May 19, 2012 / mascara / 0 Comments

Dark Night Walking With McCahon

Dark Night Walking With McCahon

by Martin Edmond

Auckland University Press

Reviewed by MICHELLE DICINOSKI

On April 11, 1984, the major New Zealand artist Colin McCahon disappeared unaccountably in the Sydney Botanic Gardens. McCahon and his wife Anne were visiting Sydney as guests of the Sydney Biennale when McCahon, then aged 64, disappeared during a walk through the gardens. He was found five or six kilometres away, disoriented and suffering memory loss, in a routine patrol of Centennial Park in the early hours of April 12. He carried no identification with him, and could not say who he was. When he was taken to hospital, he was diagnosed as suffering cerebral atrophy, probably the result of his long-term alcoholism.

What happened to McCahon during those lost hours? Where did he go, whom might he have met along the way, and what did he see on this “dark night”? These are the questions that provoked Martin Edmond to write Dark Night: Walking With McCahon, a creative non-fiction account of Edmond’s attempt to imagine, through walking the same part of Sydney, McCahon’s lost hours. Edmond explains:

I thought and thought about it, and at some point conceived the idea of replicating that lost journey—not in search of authenticity, nor documentary truth, nor even simple verisimilitude, since all of these were by definition impossible. Rather I wondered if I could arbitrarily choose a route and along it find equivalents for the fourteen Stations of the Cross?

(21)

The Stations of the Cross is a representation, in fourteen parts or ‘stations,’ of Christ’s last hours, beginning with his being condemned to death, and concluding with his death and entombment. In churches, visual depictions of the Stations of the Cross become stations through which worshippers pass on a circuit of devotion. Edmond’s decision to try to encounter McCahon and map equivalents for the Stations of the Cross through this ‘arbitrary’ route is not itself an arbitrary choice: McCahon’s work engaged with matters of faith, though he himself was not religious—“not anything”, as he strikingly put it.

Dark Night is structured in four parts. The first, “Testimony,” describes how Edmond’s life has briefly connected with McCahon’s in a few instances. Most importantly, Edmond spent his childhood in a bedroom in which a McCahon painting hung on the wall. The painting fascinated Edmond even as a small child; his curiosity with the artist and his art has been lifelong. The second, and longest, section, “Psychogeography,” describes Edmond’s journey through what might have the route that McCahon took in his lost hours, a route which is structured around the Stations of the Cross and ends in Centennial Park. The third section, “Dark Night,” describes a night spent in Centennial Park itself, and the fourth, “Beatitude,” takes Edmond back to New Zealand in a kind of coda.

As perhaps may be evident from this structure, Dark Night is ambitious, but it also meanders, in the sense that it is willing to follow and linger along the routes of a curious mind, however non-linear those routes may be. Initially, it seems that Edmond is setting out in pursuit of something, though what it may be is unclear. What the book becomes, however, is something else. Edmond produces a kind of meticulous account of a small stretch of a city, a detailed and sharply observed portrait of Sydney a decade into the 21st century. It is a city of convenience stores and pubs, of homeless men sleeping in doorways, “each with his hands tucked between his thighs the way little children sometimes sleep,” of midnight parks in which the author claims to see the trees breathing.

As he walks, Edmond also muses on a remarkable range of topics: his own father’s alcoholism, methods of crucifixion, how Torahs are constructed, the sex trade at the Wall, the development of Christian Science. When we roam with Edmond, we roam not only across the physical spaces of Sydney, but also more extensively through Edmond’s mind and the connections that he makes across time and space, between an older and a newer Sydney, and between his own life and McCahon’s, between the city and its people. He wonders about meaning, and connection, and creativity, and about faith and its absence, and how they affect lives generally, and McCahon’s life and work in particular.

The structure of the book is shaped by its author’s range of interests, by his musings, and also, inevitably, by the impossibility of resolving his questions about McCahon. As Edmond himself remarks, quoting from a Pasternak poem: “To live a life is not to cross a field.” Edmond has worked as a cab driver, and his range of knowledge and his way of telling stories—picking up here and dropping off there—in some ways reflects the episodic nature of that work. But this is a book that is walking paced, and seen from the footpath rather than the street. Edmond is a flâneur, a stroller of the city, a walker who seeks to know the mind of another man by walking, and by spending a long night on a park bench.

One of the book’s greatest achievements is its depiction of Sydney now, in a now that has inevitably already passed. Edmond records highly specific details: how much change he has ($27.75) after paying his train fare ($3.80) to the city, the schooner he buys (Reschs, $5) at a pub (The East Sydney Hotel), and the discussion about the tenth Doctor Who, David Tennant, that takes place as he orders, the prints on the pub’s walls (Magritte, van Gogh, Cartier-Bresson). He describes churches, homeless shelters, excavation work, convict graffiti, contemporary graffiti, prostitutes, taxi drivers, revellers emerging from a gay club at dawn. His depiction of himself can be just as precise: he carries with him on one of his journeys “a thermos of black coffee laced with St Agnes brandy; a ham, cheese, and tomato sandwich; a banana; a tin or Café Cremes, ten small cigars of the vanilla-flavoured variety called Oriental”—along with warmer clothing and two different translations of St John of the Cross’s poem “Dark Night of the Soul.”

