Roberta Lowing reviews After Gilgamesh by Jenny Lewis

by Jenny Lewis

ISBN 9781907327100

Reviewed by ROBERTA LOWING

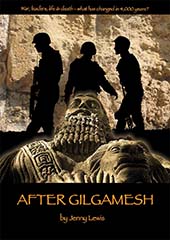

It would be easy to categorize After Gilgamesh (1) as a missed opportunity or a token memento. This 64-page paperback is a record of what is billed as the “unique contemporary music theatre production” (2) After Gilgamesh, which was performed in March 2011 by the Pegasus Youth Theatre Companies, comprising of the Pegasus Youth Theatre, Dance and Production Companies. (The paperback, here known as ‘the text’, was sold as a ‘special programme’ at that performance and can be ordered on-line, via the website www.mulfran.co.uk).

While it has little to interest a poetry purist, the UK-published text is a pointer to the possibilities of poetry in the digital age, notably in the intersection and dissemination of poetry and performance art. After Gilgamesh is definitely worth a look by the committed poet activist and/or those reader/writers who believe that poets are not only the “unacknowledged legislators of the world” (3) as per Percy Bysshe Shelley, but also George Oppen’s statement that poets are “the legislators of the unacknowledged world”. (4)

The published text’s amalgam of poetry and Iraq War subject matter also has the potential to be used as a teaching aid for high school students, in both poetry/English courses and contemporary and ancient history classes. (5)

It would be churlish to begin by commenting on the text’s omissions so let’s focus on After Gilgamesh’s strengths. The play was written by English poet Jenny Lewis who, as she notes in the text’s introduction (6), became fascinated by The Epic Of Gilgamesh, the nearly 5000-year-old story which, as Lewis summarizes, is thought to be the oldest piece of written literature in the world.

Lewis had been researching her Welsh father’s WWI Army experiences in Mesopotamia (now part of Iraq). Commissioned to write what she describes as a verse drama, Lewis collaborated with Iraqi playwright Rabab Ghazoul and theatre director Yasmin Sidhwa. The result is a four act play (with interval) which cuts between the experiences of a British soldier in Iraq after the 2003 American Army invasion, and the Ancient World setting of Uruk, 2700 BC, which follows the bloody adventures of the Uruk king/god/tyrant Gilgamesh and his best friend, the ‘wild man’ Enkidu. The journey-of-discovery structure finds the obvious parallels in the issues of conflict and humanity, best summarized by the query printed on the book’s front cover: ‘War, leaders, life & death – what has changed in 4,000 years?’

The play’s dialogue, as recorded on the page, is a mix of fictional prose, adapted news reports, free verse, rhyming couplets, slant rhymes and – arguably the dominant poetic form in the text – quatrains with an ABCB rhyme. On the page, the latter emphasizes the play’s sing-song (no pun intended) approach. This is presumably designed to appeal to younger audiences; something enhanced by the slang used throughout (“Don’t even go there”) (7); the broad humour (‘Let’s kill him off with some disease/ … Perhaps bubonic plague, I’ve got some fleas”) (8); war satire (“It was those evil Commies” “… wrong war, General”)(9); and the presence of an ‘Afro-pean’ Chorus, which spans both eras (“Count your blessings, Gilgamesh/ The simple things in life are best;/Enjoy your family, avoid stress,/This is the way to happiness./”) (10)

Interestingly, all of the above read better than you might think on the page: the slang, farce and satire add vitality. The almost vaudevillian aura evoked by the boisterous market-place Ancient World scenes – and the inclusion of black and white photos of the crew and young cast in rehearsal (11) – gives you a sense of what the play might have been like on the stage.

On the page, the poetry lover’s best rewards come from the incorporation of classic texts, such as the delicately resonant lines (lineated as below):

Who can climb the sky?

Only the gods dwell forever in sunlight.

As for man, his days are numbered,

whatever he may do, it is but wind.

