May 25, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

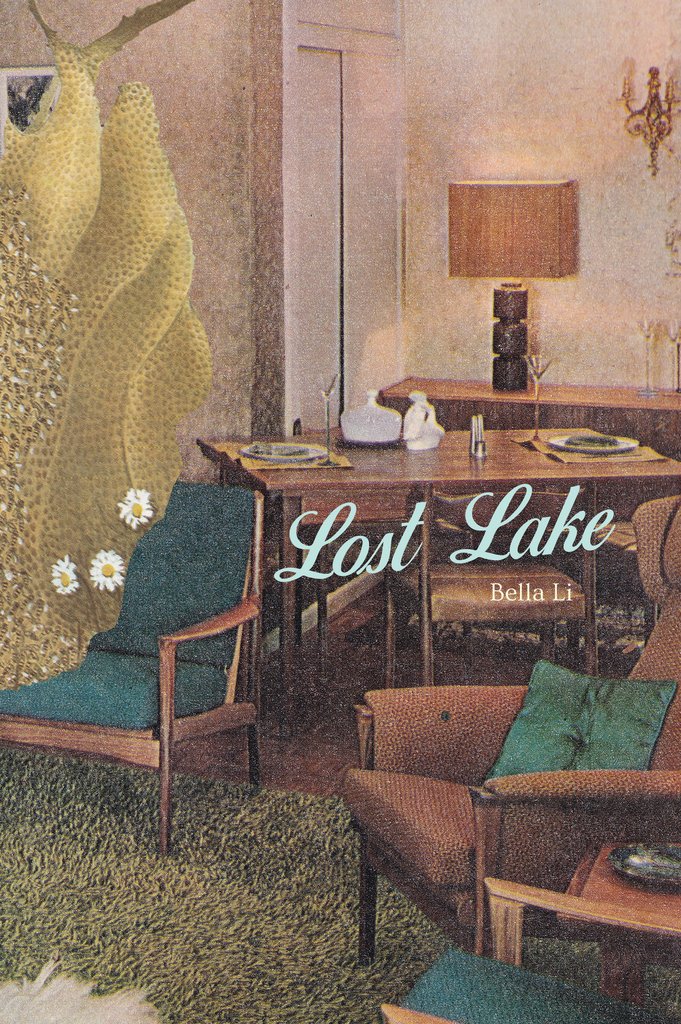

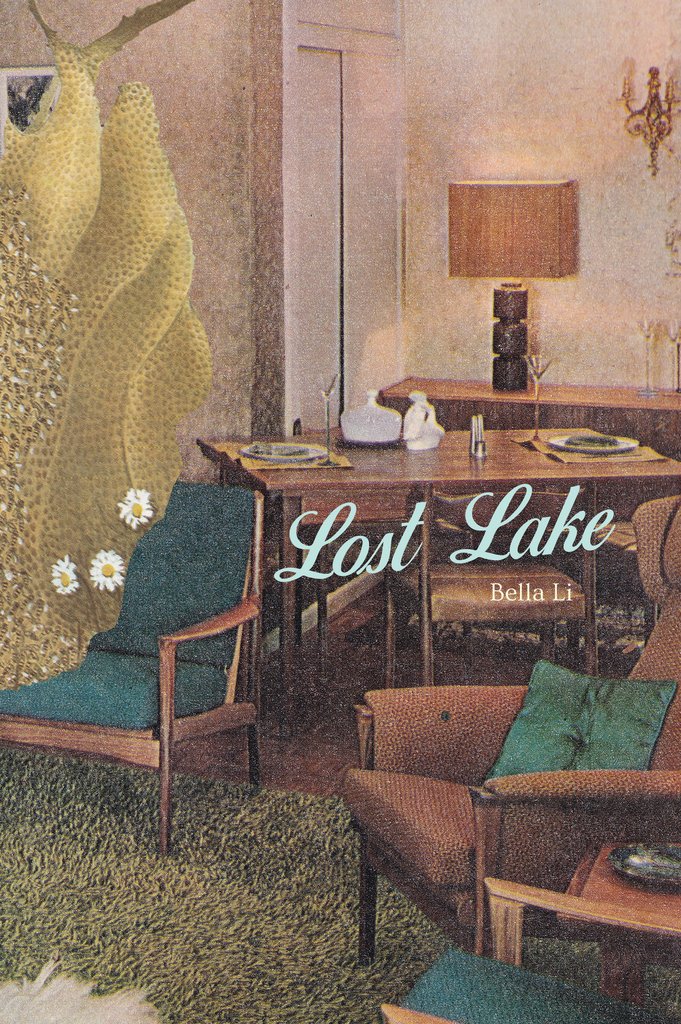

Argosy and Lost Lake

Argosy and Lost Lake

by Bella Li

ISBN 978-1-922181-96-1

ISBN 978-1-925735-18-5

Vagabond Press

Reviewed by JENNIFER MACKENZIE

A publishing highlight of 2017 was the appearance of Bella Li’s Argosy, and this has been followed by the recent release of Lost Lake. By introducing an intriguing blend of collage, photography and sparely-written text, the poet has provoked, as well as enthralling us with her original poetics, a fresh way of looking back on some poetic traditions, particularly that of Surrealism. Although a number of responses present themselves for discussion, I shall focus on what is a dominant focus in both collections, that of the journey. With the theme of voyages or journeys reverberating through Argosy and Lost Lake, they reveal themselves as an imminence, in which all images and words surrender into an inevitable beauty.

It is apt indeed that the principle poem in Argosy, Perouse, ou, Une semaine de disparitions, connect the maritime expeditions of La Perouse to the collage novels of Max Ernst, these being Une semaine de bonte: A Surrealist Novel in Collage, and The Hundred Headless Women. The voyages of such explorers as La Perouse and Bougainville were a major inspiration for several French writers in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In prose, Balzac, Flaubert and Proust come to mind, and in poetry the influence appears considerable when we think particularly of Gautier, Segalen, Baudelaire and Rimbaud. Rimbaud, with his notorious and basically unrecorded escapade to the then Netherlands East Indies provided in A Season in Hell, a picture of the endgame in colonial domination : ‘ the white men are coming. Now we must submit to baptism, wearing clothes, and work’(1)

Apollinaire, one of Li’s sources in Argosy, coined the term ‘Surrealism’ in regard to the ballet Parade, created for the Ballets Russes in 1917 by Massine, Cocteau, Picasso and Satie, a ballet in which disruption of surfaces and sound, with noise-making instruments and cardboard costumes, confounded aesthetic expectations. As Surrealism developed in both literature and art, Max Ernst led the way with his collages, so integral to the method in Argosy. The artist described the technique as ‘the systematic exploitation of the accidentally or artificially provoked encounter of two or more foreign realities…[to bring about]…a hallucinatory succession of contradicting images’.(2)

What Li has achieved in Argosy is quite remarkable. In La Perouse, the voyage is depicted as hallucinatory, a collage of surrealist dreamscapes, of oceanic encounters which liberate the ekphrastic from its often reproductive impetus. With language taken out of its temporality, an archaic texture creates its own spatial idea and its own measure. At this point, I would like to refer to Ernst’s technique of frottage, where as the artist stated ‘the boundaries between the so-called inner world and the outer world became increasingly blurred’. There is a sense in the restraint in the use of language in Argosy, in the deft rise and fall of the poetic line, in the masterly control of phrase and silence, that the measure itself delineates erasure, delineates trace.

It is fascinating to see in Argosy how collage and text situate each other, not as complimentary or elucidatory, but as transforming the actual experience of reading and of viewing into the poetic intention. The collages, with their gargantuanism, their contrast between the splendour of the discovered and the sometimes small scale of the discovering, the extensive use the avian directly inspired by Ernst, play on the monstrosity of the quotidian. To quote from the text seems something of a travesty, considering how well the sections knit together, but in jeudi: Les reves we are immersed in the experience of the speaker, the measured voice containing a flourish of an image, Our man at the helm, broad-shouldered and in love, suggestive of other worlds that remain unspoken, or only hinted at:

This day we sail, dividing the waters from the heavens. I am

my own guide, the steerage, the hull. This day by sea, by the

sea we lie. Sharp peaks divided, three by two by three. Our

man at the helm, broad-shouldered and in love, saying: This

but not this. This, but not this.

You ford the stream. You move. (52)

And in the final text section, samedi: Les incendies, there is a sense of fatality and an acceptance at the end of a journey which always portended the abyss:

In the perilous passage, prepare for death.

Though tempests rage, take shelter in fate.

At every harbour, seek solitude and rest.

Through sickness and sorrow, find solace in faith.

On days of fine weather, breathe and drift.

When evening comes, set fire to the ships.