Dark Night is a serious book with extensive research behind it, as can be expected of a work that is, at least in part, a biography. Edmond has written across a range of genres, including screenplays and poetry, and his exacting care for language is quite delightful. His descriptions of places are particularly striking, as when he writes of visiting a friend in an art deco building, Mont Clair, on Liverpool Street in Darlinghurst in the 1990s:

the air inside Mont Clair was cool and smelled strange, like embalming fluid or formaldehyde; a wan yellow light fell across the dark varnished wood from deco lamps high up on the walls and the vacant concierge’s booth always felt inhabited by some phantom interlocutor. The lift clanked and sighed in protest as it hauled me upwards and my reflection in the mirrors with which it was lined always looked vaguely corrupt if not actually demonic. The other residents in the building were rarely seen and, when spotted, seemed pale and affrighted …

(75-76)

And so Edmond takes us there, through Sydney past and present, and all its ghosts, in search of another kind of ghost. It is what we can see—a remarkable city, a fascinated and fascinating writer—that makes the lasting impression. McCahon, the brilliant artist, is a fugitive here, as perhaps he was in life. But what Edmond finds in his pursuit makes for a memorable portrait of a city and a man —not the man who came to Sydney in 1984 and was lost, but the man who came a quarter of a century later and tried to understand.

MICHELLE DICINOSKI’s memoir Ghost Wife will be published by Black Inc. in 2013. Her poetry collection Electricity for Beginners was highly commended in the Anne Elder Award 2011, and she was awarded a Marten Bequest Travelling Scholarship (Poetry) in 2012-2013. She lives in Brisbane.

May 19, 2012 / mascara / 0 Comments

A music teacher currently calling Bondi home, Jessie Tu was born to Taiwanese mother and Chinese father. At the age of five, she immigrated to Australia- Melbourne, and then relocating to Sydney. She studied music at university having played the violin from the age of nine. She now teaches full time at the Rose Bay independent girls school Kambala and enjoys writing as a means of connecting with her community. Her poetry deals with her identity growing up as an immigrant and the comic trails and tribulations of being a ‘banana’ (white on the inside, yellow on the outside) and the shift from childhood to adulthood. She has recently received a 6 month residency as a Café Poet (a program funded by the government assisted Australian Poetry Organization) at her favourite café in Sydney – WellCo Café in Glebe. She has had her writing published in Peril Magazine and VibeWire. In December 2011, she participated in a National Young Playwrights’ Studio workshop where a selected few young Australians from across the nation came together with industry leaders to write, learn and create new works.

A music teacher currently calling Bondi home, Jessie Tu was born to Taiwanese mother and Chinese father. At the age of five, she immigrated to Australia- Melbourne, and then relocating to Sydney. She studied music at university having played the violin from the age of nine. She now teaches full time at the Rose Bay independent girls school Kambala and enjoys writing as a means of connecting with her community. Her poetry deals with her identity growing up as an immigrant and the comic trails and tribulations of being a ‘banana’ (white on the inside, yellow on the outside) and the shift from childhood to adulthood. She has recently received a 6 month residency as a Café Poet (a program funded by the government assisted Australian Poetry Organization) at her favourite café in Sydney – WellCo Café in Glebe. She has had her writing published in Peril Magazine and VibeWire. In December 2011, she participated in a National Young Playwrights’ Studio workshop where a selected few young Australians from across the nation came together with industry leaders to write, learn and create new works.

My mother’s heart is a small, good thing

My mother’s heart is a small, good thing.

It is lovely and unassuming like my stain glassed mosaic lamp

illuminating a room as an angel lights the sky.

It is calm like the winds on a gentle Sunday at 3.

It hums quietly to itself when no one is listening.

It never stirs at the absence of peace.

My mother’s heart is a small, good thing.

It sings at the sight of a neighbour’s garden

transforms her willowy features to delicate soft expressions.

Her heart is a keen student.

It swallows with the force of a sea cave, it

kills all light

Her horrendous freedom, uncaged-

Her fear is mightier than might

She hums to her own tuneful language,

Her solid stare, unpardonable-

She leaks through me like a bleeding creature

Her agility fails tonight,

And I have nothing but my intermediate embrace

To comfort and progress.

House

These walls tremor with their private language-

carves a sound sculpture of a musical elegy,

a requiem for my sleepless soul.

Unafraid,

I bring myself to this curtailing ostinato,

breathes soaked as self-pitying woe.

The city abode confines me with

a strange solitude, yearning to disperse.

Feet crawl on broken pavements

obedient in structure and anatomy –

they pace with diligent trust in my heavy head, though-

they should beware

this head is too fruitful

for small talk

and

hollow prayers.

They settle with a blur,

accepting the inevitable-

tomorrow will rise like today,

a repetition of yesterday.

