems always speak twice, but FYI I’m using ‘twice’ as a placeholder for ‘multiply’. The twice-ness of these poems causes little rips in time, so that ‘a medieval of plastics reach the waterways’ and ‘order of truth is no flicked lumiere’. In the poem ‘Paen to a 1996 nervous breakdown’, ‘some maps are lost in themselves / and territories that we’ve not onedered but twodered and now we’ve threedered and can fourded’. Multiplicity can quickly become terrifying – it does so for me in the portentous ‘A Poet Knows When’, which opens with the lines ‘Right up against me/ before sleep/ after waking/ I carry carcass’. That carcass is multiple, carried by and speaking to the poet, but appearing in a second form as well, as ‘carcass earth’. Anything can, and has, and does and will happen – but the shadow to this, the question of accountability, is ever-present. The Melbourne poem ‘Settlement’ in particular troubles notions of political ‘progress’ (even and especially as it doubles, triples): ‘The bum is the seat of Parliament as we get to the following station’.

Notes from a homing pigeon: Misbah’s Rooftops In Karachi

Misbah’s clipped, urgent missives report on Karachi, Pakistan, the city of her birth; and on her subsequent travels there, real and imagined. In their small, tight prose forms, they can be read like notes from a homing pigeon – and indeed one such pigeon appears in the very first line of the book. Each missive or note is highly architectural in its construction; a memory palace. From the poem ‘Territory’: ‘Under my skin is a mosque buried, over its surface borders are patrolled, in the lines of my hands are partitions of space occupied by warring microbes building temples of salt’. This precision also recalls tactics of surveillance; a thorough updating of the homing pigeon metaphor – so while the poems sometimes speak to place, at other times they register site. Often, and as in the poem ‘Last Transcript from Osama’, presented here in full, there is an interleaving: ‘X marks the coordinates of clouds disconnected, the colour of bandages, the colour of sleep, uniforms, and especially ambulances and weddings, kites on wires, the soft calligraphy of fighter pilots, and rooftops that are in every way the surface of the moon’.

A loop, hoop, circle: Anupama Pilbrow’s Body Poems

Pilbrow’s interest in exchange, reciprocity, relationality is signalled in the book’s dedication before readers even get to the poems. I hope she won’t mind me sharing it: ‘To my family. I love them and they love me’. A Pilbrow poem rolls forward as a loop, hoop, circle. Almost every poem is its own category of poem (as in they are called ‘Body Poem’,’Membrane Poem’, ‘Despicable Body Poem’, ‘Trying to Remember My Birth Poem’, &c. While wellness culture promotes the present as a desired state of calm, in Pilbrow’s Poem-poems, the present is absurd, fantastic, gross. From ‘Ocean Poem’: ‘I have a bath and I shave my legs underwater so all the hair pieces are swimming in the bath water with me’. Her forensic descriptions are also-always ebullient – how? ‘Hold the bone and scrape it hard against concrete or volcanic rock to shear away soft and round bits until the bone is a weapon’. A cool new mantra.

I wish each of these brilliant writers every possible success

Congratulations to editors Michelle Cahill and Dimitra Harvey, with the support of Michael Brennan and Vagabond Press, for their fearless and clear-sighted editorial vision, for bringing ten impassioned, uncompromising and beautifully moving books into the world all at once.

EMILY STEWART is poetry editor at Giramondo Publishing and a doctoral candidate at Western Sydney University where she is conducting research at the intersection of poetry and architecture. Her first collection Knocks was published by Vagabond Press in 2016 and received the Noel Rowe Prize.

August 6, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

From cultures of violence to ways of peace: reading the Benedictus in the context of Australia’s treatment of asylum seekers in offshore detention

Revised version of a paper given at ‘Things That Make for Peace: Peace and Sacred Texts Conference’, hosted by School of Theology & Centre for Islamic Studies and Civilisation, Charles Sturt University, at United Theological College, North Parramatta, 7–9 March 2018.

The author acknowledges the traditional owners of the Parramatta area: the Burramattagal people of the Darug nation, and pays her respects to the elders past, present and emerging, recognising their continuing connection with and custodianship of this place, especially the river.