Everything lies. Everything lies to live.(84)

Before that, in what is one of the most telling passages in this section, we find La Perouse, with his companion M. Lavaux, looking down into what seems the very essence, or being, of the world:

Morning on the dim shore, hours coming and going. We step

down, M. Lavaux and I, to the water’s edge. Mirror of the

world as it dips and slides from view, wave beginning its slow

path to infinity. There we discover the first of the objects, of

which I will relate only. The barest details, ashen. Though the

day will begin and begin again. Though we meet, he and I, with

no sign of land. Circling, in the upward draughts, a curious

sight: Buteo buteo. Buzzards, so far south.(79)

This seems to be a good point at which to turn to Lost Lake, which displays a further development in the integration of image, text and theme. Sourced texts resonate through the poetry, which raises some interesting questions about how we read, about how images resonate or reside within the imagination. Recently I attended a talk given by the artist John Wolseley, during an exhibition of his work at the Australian Galleries in Melbourne. At one point, he was discussing the importance to his own work of Max Ernst and his technique of frottage, of how the technique enables both erasure and emergence, that an image may ultimately reveal itself as if from the beginning of time. In Lost Lake the language does something comparable, as it is deliberately set out of context or any quotidian reference, having a tone placed somewhere between the Bible and Calvino. In relation to the way photography and text play into this field, especially in terms of natural imagery and this veering to the origin, a comparison could be made with the cinema of Terrence Malick, where the voice, spoken into the creative space rather than being merely perceived as dialogue, forms an imminent connection with it.

At the same time, however, this seemingly shared method stresses the isolation, the ‘out-thereness’ of everything. Such a sense can be found in the sequence Confessions. Eighth is a stellar example of this intent:

That the entire forest was plunged as though under a sea. As

at the beginning of the world, as if there were only the two. So

was I speaking when – with a more premeditated return, with

more precision, as though upon a crystal glass- I asked my

soul why she was so. Over the forest did my heart then range.

I shut the book. And I cannot say from which country, which

time, I cannot say from which it came. (44)

Also in Confessions, in Sixth, there is a hint of Zen:

There are sounds I do not hear. Sometimes, at the edge of

water and surrounded by trees.(43)

and in Second, there is an apprehension of home, but also not-home, that dwelling is but an absence, a shadow:

That what I have seen I have seen from houses. That in my

father’s house was a strange unhappiness. That I had searched

for it, in my life, in the hollows of doors, that I had found it,

that it had found in my home. And in my home I had neither

rest nor counsel. The days, the soul of man riveted upon

sorrows; now and then the shadow of a woman, in the far

corners of the house.(41)

Grand Central, in a stunning series of images, presents another form of the journey, this time by rail. The poem brilliantly situates composer Steve Reich’s composition, Different Trains, where his wartime experience as a child of regularly shunting across the United States, splices with the European temporality of Hitler’s death trains. Lost Lake concludes with the luminous sequence The Star Diaries. The journey/s and its/their destinations are varied and unsettled. Home is unattainable, but the journey continues in dystopian fashion. One thinks of the sourced Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, but also the work of that one-time Surrealist, Rene Char. Presences appear and vanish like a shadow as in The Eighth Voyage:

… I must have been ill because I can’t recall. But I remember him

standing there in the shadows of the firelit room, barefoot.

Calling me by my name. In the following weeks the radiation

decreased, a slow bleeding away. Then the quiet zero weather

broke. And we continued – me one way and him another.(134)

Further on this sequence in the vision becomes apocalyptic:

…Drifting over former

libraries and museums, all sunk beneath the jelly-green water.

The old scow navigated, under a white moonlight, past ghostly

deltas, luminous beaches; each in their turn submerged and

sinking. Overhead, dusk was vivid and marbled. Clouds of

steam filling the intervals between buildings, motionless and

immense; silt tides accumulating in dense banks beyond th

concrete reef. Darkness fell. In the surrounding suburbs the

streets were filled with fire until four o’clock.(135)

The textual sequence ends with a statement of record in The Twenty-fifth Voyage:

I am obliged to give an account of what I saw: a moving

walkway, slowly unreeling. On the ocean surface, something

moving. Something looked like a garden; I recognised an

apiary. Sometimes seemed to be standing upright, sometimes

lying on its side. There occurred a magnetic storm and the

radio links were cut.(151)

The Twenty-eighth Voyage presents a vision of a conservatory.

Both Argosy and Lost Lake are beautifully presented and designed. They are a pleasure to look at and to hold, and both collections raise as many questions as you may care to ask.

NOTES

1. Translation by Jamie James in his Rimbaud in Java, Editions Didier Miller, Singapore 2011, 69

2. Quotations from Max Ernst in www.modernamuseet-se>max-ernst

JENNIFER MACKENZIE is a poet and reviewer, focusing on writing from and about the Asian region. Her most recent work is Borobudur and Other Poems (Lontar, Jakarta 2012).

May 6, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

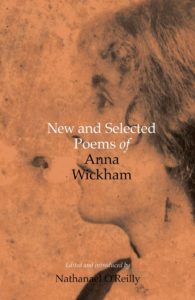

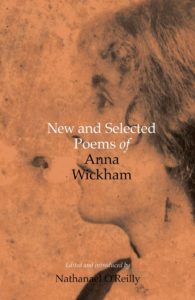

New and Selected Poems of Anna Wickham

New and Selected Poems of Anna Wickham

Edited and Introduced by Nathanael O’Reilly

UWA Publishing, 2017

ISBN 978-1-7425892-0-6

Reviewed by KATIE HANSORD

The significance, value, and breadth of Anna Wickham’s poetry extends beyond categories of nation and resists the limitations of such categories. The category of woman, however, is central to her poetics, as both a culturally ‘inferior’ and structurally imposed designation, and as a proud personally and politically conceptualised identity, and marks Wickham’s important and consistent feminist contribution to poetry. ‘As a woman I have no country. As a woman I want no country. As a woman my country is the whole world’ (Three Guineas 197) are the words Virginia Woolf once chose to express this sense of solidarity with other women beyond national borders. Born Edith Alice Mary Harper in 1883, in London, Wickham lived in Australia from the ages of six to twenty, later living again in England, in Bloomsbury and Hampstead, as well as living in France, on Paris’ Left Bank. Wickham is noted to have taken her pen name from the Street in Brisbane on which she first promised her father to become a poet, and the early encouragement of her creativity was to be a seed which would grow and continue to bloom despite cultural bias and personal circumstance, including the opposition of her husband to her writing, and institutionalisation. She was connected with key modernist and lesbian modernist figures including Katherine Mansfield, and Natalie Clifford Barney, whose Salon she attended, becoming a member of Barney’s Académie des Femmes, and with whom she is noted to have ‘corresponded…for years, expressing passionate love and debating the role and problems of the woman artist’ (Feminist Companion 1162).

Wickham’s poetry represents a significant achievement within early twentieth century poetry and can be described as deeply concerned with an activist approach to issues of gender, class, sexuality, motherhood, and marriage. These are all issues that address inequalities still largely unresolved, although in many ways different and understood quite differently, today. These poems may be playful, experimental, self-conscious, and passionate poems that are varied but always conscious of their position and their place in terms of both political and poetic traditions and departures from them towards an imagined better world. In the previously unpublished poem ‘Hope and Sappho in the New Year,’ Wickham boldly suggests both lesbian and poetic desire and a class-conscious refusal of bourgeois devaluation as she asserts:

Let Justice be our mutual gift

Whose every prospect pleases

And do not mock my only shift

When you have three chemises

Then I will let your chains atone

For faults of comprehension-

Knowing you lived too long alone

In worlds of small dimension.

A refusal to accept such ‘worlds of small dimension’ reiterates the inclusion of emotional, psychological and structural disparities, as have frequently been noted in her previously published poem ‘Nervous Prostration’, in which she describes her husband as ‘a man of the Croydon class’ (New and Selected 19) and in which she plainly and honestly addresses the structural and emotional complexities of her heterosexual bourgeois marriage.

In poem ‘XX The Free Woman’ Wickham outlines a moral and intellectual approach to marriage for the woman who is free, writing:

What was not done on earth by incapacity

Of old, was promised for the life to be.

But I will build a heaven which shall prove

A lovelier paradise

To your brave mortal eyes

Than the eternal tranquil promise of the Good.

For freedom I will give perfected love,

For which you shall not pay in shelter or in food

For the work of my head and hands I will be

paid,

But I take no fee to be wedded, or to remain a

Maid.

Wickham’s poetry is notable for its balanced concision and depth as much as for the expansive, inclusive, intersectional approach it takes. I am using the term intersectional to refer here to an approach which is understanding of the interconnected nature of oppression in terms of gender, class, and sexuality, although it should be acknowledged that the poems do not tend to address issues of racism specifically.

