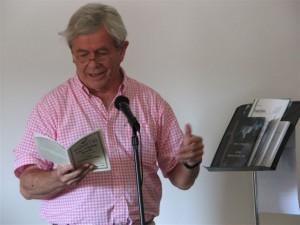

Chris Wallace-Crabbe

Chris Wallace-Crabbe is an octogenarian metaphysician whose generous accolades include participating in a reading series with Iraqi poets Fadeel Kayat, Jamal Al-Hallaq, Sudanese poet Afeif Ismail, and Chilean poet Juan Garrido-Salgado. Thereafter, he was anthologised in a ground-breaking transnational collection, Poetry Without Borders Ed Michelle Cahill (Picaro, 2008). Having conferenced with the legendary likes of Andrew Motion, Alastair Niven as well as Mulk Raj Anand, Kamala Das, Raja Rao, Eunice de Souza, G.V Desani and Raj Parthasarathi, he describes himself as a post-colonialist with history being the ultimate arbiter. Carcanet published his New and Selected, while his latest collection is My Feet Are Hungry (Pitt St Poetry) and Afternoon in the Central Nervous System is forthcoming with Braziller, New York.

Chris Wallace-Crabbe is an octogenarian metaphysician whose generous accolades include participating in a reading series with Iraqi poets Fadeel Kayat, Jamal Al-Hallaq, Sudanese poet Afeif Ismail, and Chilean poet Juan Garrido-Salgado. Thereafter, he was anthologised in a ground-breaking transnational collection, Poetry Without Borders Ed Michelle Cahill (Picaro, 2008). Having conferenced with the legendary likes of Andrew Motion, Alastair Niven as well as Mulk Raj Anand, Kamala Das, Raja Rao, Eunice de Souza, G.V Desani and Raj Parthasarathi, he describes himself as a post-colonialist with history being the ultimate arbiter. Carcanet published his New and Selected, while his latest collection is My Feet Are Hungry (Pitt St Poetry) and Afternoon in the Central Nervous System is forthcoming with Braziller, New York.

Cardamom Country

Well, yes, I’ve always been intoxicated by India,

a rich Everywhere which can’t possibly resemble us

(except in playing cricket, either straight or bent),

let alone the notorious gravity of beer-drowning Belgium and Wales,

being a technicoloured macro-country of hill station and spice

plus devilmaycare characters like Babur and Kimball O’Hara

and at best reminds me of every adventure I relish,

not excluding the nursery land of green ginger which

may well have been Cathay.

It could be that India is a collective subconscious,

but I can let that one go through to the ‘keeper

tricked out in glorious silks and golden bangles.

My dad lived there through years of war;

I love the way they sustain the English language,

though why we call it that only the Krauts will know,

(bespectacled, growing esteem among literate historians);

a tongue that tricked wryly past Norman bastardisation

holding hands with a lovely Latin of inkhorn learning

in order to produce dinky-di oxbridge Australian

or laboured essay prose from catholic schools,

but which in their spicy landscape is melodiously

delivered from high up the oral register.

On my very first visit to those curried shores

I flicked my passport open to an inclining clerk

who cut to the paper chase quickly and demanded,

“Who is the greatest English poet?” and when

I roundly demurred at Shelley, proffering Shakespeare,

He could cope with that, riposting blandly,

“He was not for England , but for all mankind”.

He passed me on to the dodgy taxi-drivers, Hanuman

and Petrolpants, into the southerly smileage of Madras

with pluncake in Spencer’s emporium.

Back in those days even when the street beggars laughed

and our hotel drummer wanted to eat the cook; no,

it was the other way round, like sari-bright India:

that bulky chef was devoured of all. Whatever

passed by meltingly became him: or her.

and I suffered only once from Akbar’s Curse,

but that was in a posh quarter of Delhi,

not on the elephantine Great Trunk Road

in some lean-to-café with hot sugary tea.

I filled the shower with shit for a couple of days.

Trivandrum was another story again,

literate, breeze-laved, anticipated from childhood,

a southwest version of rapture’s roadway far,

while necklaced with glinting lagoons.

(2012)