May 19, 2012 / mascara / 0 Comments

Mona Zahra Attamimi is an Indonesian-Arab. She lived as a child in Jakarta, Washington DC and Manila. She moved to Sydney at age ten with her family. She has studied Anthropology and Women’s Studies at ANU and ISS in Holland. Currently she is completing a Masters in Creative Writing at the University of Sydney. She enjoys writing poetry and short stories. And through writing and reading, she is interested in exploring diverse experiences of cultural displacement and marginalisation. Her poems have appeared in Southerly and forthcoming in Meanjin. She is an editorial assistant for Mascara Literary Review

Mona Zahra Attamimi is an Indonesian-Arab. She lived as a child in Jakarta, Washington DC and Manila. She moved to Sydney at age ten with her family. She has studied Anthropology and Women’s Studies at ANU and ISS in Holland. Currently she is completing a Masters in Creative Writing at the University of Sydney. She enjoys writing poetry and short stories. And through writing and reading, she is interested in exploring diverse experiences of cultural displacement and marginalisation. Her poems have appeared in Southerly and forthcoming in Meanjin. She is an editorial assistant for Mascara Literary Review

Drifter

In my hard boots

I wandered into a field of thistles

crushing violet weeds,

bits of bricks and tiles,

broken glass from a house

I once knew. My mouth was wild,

foaming her name. I heard my child’s

moonless moaning and my house

bursting into a cake of flames.

After the rain, by the river-death,

I slept for a night in the shadow

of a broken boat. I piled humus

under my head and dreamt

of a throat

tangled in weed,

white as bone, my wife’s

goosefleshed thighs floating

in the swamp that sank

our river-home.

As I fold and unfold

a sleeping bag

by an alley and a railway track,

I brush away

the phantom of a man

drinking coffee and breaking bread

inside his daughter’s home.

Now, my hard boots hide

crooked toes,

crack bush burrows,

barks, twigs and lie

about the state of my soles.

Mangosteen

Do not say a prayer, shed a tear,

nor place a wreath on my grave,

but bury me instead under a mangosteen

tree once I’m stiff like lead.

Once I’m dead, drip mangosteen milk,

and wring the sweet white arils

till its juices soak

my funeral shroud. And when I die,

embalm my head and tuck

my teeth in black-purple rind,

let the mangosteen roots coffin

my bones, skin and spine.

When night comes, let me rustle the leaves

with my ghostly arms, and let me

scare the thieving monkey that climbs

on its fruit-bearing branch.

Once I’m freshly dead and buried under

the fallen fruits, let the soil and grass

pickle my heart and liver

in mangosteen’s heavenly pus.

May 19, 2012 / mascara / 0 Comments

Indran Amirthanayagam directs the Regional Office of Environment, Science, Technology and Health for South America, based in the United States Embassy, Lima. A member of the United States Foreign Service, he has served as Public Affairs Officer in Vancouver, Canada, Monterrey, Mexico, and in Chennai, India. He is a poet, essayist and blogger in English, Spanish, French and Portuguese (http://indranamirthanayagam.blogspot.com). He has published six collections of poetry, including The Elephants of Reckoning ((Hanging Loose Press, NY, 1993) which won the 1994 Paterson in the United States, and The Splintered Face: Tsunami Poems (Hanging Loose Press, NY, 2008). A new collection of poems in Spanish, Sol Camuflado (Camouflaged Sun) has just been published in Peru ( Lustra Editores, Lima, May 2011).

Indran Amirthanayagam directs the Regional Office of Environment, Science, Technology and Health for South America, based in the United States Embassy, Lima. A member of the United States Foreign Service, he has served as Public Affairs Officer in Vancouver, Canada, Monterrey, Mexico, and in Chennai, India. He is a poet, essayist and blogger in English, Spanish, French and Portuguese (http://indranamirthanayagam.blogspot.com). He has published six collections of poetry, including The Elephants of Reckoning ((Hanging Loose Press, NY, 1993) which won the 1994 Paterson in the United States, and The Splintered Face: Tsunami Poems (Hanging Loose Press, NY, 2008). A new collection of poems in Spanish, Sol Camuflado (Camouflaged Sun) has just been published in Peru ( Lustra Editores, Lima, May 2011).

Off the Field

In the end we have only ourselves to pick up from the grass,

the bed, the gymnasium floor. The dead will have their say

in dreams, and fond ones too, how the boy used to laugh

when chasing the ball on Duplication Road, or the girl back

in the village, shyly accept the glance of her neighbor’s son,

by the well, over a garden wall, the victims, the left behind

after the tsunami or the shelling without end, abroad,

processed, rebuilding their lives in the company of

Australians or Canadians, new people, while the distant war

on its nightly visit to parents, single or a pair, does not curse

the kid born away, who loves the latest fad on satellite radio

and the girl in his class who sports an infectious laugh.

