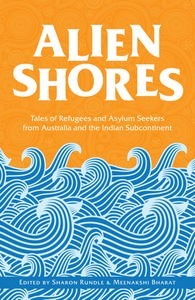

Sunil Badami reviews Alien Shores Ed Sharon Rundle & Meenakshi Bharat

Ed. Sharon Rundle, Meenakshi Bharat

Brass Monkey Press

ISBN 9780980863932

219 pages, RRP $24.95

Reviewed by SUNIL BADAMI

Exile is a powerful undercurrent in the Indian imagination. One of its defining myths, the Ramayana, tells the story of a noble prince banished from his home and spending much of his exile rescuing his wife from the clutches of the tyrannical ruler of the island of Lanka.

Despite Rama crossing a still extant land bridge to reach her – and the Ramayana spreading throughout South East Asia – Hindus were forbidden from crossing the kala pani, or black water, for fear of losing their caste. It was only starvation and desperation caused by the imposition of imperial cash crops such as cotton, jute and opium that forced many to become indentured coolies in far-flung plantations in South America, the Caribbean, Africa, South East Asia and the South Pacific, making Indians one of the world’s most widespread diasporas.

Exile and alienation also figure deeply in Australian mythology, the ‘tyranny of distance’ weighing heavily, our backs turned from the alien, hostile landscape of Frederick McCubbin’s lost white children and picnics at Hanging Rock to the sea, over the sea, overseas, to ‘old England, the beautiful’ and more recently, ‘the land of the free.’

Our alienation from our own ‘terra nullius’ have created a history full of, as Mark Twain quipped, ‘the most beautiful of lies.’ As the narrator of Michelle Cahill’s ‘A Wall of Water’ observes, ‘The past is a territory. So much of it has been excised.’ (68)

Both Australia and India – at once cradles of civilisation and new, multicultural nations – were founded not so much on inclusion as exclusion. India was born out of the trauma of Partition. The Federal Australian Parliament’s first Act was the White Australia Policy. And both countries have, by way of so-called ‘post-colonial literature,’ explored both the agony of exile and the mythology of history.

As the critic Pierre Ryckmans observed in his essay, Lies that Tell the Truth (quoting C. S. Lewis): ‘Myth is the oldest and richest form of fiction. It performs an essential function: “what myth communicates is not truth but reality; truth is always about something—reality is what truth is about.”’[i]

As Ryckmans points out, ‘truth is grasped by an imaginative leap.’ What makes us human isn’t language – animals, from bees to whales, can communicate; apes can be taught to sign. What makes us human is our imagination: to see and believe that which is not seen. When imagination succeeds, it can reveal the truth. Yet myth often arises when memory fails.

Myths abound about refugees and asylum seekers: they’re opportunists, economic migrants, queue jumpers, potential terrorists, they want to change the country, throw their children overboard, carry contagious diseases.

As Ross Gittens observed, the fear those myths engender is ‘so deeply ingrained, so visceral, that it’s not susceptible to rational argument. It would be nice if a greater effort by the media to expose the many myths surrounding attitudes towards asylum seekers could dispel the fear and resentment, but it would make little difference,’[ii] especially when neither side of politics cannot imagine any other ‘solution’ than the Pacific one, and facts and faces are lost amidst the lies, damn lies and statistics.

It seems ironic, then, to combat such rampant dishonesty and fearful mythology with fiction. But as Rosie Scott notes in her excellent foreword to this collection of ‘Tales of Refugees and Asylum Seekers from Australia and the Indian Subcontinent’:

It is the writer’s act of imagination which is the basis of all good fiction, the kind of fiction that opens new worlds

to the reader.

(3)

Asylum seekers and refugees have impacted on the popular imagination as much as they have the political debate, with the decade since the Tampa producing books and films such as Eva Sallis’s Commonwealth Writers’ Prize-shortlisted The Marsh Birds, Michael James Rowland’s moving film Lucky Miles, John Doyle’s acclaimed Marking Time, Nam Le’s award-winning short story collection The Boat, Anh Do’s best-selling Australian Book of the Year, The Happiest Refugee, and SBS’s successful Go Back to Where You Came From.

In all of these, refugees were not just presented as faceless statistics, but as real people with moving stories: even those opposed to ‘queue jumpers’ and ‘illegals’ and instrumental in formulating the Pacific Solution, such as Peter Reith, could not help but be moved when faced with real people and their often heart-breaking stories.