New and Selected Poems of Anna Wickham, edited and introduced by Nathanael O’Reilly, brings together for the first time in print a wide inclusion of previously unpublished poems, gathered from extensive research into Wickham’s archive at the British Library. Significantly, O’Reilly’s thoughtful and careful editorship of this collection restores Wickham’s original versions of the published poems included, as well as presenting the unpublished poems in their original style and punctuation, giving the reader a clearer sense of the poet’s intention and expression. One such example is the sparing use of full stops in the poems, suggesting again Wickham’s expansive, inclusive, and flowing mode that defies the limitations of ‘worlds of small dimension’. Until this publication, readers have not been able to access these poems in print, and the majority of Wickham’s poems, over one thousand, have not been in print. Sadly, some of her writing, including manuscripts and correspondence, was destroyed in a fire in 1943. This new collection includes one hundred previously published poems as well as one hundred and fifty previously unpublished poems, making it a substantial and impressive feat. Wickham’s published collections, now out of print, included Songs of John Oland (1911), The Contemplative Quarry (1915), The Man with the Hammer (1916) and The Little Old House (1921) and she had a wide reputation in the 1930s. This expanded collection of her poetry then, is to be warmly welcomed and applauded as a timely extension of the available poems of Anna Wickham, following on from the earlier publication in 1984 of The Writings of Anna Wickham Free Woman and Poet, edited and introduced by R.D. Smith, from Virago Press, and before that her Selected Poems, published in 1971 by Chatto & Windus, reflecting the renewed interest in Wickham during the women’s movement of the 1970s.

These previously unpublished poems give further insight into Wickham’s experimentation, variation of form and style, and poetic achievement. Jennifer Vaughn Jones’ A Poets Daring Life (2003) and Ann Vickery’s valuable work on Anna Wickham in Stressing the Modern (2007) as well as that of other Wickham scholars, may more easily be expanded upon by others with the publication of this new extensive collection of Wickham’s poetry. Although Wickham’s works are now much more critically recognised than has been the case in the past, it is to be hoped that the publication this new collection will go some way to further redressing what has tended to be seen as a baffling lack of critical attention for such an important poet. Equally importantly though, the publication of this collection opens out an expanded world of Wickham’s writings to all readers and lovers of poetry wanting to engage with a poetic voice that so eloquently and purposefully brings to the fore the issues of justice, equality, gender, and both the societal and personal freedoms that remain so crucial and relevant to readers today.

NOTES

Blain, Virginia, Patricia Clements and Isobel Grundy (Eds). The Feminist Companion to Literature in English, Batsford: London, 1990.

Vickery, Ann. Stressing the Modern, Salt, 2007

Wickham, Anna. The Writings of Anna Wickham Free Woman and Poet, Edited and introduced by R.D. Smith, Virago Press, 1984.

Wickham, Anna. New and Selected Poems of Anna Wickham, Edited and Introduced by Nathanael O’Reilly, UWAP, Crawley 2017.

Woolf, Virginia. Three Guineas. London: Hogarth Press, 1938.

KATIE HANSORD is a writer and researcher living in Melbourne. Her PhD thesis examines nineteenth century Australian women’s poetry and politics. Her work has been published in ALS, Hecate, and JASAL, as well as LOR Journal and Long Paddock (Southerly Journal).

May 3, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

Hidden Words Hidden Worlds: Contemporary Short Stories from Myanmar

Hidden Words Hidden Worlds: Contemporary Short Stories from Myanmar

Edited by Lucas Stewart and Alfred Birnbaum

British Council

ISBN 978-0-86355-877-1

Reviewed by MARTIN KOVAN

I.

Hidden Words Hidden Worlds, an anthology of short fiction from contemporary Myanmar (Burma), is unusual in many senses. It assembles the work of seven established Burmese-language writers, and the same number of newly-discovered voices from a range of ethnic groups, translated by up to thirty literary volunteers into English. Singular not merely in its collaborative breadth, it is unprecedented: it is the first time in a half-century that such an ambitious and eclectic literary undertaking has been able to occur at all.

As well as Burmese, other ethnic groups represented include the Mon, Karen, Kayah, Shan, Kachin, Chin and Rakhine, their writers ranging from “WW2 veterans and rubber tappers to poets and journalists”: aptly eclectic for a document that looks beyond its purely literary status. Yet, Burmese remains the lingua franca of the whole, mediating the translation of the ‘ethnic’ pieces into English, as much as the speech of fictional protagonists (‘He spoke in Burmese, so all would understand him” in “The Right Answer”). Inasmuch as Burmese national hegemony is a frequent theme, it is also built into the production of the text itself.

The textual surface of the stories is thus a literal melting-pot of voices in which something of local lore and linguistic flavour has doubtless been lost from the specifically located original. On the other hand, much of the thematic territory and familiar tropes of ‘the literary’ (love-letters, metaphorical and real moonlight, journeys and partings, fêtes and rendezvous) are in full evidence, a time-warped tropical evocation of something like a 19th-century Russian sensibility. Family visitors meet, try new foods, talk, brood, sightsee, arrange foiled meetings and would-be trysts, and it is often politics that gets in their narrative way.

Stock figures of a Chekhov or Turgenev recur: bachelor uncles, adolescent yearning that discovers disillusion too soon, unmarried young women—not yet spinsters but not always hewing to the traditional social fabric of religious or social rituals of marriage, the fulfilments of family, of Buddhist renunciation, and happy old age. In a Chin variation on the theme (“Takeaway Bride”) young lovers risk separation by her potential marriage, for the dowry’s sake, to an expatriate suitor overseas. A contrasting, less anodyne, tale (“The Poisoned Future”) has an unmarried mother-to-be cast out to live among the socially derelict. Even the great Buddhist boon of being “given a chance to be born a human” proves ironic when, as a drunken grave-digger soliloquizes, “‘Like the saying goes, ‘where walks an ill-fated woman, rain follows.’”

A thematic comparison could also be made with earlier English-language Indian fiction of the feuding family genre (despite the absence in the Burmese context of the great social cartographer of souls in the Hindu caste-system). A prominent theme through-out, unsurprisingly in such an anthology, is ethnicity as such: its richness and divisions. At the heart of these (and another sign of something they share despite difference) are social celebrations that often broach geographic and linguistic frontiers: the famous Thingyan water festival (with its regional variations), local fêtes for unique traditions of music, dance and theatre, spirit rituals, monastic and political ceremonies. Lives from many social strata come together in these as unifying and discriminating at once: ethnic differences potentially erased are also re-defined in their purview (“The Moon…”).

“Reading the Heart” frames the same point in terms of a betrayal of tradition when a growing boy derides, from his own inexperience, efforts to present his local traditions to a national public (his seaside Hsalon village newly crammed with city ‘VIPs’, a term he doesn’t understand) in such a way that the authentic is made fake. But like other figures in these stories of innocence (lost) he only half realises the fact, or only until it is too late to reverse it. Other signalled differences are starkly racial: a darker skin colour signifies (as it tends to generally in South Asia) a lower class which is not just a marker of education or savvy, but also of aesthetic values.

Read in their benign literary contexts, these norms are easy to pass over as an effect of the naïf that runs through the collection in multiple senses: in its simply-limned characters, a plain-spoken style, a fatalism in the face of injustice. But read with the background of recent Burmese history, the fictional surface of disquiet, in this case, is also something which dare not speak its name. Myanmar is a religious-ethnic congeries, but it is curious that no Hindu or Muslim cultural elements feature among these stories. Perhaps another generation has to wait before we can read stories of or from the recently expelled Rohingya Muslim population, whose real sufferings tragically reiterate those so frequently described here as the merciless deus ex machina of the military state: a faceless and unforgiving force that crushes first loves, marriages, literary ambitions and careers, dreams and hopes, underfoot.

For these writers (half of whom are Burmese) racism is not an overt cost of ethnocentrism, so much as a normal condition of tradition that would never think to justify it. Some of the fictions here downplay that condition in the same way a seeming majority of contemporary Burmese (Buddhist) public life does, and the elision of the two would seem to belie the open, national literature to which the anthology as a whole aspires.

II.

Along with a prominence of the carnival, one could suppose that the popular Burmese ‘anything-goes’ vaudeville of performed comic satire (nyeint) might be an irreverent background (of a kind that often sent its practitioners, also, to prison) for the narrative foreground of these contemporary fictions. If any non-Western lifeworld could reproduce the social conditions for the political-satirical flights of a Bulgakov or Kundera, it would have to be modern Myanmar. But here literariness translates often into earnest understatement, as if the fear of the people has for too long dominated their very norms of speech, and writing, as well:

When discussions of religion and community […] strayed into talk of the government, the Abbot would warn everyone: “Stop, stop! The walls have ears.” Then no one dared utter another word. (“The Right Answer”)

The government-cum-military (with its insidiously anonymous intelligence network, or MI) figures as its own personage through-out: all-powerful, deceitful, unfairly extortionate, yet rarely if ever assigned any other symbolic status despite its ubiquitous will to destroy so much of the value the protagonists represent to themselves and the reader of local and national versions of the good and the beautiful.