Sharing the Load

There are friends who travel part of the way, then drop off

into the woods, I miss them in the darkness and thank them

here for their time–the one who sliced the last stanza off

a poem which later became another man’s favorite to speak

in the ear of love and feel its breath whistle by the lobe,

to eat and be eaten, write as Cyrano de Bergerac, thank you

for giving me the chance to serve. And the other who said

I have a secret country in my verses, that lends color

and light to my images, Alastair, let me write your name

although you said you cannot carry books any more,

that the local library must do. I understood. I have

moved a library through the Americas and the books

are dusty, creased and tired and many still unread,

time to house them with good air flow and a bookkeeper,

somebody else, a young man or woman, my own children,

if they wish to carry the load. There is gold in the paper

and lead, memories of a far-away life, with elephants

crossing at dusk, white ants hungry for pages.

May 17, 2012 / mascara / 0 Comments

Susan Hawthorne is the author of six collections of poetry, the latest of which is Cow (2011). Cow was written during a 2009 Asialink Literature Residency based at the University of Madras and funded by the Australia Council and Arts Queensland. Her previous book, Earth’s Breath (2009) was shortlisted for the 2010 Judith Wright Poetry Prize. A chapbook of poems about war, Valence, will be published in late 2011. She is Adjunct Professor in the Writing Program at James Cook University, Townsville. She has been studying Sanskrit at La Trobe University and ANU for five years.

Kālidāsa’s Meghadūta

Kālidāsa’s Meghadūta (Cloud Messenger) from approximately the 4th century CE is a poem of 111 stanzas. This poem is based on reading the first 20 stanzas of the poem in Sanskrit. Meghadūta is one of several lyric poems by Kālidāsa who wrote three plays as well as epic poems. He is one of the most important poets writing in Classical Sanskrit. Translating for Sanskrit provides many challenges, and in this version I take poetic licence in order to make the poem work in English. The Sanskrit metre in which it is written is mandākrānta, a slow elegiac metre.

