May 29, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

Ella Jeffery’s poetry, reviews and essays have appeared in Meanjin, Westerly, Cordite, Best Australian Poems and others. She won the Meniscus/CAL Prize for Best Poem, the June Shenfield Poetry Prize and was shortlisted for the Val Vallis Award. She lives in Brisbane and tweets from @JefferyElla

Ella Jeffery’s poetry, reviews and essays have appeared in Meanjin, Westerly, Cordite, Best Australian Poems and others. She won the Meniscus/CAL Prize for Best Poem, the June Shenfield Poetry Prize and was shortlisted for the Val Vallis Award. She lives in Brisbane and tweets from @JefferyElla

the ferret population of shanghai: some anecdotal evidence

my friend says ferrets

roam the streets

they were released a long time ago

to catch rats or perhaps it was

roaches he says

now they thrive in back alleys and stairwells

the thresholds of people’s lives

he says they’re called yòu

or perhaps it’s māo yòu

and you can see them at night

on sinan lu where dozens of men

are re-cladding the houses

most mornings workers drip

like melting ice from the neocolonial eaves

hanging neon signs in english

the old tenants shuttled

to some outer orbit

i am doubtful

of most of my friend’s stories

and of this loose grip

on language: mine

and his

either way

the rats and roaches are still out there

but some nights riding

home late

I think I see white ferrets

streaming

under the gates

and into those houses

where nobody is allowed to live

Mutianyu in June

Clouds in the west

tinged the freak green of hail.

There was nobody around.

I walked for hours along the wall

and now and then I’d run

into other people in twos or threes.

We nodded at each other in our plastic

raincoats. For ten minutes

I watched a wild donkey

stand in the rain

among the trees below.

Fog pulsed through watchtowers.

Sometimes the steps

were far bigger and further

apart than I am used to.

Sometimes they were so small

and steep I lifted my whole

body on the balls of my feet

and laid my hands

on the rain-slick steps

above and pulled myself upwards,

scraping stone with my knees

and ankles and shins, bones

I thought I had outgrown.

May 29, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

Michelle Cahill’s short story collection Letter to Pessoa won the NSW Premier’s Literary Award for New Writing.The Herring Lass is her most recent poetry collection. Her poems have appeared in Poetry Ireland Review, Meanjin, Island, Antipodes, Best Australian Poems and the Forward Book of Poetry, 2018. She co-edited Contemporary Asian Australian Poets with Adam Aitken and Kim Cheng Boey, and Vagabond’s deciBels3 with Dimitra Harvey. With Professor Wenche Ommundsen she was a University of Wollongong conference delegate at Wuhan University’s 2017 ‘China: One Belt, One Road.’

Michelle Cahill’s short story collection Letter to Pessoa won the NSW Premier’s Literary Award for New Writing.The Herring Lass is her most recent poetry collection. Her poems have appeared in Poetry Ireland Review, Meanjin, Island, Antipodes, Best Australian Poems and the Forward Book of Poetry, 2018. She co-edited Contemporary Asian Australian Poets with Adam Aitken and Kim Cheng Boey, and Vagabond’s deciBels3 with Dimitra Harvey. With Professor Wenche Ommundsen she was a University of Wollongong conference delegate at Wuhan University’s 2017 ‘China: One Belt, One Road.’

Forbidden City?

Morning is shuttered and we are like dormant fireflies

at the river’s edge, pale sky, the dainty fruit of miniature

orange blossom—say I’m not banished, then block me.

Texting isn’t my dialect tho I want your revolving heart.

And how little I would want to lose the scent of your hair

brushing fingertips with a Princess from the provinces.

Confess I have been using Express VPN; it’s pretty good.

You said Shakira’s ‘Don’t Bother’ wasn’t your type.

You definitely have a love-hate relationship with my body.

The river is a dark filigree in moonlight; the library at

the Pavilion of Literary Profundity has black, watery tiles.

All the other roofs are yellow, but how green is the Prince?

Night vendors of silk-worm cocoons and sea horse kebabs

take cash or WeChat credit, opium poppies blousy the lake.

Jian bing for brekky; soy ‘n egg-smeared coriander flakes.

They crackle, gag, feet bound, legs tied back, the sous-chef

in the galley is masked, serving mussels, steamed oysters.