Even a much-loved local tom-cat is a victim of unknown malefactors (“Silenced Night”), and in Letyar Tun’s self-translated “The Court Martial” it is a disobedient soldier, reflecting on a history of grievous violence for which, in moral if not military terms, he appears on the eve of his retirement likely to pay the highest cost. This story is also rare in giving an individual face, and conscience, to the faceless machine of power, ultimately prey to it, also, for no other reason than power’s indefinite perpetuation:

In black zones, soldiers went “code red”—cruel as sun and fire—though they needed to distance themselves from their targets in order to harden to inhuman purpose.

Plain first-person statement frequently drives narrative with a pervasively plangent tone, born of misgiving or surrender: not yet moral drama, or the classical values of a tragedy waged for a metaphysical truth won. Without overt ideological argument, many of the stories enter into an abstraction of defeat and resignation such that Lay Ko Tin can write (in “The Moon…”), past nostalgia, of his stolen and imprisoned youth that:

Our future was vague, neither black nor white. […] The saying ‘time is the best medicine’ was not true for us […] Maybe the heaviest burden of all was to stay true to our belief that the new regime was false.

The reader sympathises with repeated scenes of incarceration and injustice, without always knowing what stakes drive an absent conflict. It is not so much understood, as enacted, that even a meaningful resistance can sometimes seem to lose even that. Ko Tin’s concluding confession “Yet even now that I’m out, I’ve lost the moon that shone within me” (appearing to belie how literary success has won him subsequent esteem) could stand as a summary metaphor for many of the stories’ protagonists, no matter their ethnic background.

If anything it is literature itself, or even only its idea, that, in being so scarce and valued, is a frequent sole redemption of the worst of deprivations, in both its clandestine consumption and practice. San Lin Tun’s “An Overheated Heart” puts writerliness at self-conscious centre-stage. Where the romanticism of the ethnic stories remains conservative and traditional, this Burmese counterpoint is infected by an urbanity romanticising not literary redemption, but a very modern and ironic appreciation of its capacity to foreclose other fulfilments. One of its pedagogic protagonist’s students reflects on her teacher’s dilemma:

When you write, maybe you compare yourself to other writers, but you can’t […] measure love. Maybe you draw strength from your books, but […] Literature and love are not the same.

Many of the narratives have in stylistic common this mode of realist but understated homiletic, pitched between fiction and memoir, recitative or spoken tale. What often results is a social reportage in which historical events are frequently the pivot around which a minimal fiction turns: little seems invented, as if fiction dare not risk the imagined or possible. When truth-telling is such a prized and dangerous commodity, anything more than verisimilitude might seem profane. A thematic comparison could then finally be made with the European modernist and post-war preoccupation with the police state and paranoia, with Fate and Unreason, the submission and resistance to an impersonal, seemingly baseless power.

In 20th-century Burma, too, if less so since, meaning has been in short supply when speech is curtailed, its expressive powers denied any context in which literature, and life, builds an authentic identity beyond that of ethnicity alone. A malignity in these narratives is pressed by an unspecific Other for seemingly no reason than to make innocents or idealists, or their political exemplars (such as Communists in “The Court Martial”), suffer. Despite reference to Buddhist principles, such as their gothic gloss given by the callow protagonists of “Thus Come, Thus Gone”, religious truism seems unequal to the eeriness of events. “A Flight Path…” negotiates more mundane encounters with a deft obliqueness of address, in which wickedness (figured with regard to the Lord of Death) respects no sacred or profane status quo: “‘When you are the anvil, you must endure the hammer. Am I right?’”

III.

Hidden Word Hidden Worlds marks a hundred-year milestone since the widely-assumed first modern short story was published in 1917 in Yangon (Rangoon) in what was then still British Burma. Its editors stress that while the form existed in the interim through changing literary influences and political fortunes, both modified from the early 1960s by the vagaries of censorial military regimes, it is really only since the fragile transition to democracy in 2012 that a half-century of pre-publication censorship has been formally abolished.

What has resulted in this collection, under the auspices of the British Council, working with surviving local literary and cultural associations through-out the country, traverses formal and rhetorical modes of address, pregnant with a sense of life lived too intensely, or sometimes painfully, to be easily subsumed under one or other literary template. Many of the fourteen stories register intense experience in comparatively traditional modes of nostalgic memoir, stymied youthful romance (with some happy exceptions), or moral confession, in which any resulting incongruity between the telling and the tale perhaps accidentally endows an unadorned form with a force it might otherwise lack.

A number of stories offer graceful homage to oral storytelling (such as “The Love of Ka Nya Maw” and “Kaw Tha Wah the Hunter” to Kayah and Karen traditions, respectively). Yet it is hard to sense, given the thousand year-old generic oral traditions (of soldier-poetry, court dramas, religious tales) how far such old style is transported into a modern English in a way that rehearses, or subverts, their old formulae, much as their sometimes wry irreverence does the political repression that for so long kept idiosyncrasy and experiment from an open literary culture.

The tension between an implicit experimental could-be and the (in the Burmese case, quite literal) safety of the formally familiar is an unspoken feature of the whole. Only an occasional piece (such as “Silenced Night”) is editorially signalled as exemplifying a formal and, in its terms, cultural subversion. Otherwise, a story such as “A Bridge Made from Cord” analogises lost love and the ravages of jade-mine exploitation in an explicit register:

This is what it means to be Kachin and dream of a different tomorrow: a jade bridge crossing over from poverty to a life free from it. I too became a […] prospector of unwashed stones. We all found lots of stones, but almost none of them were jade.

Many of the stories similarly mark a threefold division reflective of the social ones that have seen decades of civil insurgency in the north, north-east and east of the country, between the ethnic Bamar (Burmese-language) majority who still dominate the cultural and political elites, the ‘ethnic’ non-Bamar cultures and languages, and the national (read, Burmese) army which, especially during the long periods of dictatorship (1960s to 1990s) sought to actively diminish both.

“A Pledge of Love…” effectively traverses the geography, and broken loyalties, of all three, figured in the confluence of northern rivers forming the Ayeyarwaddy River, itself dividing the country as the non-aligned narrator is from her lost rebel lover. Only rarely (as in “The Court Martial”) does the fictional frame seek a more objective view of the whole, unless the transfiguring properties of fable (in which heroes overcome, tradition holds firm, and the real is attenuated) perform that function of imagination.

The prospect of a cultural project such as this one was impossible during the many (ongoing) periods of civil war, and during ceasefire too precarious to sustain. The anthology is to be welcome for the fact that seven of these hitherto repressed ethnic identities can now freely be read not only in their own, in some cases formerly outlawed (the Kayah) or otherwise regenerated languages and scripts (the Chin, over a century old; the Mon, one-thousand five hundred years old), and also Burmese, but finally into a 21st-century English, as well.

Times in Myanmar, at least in nascent literary terms, have remarkably changed. Where the eloquence of silence or dissimulation has of course played a powerful role in post-War European resistance to oppression, in Myanmar it has for decades been a literal imperative, and we can’t yet speak fully, even in the expressive terms of national literature(s), of a ‘Burmese thaw’. Hidden Word Hidden Worlds is however a brave and notable first step towards its real possibility.

MARTIN KOVAN is an Australian writer of fiction, non-fiction and poetry. He has lived in Europe and South Asia for long periods, and also pursues academic research in Buddhist ethics, philosophy and religion, including political conditions in Tibet and Burma-Myanmar. In Australia his writing has appeared in Cordite Poetry Review, Island Magazine, Australian Poetry Journal, Westerly, Southerly Journal, Peril Magazine, Mascara Literary Review, and Overland Literary Journal, and in publications in the U.S., France, India, Hong Kong, Thailand, Czech Republic and the U.K.

March 22, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

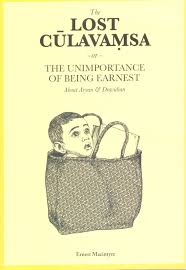

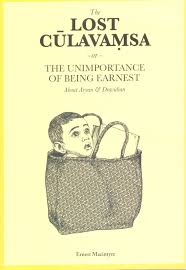

The Lost Culavamsa: or the Unimportance of Being Earnest

The Lost Culavamsa: or the Unimportance of Being Earnest

about Aryan & Dravidian

a play, by Ernest Macintyre

Vigitha Yapa Publications (Colombo, Sri Lanka), 2018

ISBN 978-955-665-319-9

Reviewed by ADAM RAFFEL

In February 2016, in the best traditions of suburban amateur theatre, a group of Sydneysiders of Sri Lankan background performed a play called The Lost Culavamsa (pronounced choo-la-vam-sa) written and directed by fellow thespian and playwright Ernest Macintyre at the Lighthouse Theatre in the grounds of Macquarie University. I had the privilege of co-directing this play as Ernest Macintyre himself was in poor health at the time. I have known the playwright for over 40 years and I was happy to oblige. It was a delightful rewriting of Oscar Wilde’s witty comedy of manners, The Importance of Being Earnest, about late Victorian English snobbery transplanted to an equally snobbish colonial setting in British Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in the 1930s. Ernest Macintyre had created an enjoyable piece of comic theatre about mistaken identity while engaging the audience with deeper questions of ‘race’ and ‘ethnicity’. Macintyre has re-imagined and re-worked Wilde’s play into a satire about the absurdity of racism and communal division. A play for our times and the universality of its theme won’t be lost on audiences who have never heard of Ceylon or Sri Lanka.