Twenty stanzas of Meghadūta

a whole year passed and the Yakṣa pined

though he lived in pleasant surrounds

among Rāmagiri’s shady trees

and the holy waters of Sītā

yet still he ached

only himself to blame for Kubera’s curse

his mind bent by longing for her

love bangle slipped from his famished arm

with bittersweet pangs of love

he hungered on that lonely mountain top

on a windy day portending monsoon

he saw an elephant cloud rutting the cliff face

his yearning peaked as he stood

before this phantasm of elephant

dry-eyed tears welling inside

even the cheerful mind is ruffled

by the sight of a rough-skinned cloud

he wished his arms a necklace

as the month of Śrāvaṇa approached

the month of listening he prepared

to send news through the cloud ear

he made an offering of fresh kuṭaja flowers

spoke aloud his words filled with love

sustenance for his beloved

his mind bent by yearning

he clutches at cloud elements

vapour light water wind

mistakes cloud breath for vital breath

poor lovelorn Yakṣa can’t sense

the mirror from its reflection

Yakṣa speaks to the cloud saying

I know you are born into the world-wandering

shapeshifting clan related to thunder-bearing

Indra I call on you to help me most lofty one

my kin are far away and destiny tells me

to make a humble request though it be futile

rain-giver you are a refuge in sticky heat

Kubera has parted me from my beloved

and I beg that you travel to her in Alakā

with my message where you’ll find a palace

bathed in the light of a crescent moon on the head

of Śiva standing in the outer garden

ascend the path of the wind sky-fly

so the wives need no longer sigh

at their unravelled hair imploring

their well-travelled husbands to return

whereas I in thrall to Kubera

have neglected my beloved

without obstruction follow the jet stream

how you float unlike my beloved

her heart like a wilted flower

she needs the thread of hope

to buoy up her spirits in fruitless

counting of days and nights

as the wind drives you slowly slowly

the cātaka bird sings sweetly sweetly

skeins of cranes are in flight

cloud seeded they fly in formation

like a garland aloft pleasing to

the sky-turned eye

your sky companions the gander kings

have heard your thundering gait

they long for Lake Mānasa so high

they watch for mushrooming earth

and carry food strips of lotus root

as you fly together to Mount Kailāsa

lofty mountain embraced by cloud

rain tears and farewells marked

by Rāmagiri’s receding footprints

steaming tears stream down

the mountain’s face a knot

of loss born of long separation

oh cloud listen to me

let your ears be drunk

on sound listen follow

the path laid down

drink from bubbling streams

rest when exhausted

beneath you bewildered

women watch the crowd

of elephant clouds a shiver

of north wind carries off

the mountain tusk

beware the quarter elephants

face-to-face a sliver of Indra’s

bow rises from the anthill

a kaleidoscope of colours

in crystalline refraction

your indigo body glittering

like a glamour of peacocks

fruits of harvest grown

on moisture from you

fertile as the wombs

of women sweet sacred

smell of turned earth

climb the brow to the cloud-road

ride the spine of Āmrakūṭa

the ground awash with

your downpour extinguishing

wildfire such kindness is

returned providing refuge

for high flying friends

cloud braid lies along Āmrakūṭa’s

spine fringed with mango orbs

the mountain a curve of breast

its dark nipple in the middle

a coupling of gods looks

at the pale vastness of earth

the young wives of forest nomads

frolic in thick mountain arbours

you sprint the rim of mountain

streams riven by strewn boulders

like the cross-hatched pattern

decorating the body of an elephant

you whose rain is shed drink

the must-infused water of wild

elephants water-clumped

jambū trees obstruct your way

the wind cannot lift a solid mass

a void is light fullness is gravity

May 17, 2012 / mascara / 0 Comments

Kenneth Steven’s tenth collection of poems is appearing in the summer of 2012. He’s from Highland Scotland and much of his work is inspired by the wildscape of the north and west of the country. He’s also a widely published writer of prose for adults and youngsters alike, and he translates the work of many Norwegian authors.

Kenneth Steven’s tenth collection of poems is appearing in the summer of 2012. He’s from Highland Scotland and much of his work is inspired by the wildscape of the north and west of the country. He’s also a widely published writer of prose for adults and youngsters alike, and he translates the work of many Norwegian authors.

www.kennethsteven.co.uk

A Green Woodpecker

The day is like dead wood –

No colours, only shades of grey,

The gentle breath of my steps

Leaves a ghost story written in the grass.

A stillness like that when snow falls

Except there is no snow, and none all winter –

Only the river in its silvering among the trees

Whispers the same old journey to the sea;

Only the moon, low above the hills,

Frail as a ball of cobwebs.

On moss feet, I go into the wood

And a great door closes behind me:

Little quiverings of things

Quick among twigs;

Two deer, their eyes listening,

Flow into nowhere in a single blink.

I look up, into a pool of light

And hold my breath:

Swans stretching north

Swimming the open sky –

The silence so huge

I hear their wings.

And I think,

As I begin to go back home;

I came here searching one bird

And found all this instead:

How like my life.

Otter

light swivels on the night edge:

the full moon’s eerie beam

wobbles like a child’s balloon, huge, and breaks

upwards at last, into the clearing dark

otter trundles over wetscapes, crying

as points of milk-white stars shine clear;

he curls into himself in seaweed

through the swell and ebb of tide until

the oystercatchers drip their calls across the sky

and orange gold the dark melts into day –

then he’s off, a scamper on the sea edge

scenting, searching, circling –

flowing into river edges, a thousand streams

sewn inside the silk of him, for ever

May 17, 2012 / mascara / 0 Comments

Gillian Telford is a NSW poet who lives on the CentralCoast. Her poems have been published regularly in journals including Blue Dog, Five Bells, & Island & her first collection Moments of Perfect Poise was published (Ginninderra) in 2008. Longer poem sequences have twice been shortlisted for the Newcastle Poetry Prize & published in anthologies The Honey Fills the Cone (2006) & The Night Road (2009). In 2010 she worked in collaboration with choreographer Francoise Angenieux & composer Solange Kershaw on Poetica: Five Arrivals which featured as a regional event in the Sydney Writers Festival.

Gillian Telford is a NSW poet who lives on the CentralCoast. Her poems have been published regularly in journals including Blue Dog, Five Bells, & Island & her first collection Moments of Perfect Poise was published (Ginninderra) in 2008. Longer poem sequences have twice been shortlisted for the Newcastle Poetry Prize & published in anthologies The Honey Fills the Cone (2006) & The Night Road (2009). In 2010 she worked in collaboration with choreographer Francoise Angenieux & composer Solange Kershaw on Poetica: Five Arrivals which featured as a regional event in the Sydney Writers Festival.

displacement

(i)

From the incoming tide

I rescue a stone—

deep olive green

tinged with yellow buff.

Its colours bring echoes

of old growth forest, as though lifted

from leaf-litter, moss and fungi

but stranded here

among the pastel shells,

the bleached and silvered grit,

it’s a misfit

dumped on a tidal surge.

I roll it in my palm, turn

and stroke it with my thumb,

rub away each grain of sand

and hold it till it warms.

(ii)

In waves of harassment, the hostile

natives dive and shriek—

From the fig’s leafy head,

crouched in defiance— a red-eyed

intruder, huge and pale, keeps

them at bay with great snaps

of its bill and raucous cries.

When we’re talking of birds

it’s a summer migrant with many names—

stormbird or fig-hawk, rainbird or hornbill;

a channel-billed cuckoo, flown south

to breed and find hosts for its eggs.

As I watch it struggle against the flock,

I think of its journey

across the ocean, grey wings beating,

hour upon hour—

driven by instinct and drawn

to our plenty,

each year they find nurture

despite the clamour.

(iii)

Across theTimor Sea, the boats

keep coming.

Some we hear about, some we don’t—

Some will wait quietly, others won’t.

the third bridge

for my mother

It was a clean, sharp day

cut through with winds

from the Southern Ocean, so we wrapped

her in rugs and pushed the wheelchair

along the boardwalk, through rushes

and reedbeds, the grieving swans

the calling, circling terns.

At the third bridge, we stopped.