After thin-wheeled bicycles, pink southern lychees, a court

seals the probate, painted fan, calligraphy of sweet lies.

May 25, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

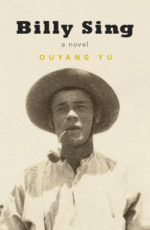

Billy Sing

Billy Sing

by Ouyang Yu

Transit Lounge

ISBN: 978-0-9953594-4-4

Reviewed by BEIBEI CHEN

Born in 1886 to an English mother and Chinese father, William ‘Billy’ Sing and his two sisters were brought up in Clermont and Proserpine, in a rural part of Queensland. Sing’s father was a drover and his grandfather was a Shanghai gold digger. Sing was a sniper of renown during Gallipoli war, his life has been remembered in both literary works, social media and an ABC TV mini-series, The Legend of Billy Sing. However, Billy’s Chinese ancestry, failed marriage and haunted war memories had not been fictionalized until Ouyang Yu published his novel, Billy Sing, in 2016.

It is probably the diverse racial perspectives and rich cross-cultural experience that drive Ouyang to write on this well-known but complicated historical figure and produce a new version. The story of Billy Sing in Ouyang’s eye is penetrating and darker, unsettling a renowned Chinese Australian sniper’s legendary but troubled life. In a sense, as a gifted writer, Ouyang flips the other side of Billy’s coin and finds the undiscovered part of him as a tragic heroic figure. Billy Sing is arguably Ouyang’s most successful literary novel. It is noteworthy for its prose-like narration, the bold imagination of Billy Sing’s private life and the way it illuminates themes of transnational identity and memory.

In Billy Sing, Ouyang utilises the Chinese cultural perception of “being a hero.” In Chinese culture, a hero has two faces: being honoured and worshipped in front of the public and being miserable and troubled in the private life. Billy Sing has the two faces and since many of the records have caught the first face, Ouyang smartly chooses to focus on the second.

The novel begins with a conflicting and unpleasant conversation indicating the troubled identity of Billy Sing: his friend Trevor mocked him by reciting “Oh, you cheap Chinaman, Chow, Pong, Ching-Chong, Choo-Choo, Cha-Cha, Wah-Wah, half-caste, mixed blood…” (13). Though historians may argue that there is no record of Billy Sing in history being bullied by white Australians the incident makes for a provocative fictional beginning for the novel. From the very first page, Billy’s identity is constantly at stake throughout the whole book.

Ouyang portrays Billy as a boy living in two conflicting cultures even as he grows up in Australia. As a teenager, Billy is deeply influenced by his father, a Chinese man who is always aware of the cultural dilemma of Chinese Australians, especially the second-generation migrants: “You were born of two truly incompatible cultures and languages, as incompatible as fire and water.” (19) Carrying life on with a doubled identity, Billy grows up to be a sensitive and confused self: “I constantly heard a voice saying to me: ‘You are no good mate. You are neither here nor there. You should have been born elsewhere. You were wrongly born. You were born wrong’ ” . (31)

Regarding himself as a “wrong” person does make young Billy feel hyper-sensitive and easily provoked. Tired of dealing with the angry moods triggered by drinking or gambling, he decides to enlist as a soldier, to fight for his adopted country. However, though regarding himself as an Australian, some of his fellow people despise him for his mixed blood. A Chinese saying goes like this: “Wars produce heroes”. Billy surely deserves the title of “hero” for his service in Gallipoli for Australia, his “father country”. But Ouyang digs further and darker: what war brings to Billy is endless trauma and haunted memories; memories which eventually bury Billy together with other soldiers in the grave of loneliness. After the war, Billy has to admit that “to save myself and my comrades, I had to kill and kill well.” (79) According to Sing’s inner monologue, it is obvious that his attitude towards war is quite negative: “We are all from elsewhere, originally at least, and are here killing total strangers who did nothing wrong”. (80) In the novel, his brave deeds of shooting enemies do not bring him pride. Instead, he thinks he is murdering innocent people — a killer rather than a hero. While history remembers Billy Sing as a war hero, this book challenges the notion of nationalism and portrays Billy as a person who detests war and death. He mocks himself: “my life had always been full of death, and success. Death and Success. Death Success. Deathuccess.”(99). Medals do not symbolize national pride, rather, they remind Billy of all the trauma haunting his subconscious.