However Macintyre is showing a mirror to Sri Lankans in particular. Many of the intricacies and details of the dialogue of The Lost Culavamsa will resonate especially to Sri Lankan audiences just emerging from a 30 year civil war that concluded in 2009. It was nothing short of a national trauma for that island and its inhabitants. At the core of the war was what it is to be a Sri Lankan. The island’s 2500 year written history was deployed by nationalists to justify and push political agendas. The Culavamsa is an ancient Sinhalese chronicle somewhat like the Anglo Saxon Chronicle or Beowulf written in the about the same time in the 7th or 8th century AD, which was the later version of a more ancient Sinhalese chronicle called the Mahavamsa that chronicled the ancient history of the island from the 5th century BC. These were written in poetic form like Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, part history part mythology, and were “weaponised” by nationalists where ancient battles were used as dramatic props in a very 20th and 21st century civil war. Viewed in this context The Lost Culavamsa can be seen as much needed comic relief for a war weary country with a core message of tolerance. Macintyre has deployed the best comic traditions of English theatre to communicate this message to audiences in general and to Sri Lankan audiences in particular. Ironically Macintyre uses the English language in this context not as a symbol of colonial oppression, which it was at one point in Sri Lanka’s history, but as a language of unity and of liberation from the tyranny of ethnic hatred and division. Macintyre shows that English can be a used as a link language between the communities in Sri Lanka, uniting them so they can share their stories. In other words English can be appropriated as a Sri Lankan language. So Macintyre sets his play in the late afternoon of the British Empire as a means to communicate to Sri Lankans how they once were and not to feel ashamed or nostalgic but to learn and accept that colonialism changed the country forever and in Lady Panabokka’s words (the character based on Lady Bracknell) “that humans go forward, not backwards and whether the British Empire lasts or not, it is a stage in the forward motion of civilization”.

These lines uttered by Lady Panabokka underline Macintyre’s view that history cannot be undone. Whether Sri Lankans like it or not colonialism was a historical reality and now forms an integral part of its history. Any attempt to wipe it out is not only futile but dangerous. It is a progressive view of independent Ceylon that drew upon the playwright’s own extensive experience in Sri Lankan theatre and the arts in the 1950s and 1960s. This was a period in the island’s history where artists, writers, dramatists, musicians, historians and architects of the English speaking elite (of which Macintyre and my parents were a part) were engaging with local Sinhalese and Tamil speaking artists in an attempt to construct a national “Sri Lankan” identity and vernacular culture that drew upon the best of European, Indian, other Asian and local Sri Lankan traditions. The milieu, in which Macintyre acted, directed and wrote in his youth and early adulthood still has a profound influence on his world view that a nation state consists of multiple nationalities, faiths and communities and should have a national artistic culture that draws upon its local multiple traditions while being nourished by international artistic influences including that of the country’s former colonial rulers. The fact that one can place Macintyre in the English / Australian theatrical tradition as well as in the Sri Lankan one is something that he is very comfortable with. An example of this is the first play he wrote in Australia in the 1970s called Let’s Give Them Curry a comedy about an immigrant Sri Lankan family in suburban Australia. Both Australia and Sri Lanka view that play as a part of their own theatrical repertoires. Unfortunately Let’s Give Them Curry was his first and only play that dealt with Australia. For in 1983 his world was turned upside down. The community he belonged to in Sri Lanka; the Tamils suffered a series of state sponsored pogroms where they and their property were systematically attacked by chauvinistic Sinhalese Buddhist mobs. Thousands were killed and the trajectory of the country changed forever. This affected Ernest Macintyre personally as he saw many close friends and family lose their lives and livelihoods. He used his vantage point in Australia to comment on the idiocy and futility of the endless cycle of violence in the land of his birth with a series of plays he wrote starting in 1984 and continuing to the present day. Macintyre drew upon his favourites of the Western theatrical canon – Sophocles, Shakespeare, Brecht, Beckett, Arthur Miller, Edward Albee, Shaw and Oscar Wilde to write satires, tragedies and comedies dealing with the subject of communal violence in Sri Lanka in order to have a wider conversation about identity. The Lost Culavamsa is the latest in that series.

The Ceylonese (Sri Lankan) characters in The Lost Culavamsa are a carbon copy of Wilde’s English characters in The Importance of Being Earnest. These Ceylonese characters also speak an English redolent of the Edwardian England of Wilde himself. They illustrate the extent of British influence amongst the local Ceylonese elite in the 1930s. These elites were loyal to the British Empire where the sun was about to set very rapidly. The Ceylonese upper bourgeoisie, however, thought that their world of tea, whiskey, cricket, bridge and tennis would last forever. Many of them thought that they were brown Englishmen and women consuming Shakespeare, Milton and Dickens treating these icons of English high art as their own and dismissing with contempt any attempt by local Sinhalese or Tamil speakers to re-write and translate works from the European literary canon. To them Ceylon was a little England where the general population was, at best, an endless supply of domestic servants and workers to toil in their estates and at worst something inconvenient to put up with. This exchange between Lady Muriel Panabokka and James Keethaponcalan (mimicking the famous ‘interrogation’ scene in the Importance of Being Earnest where Lady Bracknell interrogates Jack Worthing as to his suitability to marry her niece Gwendolyn Fairfax) illustrates the point:

Lady Panabokka: A formal proposal of marriage shall be conducted properly in the presence of the parents of both parties, Sir Desmond and I and your two parents. However, that is not on the cards, at all, till my preliminary investigations are satisfactorily completed.

(Lady Panabokka sits)

Ernest, please be seated. Let me begin.

James: I prefer to stand.

(He stands facing Lady Panabokka. She takes out a notebook and a pencil from her bag)

Lady Panabokka: Some questions I have had prepared for some time. In fact this set of questions has evolved, at our social level, as a standard format of precaution, for our daughters and our social level. First, are you in any way involved in this so called peaceful movement for eventual independence from the British?

James: It doesn’t bother me, Lady Panabokka, I’m happy with the status quo, the British Empire……

Lady Panabokka: Excellent.

James: But I have been made to think about it, sometimes…

Lady Panabokka: What is there to think about it?

James: That we have to lead….. double lives…..

Lady Panabokka: What is that?

James: Like, my name is Ernest, but also Keethaponcalan

Lady Panabokka: So?

James: Ernest is from the British Empire, Keethaponcalan from the native Tamil culture, something like a …a double life…..

Lady Panabokka: Where do you get such confused ideas from?

James: From a scholar I know well……I was told that sometime or other the British Empire will be no more and we will all have to think of our own historical origins….

Lady Panabokka: How far back do we have to go? To when we were apes? Before we were Sinhalese or Tamil we were all apes, hanging on the same tree and chattering the same sounds! Tell your scholar, obsessed with the past, that humans go forward, not backwards and whether the British Empire lasts or not, it is a stage in the forward motion of civilization….

James: Never thought of it like that….

Lady Panabokka: So many things you “never thought of it like that”. And there is the practical problem of the Indians. My husband Sir Desmond thinks our only real protection from the Indians is to be in the firm embrace of the British Empire. And the Indian idea that we are of the same stock was put to the test when Sir Desmond had to visit India recently for a Bridge tournament and found that the supposedly bridging language between them and us, English, was subjected to such outlandish accents, that the game took sudden wayward turns, the way the Indian accents misled the Ceylonese.

James: Yes, I have heard that they don’t speak English like us.

Lady Panabokka: Now, what may be, a related question. Do you speak Sinhalese?

James: I’m well educated in Tamil and speak it fluently

Lady Panabokka: That is an unnecessary distraction, I asked you about Sin Halese

James: Sin Halese……well, sort of, yes, to deal with the general population and…..

Lady Panabokka: That’s why I asked, because (with a sigh) the general population will always be with us. There is no harm, though, in knowing some Sin Halese oneself, for its own sake, but one must not carry it too far.

James: Too far?

Lady Panabokka: Yes, I don’t think you have heard of this man called Sara Chch Andra, a strange name even for a Sin Halese….

James: No, I have not heard….

Lady Panabokka: I’m glad. He should remain unheard of

James: Why?

Lady Panabokka: You know, Oscar Wilde’s “The Importance of Being Earnest”?

James: I love it, I played Lady Bracknell in school!

Lady Panabokka: It is one of our beloved plays, and this man, Sara Chch Andra has debased it by re- writing it, in Sin Halese, as “Hangi Hora” [Hidden Thief], whatever that means!

James: Really?