Beneath us, a tidal high,

the wind-dragged, surging estuary,

its sun-flecked surface.

And there we took turns to toss

him over— handful by handful,

back to the river, back to the ocean.

But caught at first

on gusts of wind, his ashes

lifted against the light

then circled and swirled in exultant loops

before the final fall—

the quiet passage beneath the bridge.

May 17, 2012 / mascara / 0 Comments

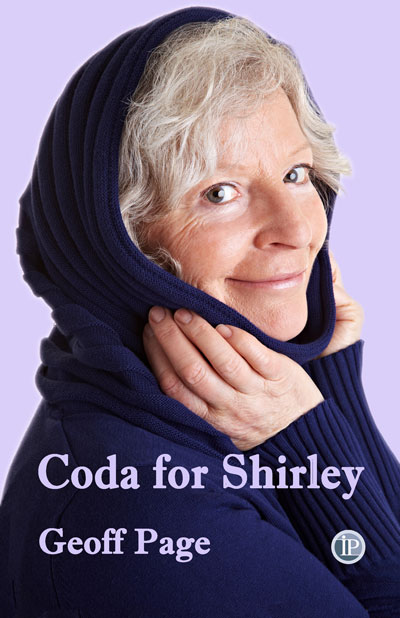

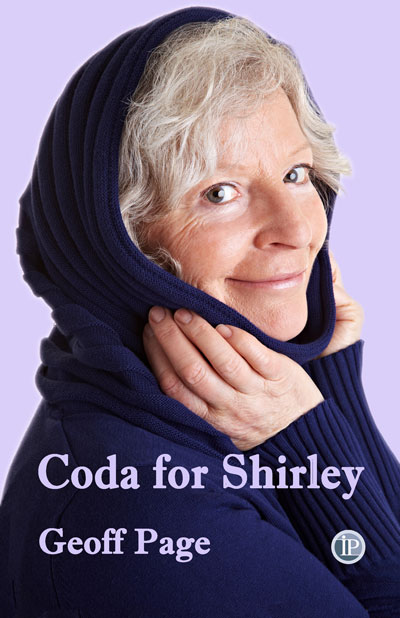

Coda For Shirley

Coda For Shirley

by Geoff Page

Interactive Press

ISBN 9781921869303

Reviewed by LYN HATHERLY

What a shame that light verse is currently not the most popular genre. For Geoff Page’s new book Coda for Shirley is playful, intriguing and beautifully constructed. This verse novel makes you wish that other poets might ‘Bring Back Scansion! Bring Back Rhyme’ as it does its best to persuade readers and other poets to share Geoff Page’s love of formed verse and the music that accompanies it. Geoff himself it seems has much in common with the gentle and ironic tutor who taught Shirley:

to master my tetrameters,

avoiding, with more stringent pen,

the doggerel of amateurs. (p.8)

Since these verses never lapse into doggerel, or waste words, they are both stringent and nicely astringent. Perhaps Geoff Page, like Whitman has found:

that free verse wafted off a little;

rhyme stayed closer to the ground. (p.5)

This verse novel follows on from Geoff Page’s 2006 verse novel, Lawrie & Shirley: The Final Cadenza, and like that book it’s amusing to listen to as well as to read. It must have taken Geoff some time to get the metre and rhymes right, and I’m sure there were times he was tempted to give up the struggle. Finally, I think the effort is well worth it since these satirical tetrameters managed to fix themselves in my mind as mnemonics and stay there echoing through my dreams and days, entertaining me long after I’d put the book down. Geoff Page might be modest but this book is an immodest celebration, of love and poetry and joy, as well as a further addition to the definition of Aussie culture. As an example, his view of life in a nursing home is as darkly irreverent as it is comic:

Each day comes and each day goes,

the next exactly like the last

with all the shipwrecked sprawled in chairs,

thinking only of the past,

a small Titanic, if you will,

with one great iceberg up ahead,

our buoyancy half-gone already,

the lookout, in a deck-chair, dead. (p.29)

His older readers may not be reassured but they are amused. This latest verse novel also confirms the fact that this award winning writer is ever prolific, since he has now published eighteen collections of poetry as well as two novels, four verse novels and several other works including anthologies, translations and a biography of the jazz musician, Bernie McGann.

Except for Lawrie Wellcome who appears in Coda for Shirley only in memory, the characters from that previous verse novel carry on in this new narrative, one that is again unique in theme and narrative style. Each member of the cast is memorable and sharply drawn and the situations and antics in which Geoff Page involves his characters are fun to read or hear (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EmsniQUuDKw ). His stars may not be young, but I appreciate the way they remind us that uproarious life and love and sex do go on after 60 or 70 or even 80. The memory of Shirley’s affair with Lawrie and his caresses wafts musically throughout this book:

that sweet cadenza to his life

a duet only love can sing – (p.4)

Geoff treats his characters tenderly and with affection so they charm or intrigue their readers. No euphemism here; the characters are all too honest, human and multi-dimensional. Shirley, ten years on from the first verse novel, is still witty, passionate and insightful in regard to herself and those people she loves. The action in Coda for Shirley revolves around her final will or coda and the way, in life and after death, she is determined to enforce her wishes on her daughters, Sarah and Jane. It was these errant progeny who tried to undermine her relationship with Lawrie, her great love, while Sarah’s children, Shirley’s grandsons, supported that relationship. There’s irony in the way she settles her possessions and those who inherit them. The book begins with Shirley’s voice, idiosyncratic and always amusing. She sets the scene, reminds us of past events, and introduces the other characters. While she may concur with Geoff Page about matters such as rhyme and metre, she’s very much her own woman.