The nightmare-like memories of killing, fighting and burying constantly challenge Billy’s after-war life and his perception of Australia is also transformed. Being a Chinese Australian, discriminated at by his peers, Billy cannot form a permanent sense of belonging, but during the war, his attitude is transformed: “If I could, I’d shoot the lot, end the war and pack up for home.” (82) He also has nostalgia towards the “kangaroo country” and the ideal life would be “shooting the roos and eating them, enjoying the waters when they rose each summer”. ( 91) Ouyang naturally merges Australian vernacular into the story of a marginalised Australian soldier. Numerous complex sentences are used to describe Australian bush scenes; killing kangaroos becomes a warm-hearted dream job, adding this novel more Australian flavour compared to Ouyang Yu’s other novels such as The English Class or The Eastern Slope Chronicle.

But when it comes to Billy going back with his wife Fenella, the plot is twisted by another difficult knot: Fenella is from ‘‘a family of non-blue-blooded Scots’’ and is reluctant to move to “the convicts’ country” even it is also a white world peopled with Anglo-Celtics. Ouyang’s thematic argument is that no country is free of discrimination simply because humans like to create divisions that exclude some people from belonging. At each occasion when Billy may find a “closure” to the ambivalence of his “shaky identity”, he is challenged again by his wife’s unwillingness to live in Australia. For a revenant like Billy, there is never an easy “going back”, because while battling with the uneasiness of being surrounded by ‘‘battle-worn and battle-maimed soldiers’’, he has another battle of living with a wife not keen on Australia.

On the subject of “home”, Billy has a fierce argument with Fenella: he regards Australia as a place where he has “peace and quiet” but to Fenella, Scotland is her home and “Nothing Australian is comparable”. (119) Billy feels shocked by Fenella’s denial of living in Australia and he also realises that to assimilate Fenella into an “Aussie” identity is nearly impossible. Billy is torn between the choice of returning to Europe where old memories haunt and harass him or to let Fenella go and he carries on with his life in “homeland”. Eventually, Billy Sing realises that his identity as a war hero cannot earn the respect of his wife; that for Fenella, the received stereotype of a degraded Australia cannot be easily shaken.

By unsettling the transnational marriage between a war hero and a Scottish girl with excessive national pride, Ouyang Yu transposes the issues of “national identity” to a world context and makes readers think about how seemingly straightforward questions. Though it is a slim novel of only one hundred and thirty five pages, Billy Sing certainly rediscovers a remote history and offers dynamic energy and tragic beauty. As a Chinese Australian male writer Yu’s voice helps to retrieve from the archives a delicate and lonely soul. Billy Sing, considered as a “heroic figure” is doomed to be a lonely man “persisting in his solitude”.

By indications in this book, Ouyang drives readers to predict that Billy Sing, a “killer”, “a murderer” and a “hero” has to live in the endless trauma and solitude, which leads to the ending of his tragic death in his beloved “country” and “home”. The reasons are obviously complicated: individual identity crisis, unhappy marriage, and racial discrimination. But fortunately, in this book, we sense humanity, and we sense the power of writing: to change history into a touching “his ‘story’”.

BEIBEI CHEN is currently working at Eastern China Normal University in Shanghai. She obtained her Ph.D degree from UNSW, Australia in 2015. She is a poet, literary critic and translator.