The Epic of Gilgamesh

Tablet III of the Old-Babylonian version. (12)

Also evocative are the excerpts (too-brief for poetry purists) from the work of 13th century Persian poet Rumi (“Beyond right and wrong there is a field. I will meet you there.”) (13) It was an inspired decision to sample, near the end, what is movingly described in the Scene Notes as “a collage of loss” (14): The Gaza Monologues which, as the Production Notes by director Sidhwa explain, were “written by young people from Gaza of a similar age (14 to 19 years old)”. (15)

Inevitably, though, there are problems with presenting a play-as-text. The play may only span 35 pages but – even if text readers have the luxury of being able to double-check the cast list – it is still hard to keep track of the 30-plus characters who zip in and out of the often-brief scenes.

Another notable drawback for the reader is the omission of music. Writer Lewis notes that the reason why the lyrics for the songs used in the 2011 performance were not included in the text was “to give future producers a free hand in interpretation”. (16) However, her tantalizing references (17) to “a driving heavy metal piece” and “the haunting ‘Alaiki mini salem’ for the first dance sequence … (sung) in Arabic” emphasize the unfinished feel, or sense of absence, in the published text. (18)

As someone who volunteered in a not-for-profit co-operative for four years – as producer-director of an environmental television programme – I have enormous sympathy for the constraints of no-budget productions. However, limitations can lead to creative solutions. Yes, it would take money (but not a great deal) to record a performance of After Gilgamesh and include it with the published text, either as audio only (on CD or digital file) or audio-and-visual (DVD/digital file). (19)

No visual or audio excerpts appear to be currently available on the publisher’s or the writer’s websites although clips of the play may be elsewhere on the internet.

However, watching only on computer could affect both potential audience numbers and the visual quality of the production. That would be a shame because After Gilgamesh is a text that hints at the possibilities for poetry performed and distributed in the 21st century.

NOTES

1. After Gilgamesh by Jenny Lewis (Mulfran Press: Cardiff, 2011).

2. ibid, p.13.

3 & 4. Why Poetry Matters by Jay Parini (Yale University Press: New Haven, 2008), p.1. This is an effortlessly readable and intelligent summary of the key issues affecting modern poetry, from the influences of past masters to a discussion of traditional forms and poetry’s political engagement in the modern world. Thoroughly recommended.

5. It would be nice to see After Gilgamesh use its play script as a starting point for deeper discussion. A more ambitious idea would be to imitate books such as Duras By Duras (City Lights Books: San Francisco, 1987): a journal of essays and comments by The Lover novelist and the Hiroshima, Mon Amour scriptwriter Marguerite Duras, and other French writers and intellectuals, on Duras’ script for the 1974 film India Song. This posits the film’s shooting script (a copy of which is included in the text) at the centre of a discussion about inspiration, films, language-as-politics and Duras’ career.

6. After Gilgamesh by Jenny Lewis (Mulfran Press: Cardiff, 2011), p.9.

7. ibid, p.32.

8. ibid, pp.41-42.

9. ibid, p.59.

10. ibid, p.63.

11. ibid, pp.16-25.

12. ibid, p.27.

13. ibid, p.29.

14. ibid, p.60.

15. ibid, p.12.

16. ibid, p.10.

17. ibid, p.9.

18. Anyone who saw George Gittoes’ engaging 2005 documentary Soundtrack To War, which explored the music being played by both locals and foreigners in Baghdad during the American occupation, will appreciate the irony that an occupied city often becomes a crossroads of civilizations. The variety of music being performed by the inhabitants in the film – whether it is singing gospel (the Americans) or playing heavy rock (the Iraqis) – is an often poignant reflection of the stresses experienced by those inhabitants.

19. The crucial component here is sound: humans will happily watch low resolution images if the audio is acceptable but they will quickly switch off if they cannot hear clearly. Frankly, though, in these days of digital recording there is no excuse for not being able to produce – at low cost – a plainly framed but audible record of the production.

ROBERTA LOWING‘s poetry has appeared in journals such as Meanjin, Overland and The Best Australian Poems 2010. Her first novel Notorious was shortlisted for the 2011 Prime Minister’s Literary Awards and the Commonwealth Book Awards. Her first collection of poetry, Ruin, about the Iraq War, was co-winner of the 2011 Asher Literary Award.