Joseph Cummins reviews Blindness and Rage: A Phantasmagoria by Brian Castro

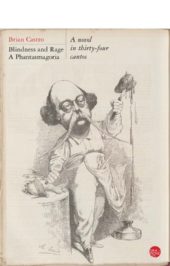

Blindness and Rage: A Phantasmagoria

Blindness and Rage: A Phantasmagoria

by Brian Castro

224pp, $26.95

ISBN 978-1-925336-22-1

Reviewed by JOSEPH CUMMINS

Brian Castro’s eleventh work of fiction is a profoundly playful novel about life, death and authorship. Faced with a terminal diagnosis, Lucien Gracq contemplates the meaning and meaninglessness of life as a town planner. Given fifty-three days to live – this is an allusion to Georges Perec’s novel 53 Days, which he left incomplete at his death – Gracq decides to focus on finishing his epic poem, Paidia. He moves to Paris and there joins an absurdly shadowy society of misfit intellectuals. Who wouldn’t be intrigued by this?

This is not an advertisement for euthanasia. We welcome those with a terminal illness who are interested in the test of time, who think hard about sacrifice and the culture of intellectual legacies. Members will, through an act of law, erase their name and bequeath their work to a living other. It is plagiarism in reverse we practice, to provide a cleansing service before oblivion. We are Le club des fugitives. (20)

A highly literate kind of gallows humour infuses Castro’s novel in perhaps the most concentrated doses of his oeuvre. Here it is harnessed to his concerns with the erasure of the self and the attempt to retain some sort of life beyond death, lenses that Castro often equips to view these universal questions. ‘What does it mean / if not pure and present vanity / to think of your memory / as a future commodity?’ (21), Gracq asks, scornful. Subtitled ‘A novel in thirty-four cantos’, this short novel is written in mostly free verse.

Using the brevity and concentration of verse, Castro thinks on life, death, the poetic body – the body that is created by poetic language – in terms of play. He is intent on wringing every last drop of poetic and philosophical potential out of this concept. We follow our poet planner Gracq as he dances with the play of death, grapples with the play of authorship, messes with the play of quotation, shimmies around the play of the imagination, and slides between play and meaning. Gracq theorises that ‘It is catachresis – the crossing over / which extends life; gives shards of signs / a shiny meaning, pure illusion, / a reality or just a game of cards’ (131). After sending drafts of his epic poem to the leader of the Fugitives, George Crepes (an anagram of Perec?), Lucien receives a playful critique:

Your Paidia is losing its serious play,

verging on frivolity. There is no crossword

or chiasmus, no game of Go.

There is no verbal Rubik’s Cube

or even rubrics cubed; no red lining,

no rules, injunctions, prescriptions.

The word I say to you is No

do not go down this tube of mining

your emotions at this late stage.

Your heart is thumping out the words;

there are so few beats left to submit. (123-4)

The beats of the heart measure both life and poetic tension and release. The examination of a poetic body – ‘your body is your life / a work in progress’ (39) – particularly the way Castro looks back and forth at poetry and the process of aging, one through the other, is perhaps the aspect of this novel that struck me as its most consistently serious statement.

Always attuned to the experience and implications of being in and out of place, one of the most entertaining aspects of Blindness and Rage is the constant and ever-more farcical shifts between the Adelaide, Paris, and a constellation of other locations, including Hong Kong and Dubbo (in western New South Wales). I particularly enjoyed the juxtaposition between Adelaide and Paris – ‘For a long time, Lucien used to go to bed early / thinking fantasy oh, fantasy! / He had become too staid – / perhaps it was living in Adelaide’ (60). This allusion to the opening line of Proust’s masterpiece is quite hilariously subverted in the next line: ‘Where is my fantasy? / He shoved a DVD of Sex and the City / into the player but it did nothing / to divert the hurly-burly’ (60). Later the comedy continues as the Australian obsession with sport is mythically mocked: Gracq ‘was from the South, / some say it is a barbarous place / whose only activity is sport; / perhaps it is like Sparta’ (162).

But aside from these amusements, the sharp relief between centre and margin also produces sincere and poignant meditations on memory. Transported to the Western Plains Zoo in Dubbo – and I thought Adelaide was a long way from Paris – we encounter the unique moments of pathos that for me marks Castro’s work.

…knowing how years hence you would be sorry how quaint all your promises were, how you knew well the passions of others and decided you were not the sort to treat them lightly, how you remembered the past incorrectly, conflating your own experience with that you had read, in wonderment, and ultimately, in forgetting. (180)

Skipping in an and out of the shining auras of works such as Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, the love letters of Kafka, and with a soundtrack of Chopin, Blindness and Rage is as virtuosic as it is opaque. Cheeky references spring up on almost every page – I noticed numerous reworkings of Proust’s famous opening line – ‘he was in search of lost emotion – / words which slowed the heart and / humoured the day and held / the night with chimeras’ (2) – but that is probably because I am most familiar with that work. Castro’s writing is nimble and at times resonant, but the relentless allusion to a wide range of writers, philosophers (and pornographers) can at times stifle ones enjoyment. Of course Castro the modernist wants us to work for it – he’s playing with expectations about meaning, difficulty and the labour (and pleasure) of reading.

While it is Castro’s first verse novel, the playfulness at the core of Blindness and Rage links it closely to much of his oeuvre. Despite his early doubts about writing and the commodification of memory – and following the hijinks of his time with the Fugitives, a love affair with his neighbour in Paris, and many half-blind alleys of mischievous reference – I feel like Gracq ends up reaching a conclusion that rings an uncannily familiar note to Castro’s masterwork Shanghai Dancing: ‘To be able to write is not to say anything / but to put small things together, / shards which once cut into memory, / made up of roots and calligraphy’ (196). While seemingly far removed from the territory covered in the ‘fictional autobiography’ Shanghai Dancing, Castro’s latest offering continues to map the space between memory, place and creativity. It may confound, but Blindness and Rage is just as rewarding.

JOSEPH CUMMINS writes about contemporary Australian literature and popular music. His first book (with Ashley Barnwell) Reckoning with the Past: Family Historiographies in Postcolonial Australian Literature, will be published in 2018.