May 25, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

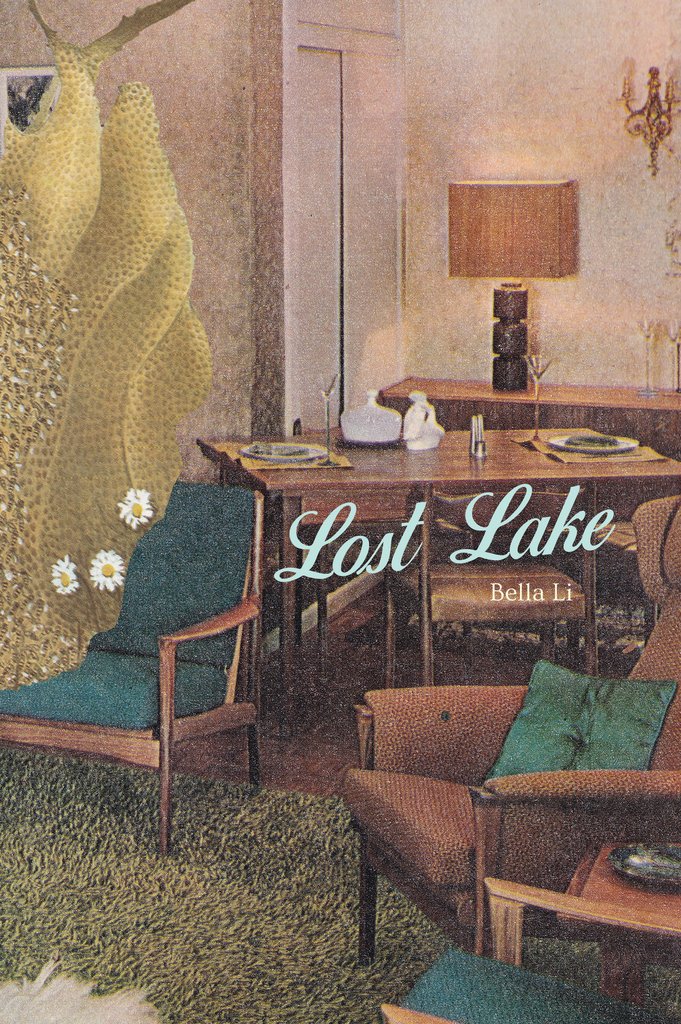

Argosy and Lost Lake

Argosy and Lost Lake

by Bella Li

ISBN 978-1-922181-96-1

ISBN 978-1-925735-18-5

Vagabond Press

Reviewed by JENNIFER MACKENZIE

A publishing highlight of 2017 was the appearance of Bella Li’s Argosy, and this has been followed by the recent release of Lost Lake. By introducing an intriguing blend of collage, photography and sparely-written text, the poet has provoked, as well as enthralling us with her original poetics, a fresh way of looking back on some poetic traditions, particularly that of Surrealism. Although a number of responses present themselves for discussion, I shall focus on what is a dominant focus in both collections, that of the journey. With the theme of voyages or journeys reverberating through Argosy and Lost Lake, they reveal themselves as an imminence, in which all images and words surrender into an inevitable beauty.

It is apt indeed that the principle poem in Argosy, Perouse, ou, Une semaine de disparitions, connect the maritime expeditions of La Perouse to the collage novels of Max Ernst, these being Une semaine de bonte: A Surrealist Novel in Collage, and The Hundred Headless Women. The voyages of such explorers as La Perouse and Bougainville were a major inspiration for several French writers in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In prose, Balzac, Flaubert and Proust come to mind, and in poetry the influence appears considerable when we think particularly of Gautier, Segalen, Baudelaire and Rimbaud. Rimbaud, with his notorious and basically unrecorded escapade to the then Netherlands East Indies provided in A Season in Hell, a picture of the endgame in colonial domination : ‘ the white men are coming. Now we must submit to baptism, wearing clothes, and work’(1)

Apollinaire, one of Li’s sources in Argosy, coined the term ‘Surrealism’ in regard to the ballet Parade, created for the Ballets Russes in 1917 by Massine, Cocteau, Picasso and Satie, a ballet in which disruption of surfaces and sound, with noise-making instruments and cardboard costumes, confounded aesthetic expectations. As Surrealism developed in both literature and art, Max Ernst led the way with his collages, so integral to the method in Argosy. The artist described the technique as ‘the systematic exploitation of the accidentally or artificially provoked encounter of two or more foreign realities…[to bring about]…a hallucinatory succession of contradicting images’.(2)

What Li has achieved in Argosy is quite remarkable. In La Perouse, the voyage is depicted as hallucinatory, a collage of surrealist dreamscapes, of oceanic encounters which liberate the ekphrastic from its often reproductive impetus. With language taken out of its temporality, an archaic texture creates its own spatial idea and its own measure. At this point, I would like to refer to Ernst’s technique of frottage, where as the artist stated ‘the boundaries between the so-called inner world and the outer world became increasingly blurred’. There is a sense in the restraint in the use of language in Argosy, in the deft rise and fall of the poetic line, in the masterly control of phrase and silence, that the measure itself delineates erasure, delineates trace.