Lady Panabokka: Yes, I got it from Professor Lyn Ludowyk. Lyn was at Sir Herbert Stanley’s garden party at Queens House yesterday, and he actually spoke about it approvingly. Sometimes I really can’t understand Lyn….why can’t these people write their own plays and not rewrite ours!

The comic irony of the line “why can’t these people write their own plays and not rewrite ours” won’t be lost on a Sri Lankan audience. Lady Panabokka who is an English speaking Sinhalese sees no problem with The Importance of Being Earnest as “her play” and by “these people” she means the Sinhalese speaking writers who should be writing “their own plays”. She sees herself as quintessentially English who would have graciously accepted the fact that she would not be allowed into the Colombo Club which was an exclusively whites-only club for English civil servants and administrators. Lady Panabokka, like Lady Bracknell, sees the world as a hierarchy where everyone has their allocated place, which they should accept with grace and dignity. As Macintyre says in his introduction to his play:

So Lady Panabokka establishes early in the play, that … like Lady Bracknell, … her belief that what matters in life is social status and class. Even race maybe ignored where class prevails as it happens with many Colombo “upper class” young people, Sinhalese and Tamils …

Lady Panabokka who “supervises” this whole improbable comedy is the most identifiable of Oscar Wilde’s characters, the famous Lady Bracknell. She is transplanted. The whole plot, except for the meaning of ethnicity in Lanka which makes it a different play, is transplanted Oscar Wilde, with the colours, hues and texture of the plant growing naturally from the soil of British Ceylon.

In the final Third Act of The Importance of Being Earnest the relatively minor character of Miss Prism exposes the real identities of Algernon Moncrieff and Jack Worthing to their respective love interests Cecily Cardew and Gwendolyn Fairfax. In Wilde’s play Miss Prism locates the lost handbag in which she left the baby Jack Worthing twenty years earlier. In The Lost Culavamsa the point of departure from Wilde lies in how Pamela Mendivitharna unveils the identities of Danton Walgampaya and James Keethaponcalan to their respective love interests Sridevi Kadirgamanathan and Gwendolyn Panabokka.

Macintyre has transformed Miss Prism’s character Pamela Mendivitharna to a major role on a par with Lady Panabokka (the Lady Bracknell character). Pamela is a scholar who lost the baby James in Colombo in a malla (a shopping bag made of treated palm leaves) together with a copy of the Culavamsa. She was a governess to this baby James whose biological mother was Lady Muriel Panabokka’s sister and also Danton Walgampaya’s mother who was Sinhalese (Aryan). Pamela lived with baby James’s parents while pursuing her research into the ancient history of the Aryans and Dravidians in Sri Lanka, which was also a popular pastime of British civil servants and orientalists in Ceylon during that period. Baby James was found by a Jaffna Tamil couple Sir Kandiah and Lady Keethaponcalan and adopted him as their own in a Tamil (Dravidian) environment. Pamela eventually traced baby James to Jaffna and found employment with the Keethaponcalans as James’s nanny. As Macintyre says in his introduction:

Why in this story is there a copy of the Culavamsa … also inside the malla with the baby? The Culavamsa’s part in the play is to link up this story with, arguably, character as big and important to the story … Pamela Mendivitharna, the lady who was responsible for the baby in her paid care …

While this baby [James] born into a Sinhalese family grows up as a Tamil, Pamela Mendivitharna … begins to doubt the well-held belief of the time [1930s] … that the ethnicities of Ceylon [Sri Lanka] resulted from North Indian Aryans settling in the island and South Indian Dravidians coming to the island as a different “race”.

The final denouement of the play ends just as Wilde’s. The only difference being Pamela’s explanation to the audience that the two blood brothers were brought up in different environments and each displaying the characteristics of the environment in which they were brought up. Her study of the Culavamsa was crucial in her realisation that “our ethnicities reveal social attributes, not biological differences.” This is where Macintyre uses Wilde’s structure to expose the fallacy of ‘race’ as an exclusively biological characteristic. The ancient chroniclers and poets of the Culavamsa mention different groups or tribes or nationalities but they could not have had any idea of the very modern and European scientific and biological concept of ‘race’. Macintyre’s play is set in the 1930s, a time when Eugenics and the pseudo-science of Social Darwinism were prevalent in Europe and United States in order to legitimise the odious narrative of white European supremacy. This sort of thinking also influenced some South Asian nationalists during that time as they appropriated these European pseudo-sciences to construct their equally odious narratives of their own national origins. Later on this would have deadly consequences in the rise of fascism and communal violence in Europe and Asia.

Macintyre, however, never loses focus that this play is essentially a romantic comedy. His close following of Wilde’s structure and characters in The Importance of Being Earnest makes viewing and reading Ernest Macintyre’s The Lost Culavamsa an enjoyable experience. Macintyre has transplanted all of Wilde’s minor characters including Reverend Chasuble who is re-created as Reverend Abraham Pachamuttu, the servant Lane as Seyadu Suleiman and the butler Merriman as Albert. As with all great comedies whether it be the films of Charlie Chaplin or Luis Bunuel or the plays of Oscar Wilde or George Bernard Shaw there is always an undercurrent of seriousness and even tragedy. The Lost Culavamsa is, in my mind, no different.

ADAM RAFFEL is a Sydney poet and writer.

March 1, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

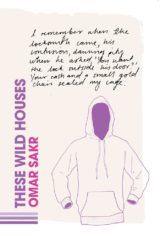

These Wild Houses

These Wild Houses

by Omar Sakr

Cordite Press

ISBN: 9780975249277

Reviewed by BEN HESSION

In a departure from most poetry books, the series issued by Cordite Publishing features a preface by the poet, as well as an introduction by an established writer, who in Omar Sakr’s case is his mentor and tutor, Judith Beveridge. Unlike the prefaces of the other poets in the Cordite catalogue, Sakr does not delve into overarching literary or philosophical theory about the ensuing text. Rather, Sakr speaks of life experience, observation ‘It is a statement – an exploration of me and what I’ve seen.’ (xi) Indeed, compared to the other writers, it would be easy to judge Sakr as something of a naïf. But this would be to deny his real ability as a poet, which, in These Wild Houses, sees a disarming honesty matched by an acuity of poise, nuance and craftsmanship.

Sakr’s collection opens with a quote from the prominent literary critic, James Wood, who in an interview with literary website electricliterature.com, speculated that in a society without religion and a belief in immortality, that not even houses would remain, since through the death of their occupants they would remain unattended. Houses, in the collection, have many structures, some physical others figurative, but each able to induce a real response. Aptly, the first poem in the collection is ‘Door Open’ which both suggests a threshold and a chance to view the interior. Towards this end, Sakr use of enjambment breaks open sentences to reveal something very human and even sensual:

Wild houses we

live in licked brick & sun

warmed stones, in grass blood mortar

and flesh. Listen up the halls, be careful (3)

later he invites the reader to “Come inside, let me/ warm you with all I am. Mind your head/ here on the ridges of my teeth.” (3)

‘All My Names’ demonstrates that “these houses” can be the nicknames one acquires, but are less than comfortable to live inside, which become the reciprocating metaphors for McMansions and housing commission homes which people must also live within, leaving scars.

An almost prosaic rhythm pervades much of the poetry in These Wild Houses, lend a sense of the unaffected or the low-rise ease of suburban living. Suburbia, despite this apparent sensibility is also a contested space, and Sakr’s choice of rhythm serves to make pellucid the innate tensions that arise. In ‘Here is the Poem You Demand’, for example, Sakr provides a list of identity markers one might expect from a ‘queer Muslim Arab Australian from Western Sydney’ that is both a strident affirmation of lived experience, as we see in

Here is the uncouth domestic abuse & plasma televisions,

the marbled fruit of my skin. (4)

and we also see in

Here is the mosque you despise, minarets pinked

by sky. Never forget it in the foreground (4)

and an ironic statement on alterity as a source of stereotyping or tokenistic spectacle, being on demand by the reader, who might not empathise with the sense of pain or struggle that comes with that experience and its articulation

Here is the noose I hang myself with

every day. Here is the blade I trust will sever it. (4)

The couplets in this poem show Sakr’s ability to distil of his world and journeys within it into economical lyric poetry. In ‘Dear Mama’ the longer lines ensconce the prosaic feeling, as they navigate the casual extremes of the poet’s upbringing. The second stanza notes:

Your god is capricious, strikes no reason, some days (the hours

you had full gear, I later found) you’d grin and order us a pizza

in and we’d lounge about our smoky temple as your silver screen

apostles entertained us, shot & bled & fucked & spat & died

for us. Those days were the best. Others were nails-on-chalkboard (6)

Sakr then details the abuse he received from his mother, and it is here that the restraint inherent to his lyricism perhaps becomes the most salient. In stanza three, motivation is stated succinctly:

You saw my treacherous father in the closet of my skin, my face

his imprinted sin. (6)

The line break serves as emphasis, taking over from words themselves. Economy heightens the severity of the abuse and the strength of the poet’s own resilience later in the stanza:

I remember when the locksmith came, his confusion, dawning

pity when he asked, ‘You want the lock outside his door?’ Your cash

and a small gold chain sealed my cage. How could you think walls

would hold me? If you knew how I made that cell a world, hard

but free, you might refashion yours: a hundred books, each one key. (7)

The enjambment and the use of the isolated line in ‘Harmony of Dirt’ allows a treatment of death that is not overwhelmed by the distraction of emotion, allowing rather to reader again to share in loss and its unspoken profundity:

All around him a circle of bearded men stood confronted

with finality, a father with son,

a cousin, with cousin, life with echoes.