One hopes, too, that the stories found in Alien Shores will do the same. Many of its stories are devastating – not only for the horrific and tragic events that precipitated flight – but for the sorrow, regret and guilt that remain once immediate fear has receded: the father forced to leave his six year old daughter behind in Abdul Karim Hekmat’s sweet and sad Life Hanging in the Balance; the social worker who must live with her refusal to help in Amitav Ghosh’s eviscerating Morichjãpi; the little girl who cannot help ‘the kind man, someone else’s father from a strange land, being taken away’ in Anu Kumar’s delicate and haunting Big Fish.

Much less the guilt of the well-meaning ‘middle-class do-gooder’ like me, who, for all their ‘sense of shame at the cruel and opportunistic Liberal government’s inhumane treatment of refugees’ knows no amount of ‘waving placards’ – much less cc’ing internet petitions – will ever do much for ‘those desperate, innocent people locked up indefinitely in disgusting concentration camps in the middle of the desert.’ (Page reference)

Over the course of an entire book, this guilt could lead to the very thing Alien Shores must be seeking to avoid, if not change: compassion fatigue. As Go Back to Where You Came From showed, there is as much a limit to imagination as there is to compassion, watching those unsympathetic to refugees relating to them on a human or personal level, but continuing to justify their opposition to more humane treatment.

As the narrator of Linda Jaivin’s tender and hopeful Karim says, ‘I haven’t been able to cope with other people’s misery. It’s like I’m full up, there’s not room for one drop more. It’s also like I’ve become porous: it’s as if I let down my defences and opened myself up even a bit, all the sorrow in the world would come flowing in. I got good at fortifying my boundaries.’

I wondered—just as I did watching Go Back to Where You Came From—what reading Alien Shores will do to change closed minds and move hard hearts, when it’s unlikely the people who really need to read this book will? After all, although Go Back to Where You Came From’s viewing figures were the highest in SBS history, the X Factor had double the audience on the same nights.

And that indifference and resistance is as exacerbated by depictions of refugees as pitifully passive tragic victims as the demonization of them by right wing politicians and shock jocks. One wonders if Anh Do’s success is because the ‘happiest refugee’ leavens his suffering with hope and gratitude, as much as infusing his story with greater agency than flight.

Indeed, where Alien Shores especially succeeds is in offering, through often rich, evocative and sometimes visceral writing—as in Deepa Agarwal’s gripping The Path (which at first could describe any flight from danger, only small but telling details revealing that refugees have existed as long as war has), or Joginder Paul’s horrifying Dera Baba Nanak—not just new perspectives beyond those stereotypes, but within us.

Many stories from both countries feature middle-class protagonists or narrators, which work effectively at shaking the very middle class complacency many of us are guilty of, including Sujata Sankrati’s involving and moving No Name, No Address, Meenakshi Bharat’s The Lost Kingdom, Tabish Khair’s A State of Niceness, and especially Ali Alizadeh’s confronting and shattering The Ogre.

In this regard, the collection’s stand out story is co-editor Sharon Rundle’s excellent Ariel’s Song, which makes refugees of ordinary Australians, giving them the same hopelessness and impossible choices. The story offers, in the way only good fiction can, the imaginative empathy that comes with connection and compassion: of putting ourselves in someone else’s shoes and feeling what it must really be like for them, especially when the ‘they’ are us.

The queue grows longer every morning. By the time our water container is filled I’ve at least sweated away half that much fluid. Somewhere down the line Bill repeats the same story he tells every day: I had a ute and a boat and a business—a big house—all gone—gone—all gone. (107)

The subtitle suggests a thematic connection between Australia and India, featuring subcontinental asylum seekers from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Burma. Unfortunately this makes the very good stories from China, Indochina and East Timor seem incongruous, and made me wonder: what about African refugee stories, such as Majok Tulba’s? Or South American? Or Balkan?

Still, what they do reveal is the way the lines between one region and another are continually blurred, the way countries are connected by tides of movement in a globalised age in which multinational corporations and transnational terrorists have rendered borders obsolete as much as hybridised identities like mine have dissolved national ones – a point made violently in Jamil Ahmad’s The Sins of the Mother, in which nomads are caught between ancient traditions and modern laws, ‘the lines of demarcation… confusing to all.’ Much like the increasingly bleeding boundaries between personal and political, truth and fiction, history and myth.

The waves of suffering crashing upon our shores, the tide of sorrow set adrift on excised territories, the razor wire rolled out around ‘unAustralians’ are disheartening, but for all the noise of political ‘debate’ and media commentary, the power of literature, as Scott points out, ‘to move people [and] allow us to see into one another’s hearts, to foster compassion and understanding and inspire political action works in a way that almost nothing else does,’ remains long after everything else has been washed away.