It is fascinating to see in Argosy how collage and text situate each other, not as complimentary or elucidatory, but as transforming the actual experience of reading and of viewing into the poetic intention. The collages, with their gargantuanism, their contrast between the splendour of the discovered and the sometimes small scale of the discovering, the extensive use the avian directly inspired by Ernst, play on the monstrosity of the quotidian. To quote from the text seems something of a travesty, considering how well the sections knit together, but in jeudi: Les reves we are immersed in the experience of the speaker, the measured voice containing a flourish of an image, Our man at the helm, broad-shouldered and in love, suggestive of other worlds that remain unspoken, or only hinted at:

This day we sail, dividing the waters from the heavens. I am

my own guide, the steerage, the hull. This day by sea, by the

sea we lie. Sharp peaks divided, three by two by three. Our

man at the helm, broad-shouldered and in love, saying: This

but not this. This, but not this.

You ford the stream. You move. (52)

And in the final text section, samedi: Les incendies, there is a sense of fatality and an acceptance at the end of a journey which always portended the abyss:

In the perilous passage, prepare for death.

Though tempests rage, take shelter in fate.

At every harbour, seek solitude and rest.

Through sickness and sorrow, find solace in faith.

On days of fine weather, breathe and drift.

When evening comes, set fire to the ships.

Everything lies. Everything lies to live.(84)

Before that, in what is one of the most telling passages in this section, we find La Perouse, with his companion M. Lavaux, looking down into what seems the very essence, or being, of the world:

Morning on the dim shore, hours coming and going. We step

down, M. Lavaux and I, to the water’s edge. Mirror of the

world as it dips and slides from view, wave beginning its slow

path to infinity. There we discover the first of the objects, of

which I will relate only. The barest details, ashen. Though the

day will begin and begin again. Though we meet, he and I, with

no sign of land. Circling, in the upward draughts, a curious

sight: Buteo buteo. Buzzards, so far south.(79)

This seems to be a good point at which to turn to Lost Lake, which displays a further development in the integration of image, text and theme. Sourced texts resonate through the poetry, which raises some interesting questions about how we read, about how images resonate or reside within the imagination. Recently I attended a talk given by the artist John Wolseley, during an exhibition of his work at the Australian Galleries in Melbourne. At one point, he was discussing the importance to his own work of Max Ernst and his technique of frottage, of how the technique enables both erasure and emergence, that an image may ultimately reveal itself as if from the beginning of time. In Lost Lake the language does something comparable, as it is deliberately set out of context or any quotidian reference, having a tone placed somewhere between the Bible and Calvino. In relation to the way photography and text play into this field, especially in terms of natural imagery and this veering to the origin, a comparison could be made with the cinema of Terrence Malick, where the voice, spoken into the creative space rather than being merely perceived as dialogue, forms an imminent connection with it.

At the same time, however, this seemingly shared method stresses the isolation, the ‘out-thereness’ of everything. Such a sense can be found in the sequence Confessions. Eighth is a stellar example of this intent:

That the entire forest was plunged as though under a sea. As

at the beginning of the world, as if there were only the two. So

was I speaking when – with a more premeditated return, with

more precision, as though upon a crystal glass- I asked my

soul why she was so. Over the forest did my heart then range.

I shut the book. And I cannot say from which country, which

time, I cannot say from which it came. (44)

Also in Confessions, in Sixth, there is a hint of Zen:

There are sounds I do not hear. Sometimes, at the edge of

water and surrounded by trees.(43)

and in Second, there is an apprehension of home, but also not-home, that dwelling is but an absence, a shadow:

That what I have seen I have seen from houses. That in my

father’s house was a strange unhappiness. That I had searched

for it, in my life, in the hollows of doors, that I had found it,

that it had found in my home. And in my home I had neither

rest nor counsel. The days, the soul of man riveted upon

sorrows; now and then the shadow of a woman, in the far

corners of the house.(41)

Grand Central, in a stunning series of images, presents another form of the journey, this time by rail. The poem brilliantly situates composer Steve Reich’s composition, Different Trains, where his wartime experience as a child of regularly shunting across the United States, splices with the European temporality of Hitler’s death trains. Lost Lake concludes with the luminous sequence The Star Diaries. The journey/s and its/their destinations are varied and unsettled. Home is unattainable, but the journey continues in dystopian fashion. One thinks of the sourced Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, but also the work of that one-time Surrealist, Rene Char. Presences appear and vanish like a shadow as in The Eighth Voyage:

… I must have been ill because I can’t recall. But I remember him

standing there in the shadows of the firelit room, barefoot.