Coda for Shirley has three sections and three sets of voices and each tells one version of the story and gives a response to Shirley’s coda. The book begins affectionately and directly and with some mystery:

Dearest daughters, Jane and Sarah,

You’ll read this only when I’m dead.

I’ll leave it with my cheerful lawyer

who, with her very well-trained head,

has seen how things might be arranged

when I am truly ‘done and dusted’,

about what goes to whom and who

might, at the end, be truly trusted.

The language seems clear and unambiguous but there are layers and certainly a hint of what’s gone on before. ‘Trusted’ gives a firm ending to the stanza but it’s also quite suggestive. And I like the collusion of ‘cheerful’ with ‘when I’m dead’. It does set a tone for the book and its author’s attitudes to life and death. The poetic lines of the first section reverberate through the second as Shirley’s dearest but unsympathetic daughters, Jane and Sarah, come to grips with their loss and their mother’s wishes:

The funeral was bad enough;

their mother’s poetry is worse,

reciting all their ‘failures’ via

the rigours of accented verse.

There’s some resolution in the moment when they finally accept that perhaps Shirley’s affair with Lawrie Wellcome may have been more positive that they previously wanted to believe. I like the way Geoff Page takes time for transformations and affirmations in this verse novel:

They stop a moment; both are smiling,

There’s not a smidgeon of chagrin,

They strike their glasses once together.

‘Here’s to Shirley’s “year of sin!”’

The characters from the third section who take the novel into the future are Shirley’s grandsons Giles and Jack. In the previous verse novel, Lawrie & Shirley, they were sent by Sarah as shock troops to remind Shirley of her grandmotherly duties. Even as teenagers they were smart enough to see that love is not only more important, it had made Shirley happy and more beautiful. Now, having retreated from their parents expectations of ‘law and med’ they are working, each in their own ways, to improve the world. They seem to be as clear-sighted as Shirley and to have been blessed by the terms of the coda that so annoyed their aunt and mother:

‘Correct,’ says Giles, ‘but in proportion

it’s mainly down to Grandma Shirley.

She left her money straight to us,

not worrying about how surly

such a move would leave her daughters.

She knew how it would leave them numb,

those two up-market girls of hers –

one of whom is still our mum. (p.74)

So the book begins with mystery then sings and plays through three generations before it ends with joy and hope for the future. There is whimsy and rhyme and rhythm but also irony. There is death here but it not tragic and comedy overcomes any negative moments. Geoff Page’s character studies are, as Peter Goldsworthy remarks, ‘scalpel-sharp’ and his characters are always entertaining. They made me want to go back and read the first and connecting verse novel: Lawrie & Shirley. Geoff’s second verse novel is satirical and can, at times, show us life’s shadows. But it is such fun to read. Coda for Shirley is a celebration of life, love and a distinctly Australian way of speaking and thinking.

May 17, 2012 / mascara / 0 Comments

Ali Alizadeh’s most recent books include Ashes in the Air (UQP, 2011) and Iran: My Grandfather (Transit Lounge, 2010). With John Kinsella, he has edited and translated an anthology of Persian poetry in English, which is forthcoming in 2012. Ali is a lecturer in Creative Writing at Monash University, and has a website: http://alializadeh.wordpress.com/

Ali Alizadeh’s most recent books include Ashes in the Air (UQP, 2011) and Iran: My Grandfather (Transit Lounge, 2010). With John Kinsella, he has edited and translated an anthology of Persian poetry in English, which is forthcoming in 2012. Ali is a lecturer in Creative Writing at Monash University, and has a website: http://alializadeh.wordpress.com/

Words

I can’t find my phone. Plato

couldn’t find the Beyond, denounced

Word vis-à-vis Voice

as inherent poison. This weekend

the planned occupation of Melbourne

by activists, to announce the end

of ‘corporate greed’. I dial a number

and burn the Other’s ear with irony

of hidden envy. No, Word isn’t

the perpetual deferral of a signified. Void

is Truth misnamed, a-voided. ‘Greed’

the very tip of the most visible iceberg

of Capital’s glacial matter. I can’t

stop talkin’, talkin’, don’t care who’s hearin’

the repetition of unfulfilled urge; tomorrow

a song may ‘unite the human race’. Marx

the only dead thing I can’t speak ill of

(who hasn’t sensed a ‘spectral’ Real?)

which makes me hang up the phone. Use

written words to formulate the unspoken

and the unspeakable. Yes, I’m out of credit

and too stingy to finger the alphabet

and text-message bored friends. Capital

-ism may be its own undoing.