***

On 31 October 2017, the Regional Processing Centre housing asylum seekers in detention on Manus Island—many of whom had been confirmed as refugees—was closed. For months beforehand, the men detained, as well as refugee advocates and agencies, had warned that the Australian and Papua New Guinean Governments had not properly prepared for this closure. Around 600 men were to be moved to facilities in Lorengau, Hillside Haus and West Lorengau; supporters and human rights observers reported that these facilities were unready. Moreover, before the date for transfer, essential services of food, water, medical care, power and security were phased out and finally withdrawn. The men who had already been protesting their detention and impending forced transfer to sites they believed, with reason, to be unready and unsafe, refused to be moved. They staged a nonviolent resistance for 22 days from 31 October to 22 November 2017 when they were forcibly removed and transported to the new facilities.

Of the months leading up to the closure of the Regional Processing Centre, Behrouz Boochani, a Kurdish journalist and writer from Ilam in Iran, who had already been held on Manus Island for over four years, wrote: ‘For many months, the refugees living inside Manus prison have had to endure extraordinarily oppressive conditions orchestrated by the Australian government’ (‘Letter’). Though not the only public voice among the detainees, Boochani—especially through his articles in The Guardian and The Saturday Paper, and his daily Twitter and Facebook posts—became a key communicator of the men’s situation to Australians, calling both people and government to account for the treatment of asylum seekers and refugees on Manus and Nauru. The nonviolent action of the men, and the response to it by Papua New Guinea officials in collaboration with the Australian Federal Government, became a test case for the ongoing Australian policy of offshore detention. For many Australians, it is clear that offshore detention is neither sustainable nor desirable, and needs urgent change that is tragically not forthcoming. Many, however, remain indifferent.

Serially, since the time of the Howard Government’s response to the sinking of the Siev X in 2001, Australian Governments—both Coalition and Labor—have enacted policies of border protection where deterrence of people arriving by boat, using so called ‘people smugglers’, are based on cruelty to detainees, though arguably such cruelty has escalated under the current Coalition Government.

In this essay I focus on Australia’s treatment of asylum seekers in detention, particularly in those three weeks from 31 October 2017. The issue is not resolved, as recent reports of inadequate medical care—particularly in mental health—for detainees on Nauru and in the new facilities on Manus indicate (e.g. Davidson 2018a; Syed 2018). Since the forced transfer of the men, however, the Australian media has largely lost interest and even public Australian activism has died down, though there were rallies on Palm Sunday (25 March 2018) for refugees; on 1 March 2018 Asylum Seeker Resource Centre in Melbourne launched a campaign to #changethepolicy; and between 16 and 22 July 2018 #FiveYearsTooMany rallies were held around Australia.

Writing of ‘Undocumented Immigrants, Asylum Seekers, and Human Rights’, Mark Brett (2016, 163–64) comments, ‘The raw numbers of people seeking asylum in Australia, especially when considered in relation to national wealth, barely rate a mention in international analyses, yet national elections in Australia have been known to turn on “border protection” policies. / What, then, can biblical theology and ethics hope to contribute to the debates?’ In conversation with Habermas, Brett (2016, 35) sees a role for biblical theology in public discourse not in service of a ‘unified public culture, but rather, by a thickening of dialogue between religious and non-religious traditions’, so that ‘theological ethics towards the marginalised … inform’ political praxis. In this essay, I bring into conversation Boochani’s ‘A Letter from Manus Island’ and the Benedictus, a biblical hymn, understood as songs of protest. My aim is to suggest what might be elements of a cultural shift from violence to nonviolence, and what this shift should mean in relation to public response to offshore detention of asylum seekers.

Protest writing

Warren Carter (2011) identifies four key and ‘interweaving dynamics’ of African American and South African performative songs of protest from the US slave, civil rights, and South African apartheid eras. They are:

‘naming contexts of oppressive suffering’

‘bestowing dignity’

‘fostering hope for change’

‘securing communal solidarity’.

Carter applies these dynamics to an analysis of the songs of the Lukan infancy narratives (especially, The Magnificat and The Benedictus) and reads these as songs of protest in the context of oppressive Roman occupation and empire.

Briefly, Carter argues that in a theo-political frame the songs encode the perspective of the marginalised and name aspects of Roman empire as a context of oppressive suffering: in the Lukan songs the imperial social system of domination, resulting in economic oppression, operates contrary to divine purposes and results in the people’s need for divine assistance. The songs bestow dignity by construing the people and the divine as interrelated, as kin, with the divine present to the people. Carter (2011) writes:

The songs function to bestow dignity in the midst of dehumanizing oppression by naming the relationship with God, celebrating the favorable divine disposition experienced in their midst, recalling benign and faithful covenant commitments, awaiting vengeance, and echoing songs of previous interventions.