Calling me by my name. In the following weeks the radiation

decreased, a slow bleeding away. Then the quiet zero weather

broke. And we continued – me one way and him another.(134)

Further on this sequence in the vision becomes apocalyptic:

…Drifting over former

libraries and museums, all sunk beneath the jelly-green water.

The old scow navigated, under a white moonlight, past ghostly

deltas, luminous beaches; each in their turn submerged and

sinking. Overhead, dusk was vivid and marbled. Clouds of

steam filling the intervals between buildings, motionless and

immense; silt tides accumulating in dense banks beyond th

concrete reef. Darkness fell. In the surrounding suburbs the

streets were filled with fire until four o’clock.(135)

The textual sequence ends with a statement of record in The Twenty-fifth Voyage:

I am obliged to give an account of what I saw: a moving

walkway, slowly unreeling. On the ocean surface, something

moving. Something looked like a garden; I recognised an

apiary. Sometimes seemed to be standing upright, sometimes

lying on its side. There occurred a magnetic storm and the

radio links were cut.(151)

The Twenty-eighth Voyage presents a vision of a conservatory.

Both Argosy and Lost Lake are beautifully presented and designed. They are a pleasure to look at and to hold, and both collections raise as many questions as you may care to ask.

NOTES

1. Translation by Jamie James in his Rimbaud in Java, Editions Didier Miller, Singapore 2011, 69

2. Quotations from Max Ernst in www.modernamuseet-se>max-ernst

JENNIFER MACKENZIE is a poet and reviewer, focusing on writing from and about the Asian region. Her most recent work is Borobudur and Other Poems (Lontar, Jakarta 2012).

May 25, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

Jee Leong Koh is the author of Steep Tea (Carcanet), named a Best Book of the Year by the UK’s Financial Times, and a Finalist in the 28th Lambda Literary Awards in the USA. He has also published three other books of poems and a book of zuihitsu. Originally from Singapore, he lives in New York City, where heads the literary non-profit Singapore Unbound.

Strongman from Qinshi Huangdi’s Tomb

The head would have given the final expression

like a peacock’s tail feathers, had we not lost it,

and yet the body is too strongly modeled for us

to require a face. Rounded like high cheekbones,

the shoulders weigh two brawny arms, snakes

lashing within, holding what would have been

a great bendy pole, with a colleague, on which

an acrobat would swing and somersault and land.

Driven to the ground but rising from his feet,

the enormous torso, of earth once trampled on

by trumpeting beasts, is not smooth like a smile

but frowns with clear cracks, in large fragments,

about the roof of the barbarous belly, the lines,

opening and closing, emanating from our mouth.

California

Arnie has no more

devoted follower

than Olympus Chan

from Guangzhou.

For at least a year,

between fifteen and

sixteen, he went so

far as to put on

the Austrian accent.

Trained and won

Mr. Universe at age

20, same age as Arnie.

Moved to Hollywood

to be in the movies.

Had his big break

not as Conan, but

Young Confucius,

breaking his opponents’

jaws when they did

not heed what he said.

Grew rich selling

herbal supplements,

grew famous too.

Then the ultimate

test, the gubernatorial

contest, he loved

saying “gubernatorial”

with a Cantonese

twang, which he won

handily against the

El Salvadoran, on the

back of a huge Asian

turnout, and not a few

El Salvadorans, at last

striking gold as Asian

American and universal.

May 25, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

Timothy Yu is the author of the poetry collection 100 Chinese Silences, an editor’s selection in the NOS Book Contest from Les Figues Press. He is also the author of three chapbooks: 15 Chinese Silences, Journey to the West, and, with Kristy Odelius, Kiss the Stranger. His writing has appeared in Poetry, The New York Times Magazine, TYPO, and The New Republic. His scholarly work includes Race and the Avant-Garde: Experimental and Asian American Poetry since 1965 (Stanford) and an edited collection, Nests and Strangers: On Asian American Women Poets (Kelsey Street). He is professor of English and Asian American studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA.