His funeral made a Friday morning (54)

This poem marks the deep bonds Sakr has with family despite the abuse depicted in ‘Dear Mama’. Identity, as defined through relatives or community is fraught with various tensions throughout These Wild Houses. Identity for Sakr is Lebanese Australian, a hybrid of two distinct cultures that is constantly renegotiating itself. In These Wild Houses, Sakr is mapping its landscape. ‘Landing’ notes the children growing into forgetting the Arabic of their parents and grant parents; ‘ghosting the ghetto’, meanwhile, sees a sort of ersatz hajj taken to Warwick Farm in the Australian made vehicle, the Holden Commodore.

‘Call Off Duty’, examines the anxieties anticipating the poet’s coming out to a brother, who appears to be consumed by the virtual machismo of video game warfare. By implication, this might reinforce an incumbent, culturally conservative and exclusively heteronormative view of masculinity. However, the acceptance by his brother of his sexuality – besides offering relief – also displays apparently changing attitudes within the Lebanese Australian community.

‘Botany Bay’, takes suburbia as contested space to another level – but not without humour -where Muslim Arab Australians picnic adjacent to a museum for Captain Cook, the bringer of British colonization over Aboriginal land. The poem challenges the resulting marginalization, particularly towards his, own, Muslim Arabic community, with the narrator musing over a clash between the older Anglo hegemonic orthodoxy and the newer assertion of a multicultural cosmos, with its “hijabbed sky”. (17)

‘The H Word’, which was included in Puncher and Wattman’s ‘Contemporary Australian Poetry’ anthology, again demonstrates the power of restraint shown in Sakr’s other poems. As the “H” of the title is an initial to undercut expectations as it is to help trigger signifiers. “Home” for instance, is scarier than horror or homicide; whilst “a little H” is the italicised cry for help rather than the escape offered by what might have been inferred, heroin. The main “H” word, “hood”, and its variants, is a pun on the hip-hop abbreviation of neighbourhood, with one being emblematic or stereotypical of the other. As clothing it serves as a sanctuary from the straits of the narrator’s environment. Importantly, whilst Sakr is often explicit about his background and his feelings are clear, he indulges neither self-pity nor street-wise bravado. We see, instead, the strength of silence through the spaces between the couplets, which, in turn, endow both measure and powerful nuance to the poem, particularly in its concluding lines, expressing what he would see in death:

I expect to look down and discover in my chest

A hooded heart, lying heavy and still. (11)

While many of the poems in These Wild Houses are definitely gritty, the aim is not for a prescriptive aesthetic for Sakr. Rather, it serves to establish the profound authenticity of the poet, something which we see he takes to the United States in ‘America, You Sexy Fuck’ and ‘A Familiar Song’. In the latter poem, his situation creates empathy for the beggars around him. The nature of what Sakr has explores in the collection is probably best summed up in its closing piece, ‘A Biographer’s Note’ where he rhetorically asks the reader:

what is tragedy and how might it play

to see a life where we now recoil

from the stink of desperation? (58)

These Wild Houses has shown that Sakr has tamed the more formal aspects of poetry, rendering the extremes of his past and their attendant, potentially distracting, emotions is no easy feat. As a debut collection, it holds great promise for a relatively young poet. The recognition of his talent is evidenced by being a runner-up in the Judith Wright Poetry Prize and his appointment as the Poetry Editor of The Lifted Brow. Judith Beveridge, in her introduction, describes Sakr’s debut as” impressive” and says that it “announces a new and important voice to Australian poetry.” (xiv) He has invited us into his houses, most certainly, but now he has made us, his reader-guests, hungry.

References:

Paulson, Steve. ‘The Art of Persuasion, an Interview with Critic James Wood’, electricliterature.com, 1 July 2015.

BEN HESSION is a Wollongong-based writer. His poetry has been published in Eureka Street, International Chinese Language Forum, Cordite, and Can I Tell You A Secret?, the Don Bank Live Poets anthology. Ben’s poem, ‘A Song of Numbers’, was shortlisted for the 2013 Australian Poetry Science Poetry …

January 23, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

Can You Tolerate This

Can You Tolerate This

by Ashleigh Young

Giramondo

ISBN : 9781925336443

Reviewed by MARTIN EDMOND

Can You Tolerate This? is a collection of twenty-one personal essays on a variety of seemingly disparate subjects; some just a few hundred words long; others more than thirty pages. All are highly accomplished, both stylistically and in terms of the use they make of their author’s existential, experiential and other concerns. They are also, in way that is subtle to the point of subversion, very amusing; but it is a painful kind of humour, reminiscent of the paroxysm of pain we may feel when we bang our elbow on some hard surface like a wall or a door or the arm of a chair, and activate our funny-bone.

Bones are in fact where the collection begins, with a short account of the life of an American boy who suffered from a rare disease which caused another skeleton slowly to grow around his original one. This introduces a major theme of the collection, its examination of the complexity of the mind-body relationship, using a variety of curious examples from the world but mainly employing the author herself, her defaults and her daily activities, the various milieu in which she moves, as a subject for speculation—often of a rather fraught kind; but therein, as I said, lies the humour.

So this is the first point to make: although the book may seem to be a collection of disparate pieces, it is in fact a highly wrought artefact, as unified as any good novel or memoir may be; in fact, better unified than most. One of these unifying factors is the body / soul dynamic, mentioned above, wherein the author inquires into her own condition, or habits, in such as a way as to try, not so much to explain them, as to escape from some of their more oppressive effects. Here, through a curious alchemy, the compassion which she shows to others, like her dying chiropractor (in the title piece) is somehow, perhaps by means of the excellence of her style, extended to herself—and by analogy to her readers, who will recognise in the author’s predicaments the ghosts of their own.

This kind of ‘therapeutic’ writing can, in less assured hands, come across as awkward, self-serving or even self-pitying; but not in this case. Ashleigh Young’s voice is bracing and illuminating; although she is often tentative, sometimes almost to the point of hyper-sensitivity, she is always honest; and these are the qualities—honesty, illumination, vigour, sensitivity—that make the collection so beguiling. Whether she is practicing yoga, going for a bike ride, adjusting her breathing to the demands of cycling or running, as a reader you experience a feeling of rare empathy with the authorial voice.

So her self-portrait, or rather her succession of self-portraits, is entirely successful. In part this is because of another, and deeper, unifying aspect to the collection: deftly, without ever really seeming to try, almost by stealth, Can You Tolerate This? is also a portrait of the author’s family and, as a consequence, an account of her growing up in the small town of Te Kuiti in New Zealand’s North Island, with some holiday sojourns at Oamaru in the South. As the book proceeds, especially through its longer essays, we come to know her family—her father and mother, her two older brothers, herself, various family pets—almost as well as we may know our own. This splendid family portrait is achieved without recourse to whimsy, cuteness, or special pleading; most of what we see is far too raw, and too real, for that. In some respects this is the most remarkable aspect of a very remarkable book.

The long essay, ‘Big Red’, for example, is almost unbearably tense to read because of the sense of risk expressed in its account of the erratic career of Ashleigh’s much-loved older brother JP (who calls her ‘Eyelash’); that something untoward might happen to him, though in fact nothing does, gives the essay the character of a thriller. Moreover, and this is an example of how highly wrought this collection is, that feeling of incipient dread does pay off, much later in the book, in the catastrophe which afflicts the other, the elder brother, Neil, by now living in London. I won’t, of course, say what that is.

The father, with his benign eccentricities, his obsession with flight, his odd remarks; the mother, too, in her attempts, for example, to banish from mirrors the reflections of all those who have ever looked into them, become as vivid as the two brothers. The account of the mother’s writing life, which, in the piece called ‘Lark’, concludes the collection, accomplishes something almost unprecedented: a merging of voices, in which we become unsure if we are reading the mother’s writing or the daughter’s redaction of it. This is, apart from being a stylistic tour de force, an example of familial love raised to a higher power—and brings the book to a winning, if poignant, close.