Interrelated is the way the songs offer an alternative vision of reality and so provide hope through appropriating and transforming key facets of Roman society; in the context of the Gospel of Luke, they offer a vision of release from debt and a peace different from the Pax Romana which functions as a tool of domination reinforcing the status quo. Finally, for Carter (2011), the songs suggest a communal understanding spanning past, present and future, and defining ‘community as one that benefits from’ divine intervention. Communal solidarity is secured by divine promise, and resists or unsettles the existing societal order with an alternative social vision.

Nonetheless, as Carter (2011) notes ‘the songs do not only resist, they also imitate and perpetuate the imperial structures that they oppose’. To some extent, this mimicry is inevitable, but the re-inscription of empire is a significant factor in the ways violence and nonviolence appear in the song of Zechariah (the Benedictus). Before I turn more closely to this song, I examine a description of nonviolent action in the face of violence, in Boochani’s ‘A Letter from Manus Island’.

Behrouz Boochani’s ‘A Letter from Manus Island’ and other writing

Boochani’s ‘Letter’ exhibits the four features of protest writing that Carter nominates. It begins with a description of a situation of oppressive suffering experienced by the detainees on Manus Island, naming the Regional Processing Centre and the new facilities as prison camps and the treatment of the 600 refugees who refused to move on 31 October 2017 as a regime of ‘extreme force and dictatorship’ (‘Letter’). Reports from Boochani, other detainees, visitors such as Tim Costello, Jarrod McKenna, and UN and other human rights observers during the 22 days of nonviolent protest tell of no provision of food, water or medical care, failed security, destruction of property by local officials, and piercing of makeshift water tanks, among other things.

Boochani writes of the way the men responded by claiming their dignity as human beings. This was vital to their action. He says: ‘The refugees were able to reimagine themselves in the face of the detention regime’ (‘Letter’). They resisted their characterisation as the ‘passive refugee’ that the Australian government had constructed as exploitable for their own political ends, and asserted ‘that we are human beings’ (‘Letter’). Central to this assertion was the men’s claiming of their freedom. This was not simply freedom as a future hope—that is, freedom from detention, though of course this was fundamental. They also asserted a deeper, hard-won—and in the circumstances difficult to sustain—freedom while in detention: to act as human beings with authority and choice. Boochani (2017c) describes this assertion of freedom as the key motivating factor for their action, in contrast to the practical reasons adduced by supporters—for example, the inadequacy of the new detention facilities. At one level this was a freedom that cried ‘enough is enough’, ‘we will not be moved from one prison camp to another prison camp’ (Boochani 2017c). At another level, this drawing the line was a claiming of their shared humanity.

Freedom gave hope in their shared situation. Boochani writes: ‘We learnt that humans have no sanctuary except within other human beings’ (‘Letter’). Given the intransigence of the current Australian government concerning offshore detention, evidenced in the tone of what one friend in Melbourne describes as the ‘robot letters’ from Peter Dutton MP’s office, it is hard to see how hope is possible. But both in his ‘Letter’ and elsewhere, Boochani (2017e), describers the way the land of Manus and its surrounding sea were sites of hope, as:

the violence designed in government spaces and targeted against us has driven our lives towards nature … since we hope that maybe we could make its meaning, beauty and affection part of our reality. And coming to this realisation is the most pristine, compassionate and non-violent relationship and encounter possible for the imprisoned refugees in terms of rebuilding our lives and identities. (‘Letter’)

The choice the men took, while sustained by the surrounding beauty of the natural world when there was little else to sustain them, also secured a sense of communal solidarity. Boochani’s ‘Letter’ describes this solidarity in terms of democracy, respect for the freedom of each, care for the sick, sharing of food, co-operation concerning provision of vital needs, and cross-species kindness. What his description, his protest writing, adds to Carter’s analysis of African American and South African performances of protest, moreover, is this: an articulation of a political poetics. ‘Our resistance’, Boochani writes, ‘enacted a profound poetic performance’; ‘it was an epic of love’, he says (‘Letter’). Moreover, for Boochani, this resistance is a challenge to Australians’ self-perception, a haunting which I suggest echoes the haunting of Australia’s colonial past and present in relation to Indigenous peoples: ‘[Australians] would come to realise something about how they imagined themselves to be until now. … regarding their illusions of moral superiority’ (‘Letter’). He writes, ‘Our resistance is a new manifesto for humanity and love.’