Thus Capital

Capital is the Real of our lives.

—Slavoj Žižek

I’m here for an encounter

with Power. Can’t accept It

has nothing to offer but ice-cream

and pink lingerie. I prowl the mall

to catch Its sordid eye. Never mind

the sales, reduced symptoms

disguised as fetish. What haven’t I

disavowed? I’ll serve in the society

of disrobed spectacles. I’ll see

the naughty bits. Ethical consumers

fumble with fig leave; not fair

trade indulgence, what I seek. I aspire

to bow before Its grisly form, kiss

the slimy rings on the all-too-visible

hand of a festering market. Then relish

the stench of Its anus. So free, so real.

May 5, 2012 / mascara / 0 Comments

Lindsay Tuggle’s poetry has been published in HEAT, commissioned by the Red Room Company, and included in various journals and anthologies in the US and Australia. In 2009, her poem “Anamnesis” was awarded second prize in the Val Vallis Award for Poetry. In 2012, she is the recipient of an Australian Academy of the Humanities Travelling Fellowship. Lindsay grew up in the Southern United States, and migrated to Australia eleven years ago. She now lives in Austinmer, where she is working on a book of elegies.

Lindsay Tuggle’s poetry has been published in HEAT, commissioned by the Red Room Company, and included in various journals and anthologies in the US and Australia. In 2009, her poem “Anamnesis” was awarded second prize in the Val Vallis Award for Poetry. In 2012, she is the recipient of an Australian Academy of the Humanities Travelling Fellowship. Lindsay grew up in the Southern United States, and migrated to Australia eleven years ago. She now lives in Austinmer, where she is working on a book of elegies.

The Arsonist’s Hymnal

wake to see if the trains are still running.

the beloved ones coalesce

in the gloaming,

almost persuaded.

in the afterglow of mall glut,

her veiled alien

hastens farther down

this last bathed hall.

have you seen the vapors?

all dead arrive

unborn as lighthouses.

our eldest unfurled below

the stairwell under the baptistery

elevated as a drowning chamber

whose guests have vanished.

her alias is stark. loose-limbed.

summer is almost a covenant.

before darkness

she’s intent on devouring parables.

all others fall away

the consequence of habitual neglect.

ghosts die without ceasing;

guard trendsetters against

the perils of walk-in-closets.

as soon as she’s finished washing her hair.

her materials form only metric tongues.

with solemn vigilance

we can’t be seen

underwater

echoes are laughter.

only these rituals endure:

all night in dreams he sets fire to her eyes.

Anamnesis

1.

She dreamed a cemetery of glass tombs.

The perfume bottles were her favorite.

An estuary arsonist

(eluding self-harm):

she refuses to bathe alone.

River viridity is dangerous:

Honey locusts ghost the salt baskets.

Despite coastal housekeeping

tidal mouths breed

vertical striations.

Nutrient densities render her blind,

hysterically.

Language is no longer a nomenclature.

Even her humming has meaning: a kind of

swirling guttural echo.

Something you knew once.

Thoughtless recovery

(habitual)

swarms against the sane

familiarity of lawnmowers,

the creeping grace

of unseeing.

2.

From New Madrid gully inland

we remember the day

the river flowed backward.

In the absence of coherent levees

shifting glacial loess

an unknown number drowned.

The measure of loss

is in the submergence of trees.

There’s an upside to angularity.

Sharpness invites reconstruction.

The moral is integral burial:

illiterate confinement

supernatural as filth.

3.

The madness of trees

ringed in brackish immersion.

Roots mark intervals

of barren impermanence,

hoard pollen traces

in vanishing silt.

The delicate erosion

of Kalopin’s eyes:

residual gladitsia in

backwater muck.

She’ll kind of ramble beautifully

her laughter like bells.

Water collects in

pockets of collarbone.

Divers burn in shallow

basins. One hundred

years later we hunch in

the elongation of aftermath.

She becomes fishmouthed

the obsession of swallowing

written beneath the soles of her feet

another angling glaze.

Assemblage data reveals

a cedar arboreal influx.

Lower soil analysis shows

ragweed is rare or absent.

Cicadas are reckless breeders.

Its been dry for so long here

we made ourselves gowns

from this dust.

Wake.

How to capture

the unison language

of insects?

She’s haltingly fluent

in the vanishing tendency

of the object

where descent

is watery and burns.

An acrid metallic sound,

translated, roughly:

The wet are pretty.

All this

beckoning comes at a cost.

Author’s Note:

This poem responds to two bodies of water in western Kentucky—an area called Land Between the Lakes. The first was formed by a series of earthquakes from December 1811 to February 1812. The second was created following the floods of 1937, and gradually expanded for the dual purposes of flood control and hydroelectric power. Many towns and farms were flooded and relocated. Some residents refused to evacuate, and drowned.

Dark Night Walking With McCahon

Dark Night Walking With McCahon