Like its thematics, the book’s writing proceeds by indirection. Young’s prose style seems relatively straightforward, unornamented or only lightly ornamented; yet her sinuous, seductive sentences take us, almost inadvertently, into very strange places indeed. Witness, for example, her digression upon women’s body hair (‘Wolf Man’, p. 138) which begins: My moustache was negligible in comparison to the hair on the faces of these women and ends The discomfort grows from within, as if it had its own dermis, epidermis, follicles. This is because she is, as a writer, incapable of dishonesty—neither the larger sort which invents in order to cover up, or divert attention from, uncomfortable things; nor the smaller kind which prefers something well said to something, perhaps painfully, or hilariously, true.

This is a brave, sometimes confronting, always intriguing, often compelling, and distinctly unusual book. The essays are consistently entertaining in a way that is rare in literary non-fiction of any kind. The voice is one which readers will fall in love with; they will actively wish for the author to succeed in her life’s endeavours; while recognising that success may be an impossible goal; or, at the very least, a goal impossible to measure. They will feel the same way about the wonderfully eccentric, though entirely typical, Young family, right down to the miniature dachshund with the back problem.

A warning for Australian readers: Ashleigh Young is a New Zealander and her book, republished by Giramondo in the Southern Latitudes series, with a stunning cover by Jon Campbell, originally came out in 2016 from Victoria University Press in Wellington. Ashleigh Young won, along with Yankunytjatjara / Kokatha poet Ali Cobby Eckermann, also a Giramondo author, one of eight coveted Yale University’s Windham-Campbell Prizes, worth $US165,000, awarded in 2017. But that may not be enough to banish the instinctive, almost visceral, disregard most Australian readers have for works from across the Tasman; as if nothing that comes from there could ever rival the terror and the grandeur the best Australian writers are able to command. Nor the inadvertence and obtuseness of the worst.

I don’t quite know what to say about this ingrained prejudice. As a New Zealander myself, albeit one who has lived nearly forty years in Australia, I have never yet been able to compose (it is not for the want of trying) the aphorism that would encapsulate, and so detonate, this unwillingness to engage with a close neighbour. I think that the domestic economy in Aotearoa may be so fundamentally different from the one here that Australians cannot go there. I mean it is so tender and so violent, so intimate and so alienated, so intricately genealogical, that to do so would risk a vastation.

Ultimately, perhaps the problem is the accommodation, however imperfect, between indigenes and settlers that Aotearoans have embarked upon, which remains as yet unattempted here. This of course opens up another interpretation of Ashleigh Young’s title; as if it might be addressed to all the nay-sayers among us who might instinctively resile from a book that comes from so far away, and yet so near at hand, as Te Kuiti. But it also augments the original meaning: some kind of fundamental readjustment of skeletal, no less than existential, or even spiritual, structures might result. It might even be the intention. Can you tolerate this? You could try.

MARTIN EDMOND was born in Ohakune, New Zealand and has lived in Sydney since 1981. He is the author of a number of works of non-fiction including, Dark Night : Walking with McCahon (2011). His dual biography Battarbee & Namatjira was published in October 2014.

December 16, 2017 / mascara / 0 Comments

Blindness and Rage: A Phantasmagoria

Blindness and Rage: A Phantasmagoria

by Brian Castro

Giramondo Publishing

224pp, $26.95

ISBN 978-1-925336-22-1

Reviewed by JOSEPH CUMMINS

Brian Castro’s eleventh work of fiction is a profoundly playful novel about life, death and authorship. Faced with a terminal diagnosis, Lucien Gracq contemplates the meaning and meaninglessness of life as a town planner. Given fifty-three days to live – this is an allusion to Georges Perec’s novel 53 Days, which he left incomplete at his death – Gracq decides to focus on finishing his epic poem, Paidia. He moves to Paris and there joins an absurdly shadowy society of misfit intellectuals. Who wouldn’t be intrigued by this?

This is not an advertisement for euthanasia. We welcome those with a terminal illness who are interested in the test of time, who think hard about sacrifice and the culture of intellectual legacies. Members will, through an act of law, erase their name and bequeath their work to a living other. It is plagiarism in reverse we practice, to provide a cleansing service before oblivion. We are Le club des fugitives. (20)

A highly literate kind of gallows humour infuses Castro’s novel in perhaps the most concentrated doses of his oeuvre. Here it is harnessed to his concerns with the erasure of the self and the attempt to retain some sort of life beyond death, lenses that Castro often equips to view these universal questions. ‘What does it mean / if not pure and present vanity / to think of your memory / as a future commodity?’ (21), Gracq asks, scornful. Subtitled ‘A novel in thirty-four cantos’, this short novel is written in mostly free verse.

Using the brevity and concentration of verse, Castro thinks on life, death, the poetic body – the body that is created by poetic language – in terms of play. He is intent on wringing every last drop of poetic and philosophical potential out of this concept. We follow our poet planner Gracq as he dances with the play of death, grapples with the play of authorship, messes with the play of quotation, shimmies around the play of the imagination, and slides between play and meaning. Gracq theorises that ‘It is catachresis – the crossing over / which extends life; gives shards of signs / a shiny meaning, pure illusion, / a reality or just a game of cards’ (131). After sending drafts of his epic poem to the leader of the Fugitives, George Crepes (an anagram of Perec?), Lucien receives a playful critique:

Your Paidia is losing its serious play,

verging on frivolity. There is no crossword

or chiasmus, no game of Go.

There is no verbal Rubik’s Cube

or even rubrics cubed; no red lining,

no rules, injunctions, prescriptions.

The word I say to you is No

do not go down this tube of mining

your emotions at this late stage.

Your heart is thumping out the words;

there are so few beats left to submit. (123-4)

The beats of the heart measure both life and poetic tension and release. The examination of a poetic body – ‘your body is your life / a work in progress’ (39) – particularly the way Castro looks back and forth at poetry and the process of aging, one through the other, is perhaps the aspect of this novel that struck me as its most consistently serious statement.

Always attuned to the experience and implications of being in and out of place, one of the most entertaining aspects of Blindness and Rage is the constant and ever-more farcical shifts between the Adelaide, Paris, and a constellation of other locations, including Hong Kong and Dubbo (in western New South Wales). I particularly enjoyed the juxtaposition between Adelaide and Paris – ‘For a long time, Lucien used to go to bed early / thinking fantasy oh, fantasy! / He had become too staid – / perhaps it was living in Adelaide’ (60). This allusion to the opening line of Proust’s masterpiece is quite hilariously subverted in the next line: ‘Where is my fantasy? / He shoved a DVD of Sex and the City / into the player but it did nothing / to divert the hurly-burly’ (60). Later the comedy continues as the Australian obsession with sport is mythically mocked: Gracq ‘was from the South, / some say it is a barbarous place / whose only activity is sport; / perhaps it is like Sparta’ (162).

But aside from these amusements, the sharp relief between centre and margin also produces sincere and poignant meditations on memory. Transported to the Western Plains Zoo in Dubbo – and I thought Adelaide was a long way from Paris – we encounter the unique moments of pathos that for me marks Castro’s work.

…knowing how years hence you would be sorry how quaint all your promises were, how you knew well the passions of others and decided you were not the sort to treat them lightly, how you remembered the past incorrectly, conflating your own experience with that you had read, in wonderment, and ultimately, in forgetting. (180)

Skipping in an and out of the shining auras of works such as Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, the love letters of Kafka, and with a soundtrack of Chopin, Blindness and Rage is as virtuosic as it is opaque. Cheeky references spring up on almost every page – I noticed numerous reworkings of Proust’s famous opening line – ‘he was in search of lost emotion – / words which slowed the heart and / humoured the day and held / the night with chimeras’ (2) – but that is probably because I am most familiar with that work. Castro’s writing is nimble and at times resonant, but the relentless allusion to a wide range of writers, philosophers (and pornographers) can at times stifle ones enjoyment. Of course Castro the modernist wants us to work for it – he’s playing with expectations about meaning, difficulty and the labour (and pleasure) of reading.

While it is Castro’s first verse novel, the playfulness at the core of Blindness and Rage links it closely to much of his oeuvre. Despite his early doubts about writing and the commodification of memory – and following the hijinks of his time with the Fugitives, a love affair with his neighbour in Paris, and many half-blind alleys of mischievous reference – I feel like Gracq ends up reaching a conclusion that rings an uncannily familiar note to Castro’s masterwork Shanghai Dancing: ‘To be able to write is not to say anything / but to put small things together, / shards which once cut into memory, / made up of roots and calligraphy’ (196). While seemingly far removed from the territory covered in the ‘fictional autobiography’ Shanghai Dancing, Castro’s latest offering continues to map the space between memory, place and creativity. It may confound, but Blindness and Rage is just as rewarding.

JOSEPH CUMMINS writes about contemporary Australian literature and popular music. His first book (with Ashley Barnwell) Reckoning with the Past: Family Historiographies in Postcolonial Australian Literature, will be published in 2018.

December 12, 2017 / mascara / 0 Comments

Seabirds Crying in the Harbour Dark

Seabirds Crying in the Harbour Dark

by Catherine Cole

ISBN 9781742589503

UWA Publishing

Reviewed by CAROLINE VAN DE POL