Chinese Dream 25

Timothy dredged, half-heartedly, for stories

of the past Timothy, his mute inglorious

present, and his worries,

all the bright heels he stamped— —Paranoia,

Mr. Chan, paranoia. You imagine all!

—Hands off my cabal,

designer fashion. All dressed for the ball

slender & bound Timothy. Mark him please.

Tender him breathless,

and burn at high rate his surplus resentments:

nourish his need. Remake him as our sentiments.

—My Chan, you no speak.

—I cannot forget. I am wasting away.

There is nothing in my dreams. I’m not the girl

who fought and sang.

Everyone loves a liar, a picture unhung,

lashed to the post at bedtime. Nothing stays.

I owe you everything.

Chinese Dream 31

A Calcutta banker instructed me a little in Yoga. I achieved the free lotos position at the 1st try.

—Berryman

Timo Timoson, from Wisconsin,

did a white man play,

in his tweed jacket and a choking necktie

cuttin his teeth on Buddha, soft man-breasts,

and gave his body one yoga twist;

admiring himself he withdrew from his true

‘murican nature an Oriental smile

& posed a lotus.

Timothy & Henry, each other’s impostors,

in the word-kitchen cook a blankface play

for the lacerated stage; the curtain rose

on the foolish chink and his white-chalk knees

Timo Timoson, from Wisconsin,

did a playing white man play

who even more obviously than the still fantastical Asian American

cannot be himself. Others don’t exist,

human beings in general do not exist,

outside his stare.

May 21, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

May Ngo is a researcher in the social sciences, focusing on development in Cambodia. Her other interests include theology, migration, diaspora and literature. She is also developing her father’s memoirs of his time with the Vietnamese communist army as a novel. She has a blog at The Violent Bear it Away (https://theviolentbearitaway1.wordpress.com/) and tweets at @mayngo2

May Ngo is a researcher in the social sciences, focusing on development in Cambodia. Her other interests include theology, migration, diaspora and literature. She is also developing her father’s memoirs of his time with the Vietnamese communist army as a novel. She has a blog at The Violent Bear it Away (https://theviolentbearitaway1.wordpress.com/) and tweets at @mayngo2

Little Red Book

In the Chinese school Chen attended, in a medium-sized port town in South- Eastern Cambodia, their reading books had bright red covers, yellow stars and a picture of Mao’s shiny, round amiable face smiling up at them. In order to reach his school Chen had to take a ferry everyday across the murky brown Mekong, and in class he learnt lines from Mao’s wisdom, crystallised into songs he and his classmates would sing, their voices harmonising and occasionally breaking out of harmony. The songs they sang hailed being on the side of the poor, called to make the world equal:

The east is red, the sun is rising.

From China comes Mao Zedong.

He strives for the people’s happiness,

Hurrah, he is the people’s great saviour!

Chairman Mao loves the people,

He is our guide

to building a new China

Hurrah, lead us forward!

Chen would sing in a loud, pure voice, memorising whole passages from songs printed in their little red books. In class, they would listen to the crackly radio broadcasting all the way from Beijing’s central radio station, calling for the uprising of proletariats all over the world, calling for workers to unite to create a happy paradise where there was no difference between the rich and the poor.

His teacher, Mr Xi, wore a badge with Mao’s face in silver profile, and as a daily classroom ritual read a passage from one of Mao’s works. He would stride with his long legs up and down the length of the room and in a raised voice read a selected excerpt for that day, only pausing at particular moments when he wished to highlight a passage to his students, peering at them intensely through his glasses. Chen idolised Mr Xi. And on the wall at the front of the classroom, prominently hung the obligatory portrait of the King of Cambodia, Sihanouk; his broad, round face, serious eyes and the hint of a smile looking down at them.

Once, they had a visit from someone Mr Xi introduced as Mr Bao Li. Chen did not understand who this man was or what he did exactly, except that Mr Xi said that he was important. The man looked like he was in his twenties, dressed in neat, ironed clothes and a straight cut fringe that ended just above his eyes. He gave a presentation to the class, a rather long and winding talk that included communist revolutionary theory and patriotism and ideals. Although some students started to fidget and move their legs, pushing their pens and paper around on their desk, Chen listened attentively. In that small classroom, dusty and filled with the standard wooden desks and chairs, his world widened to include all the poor of the world, the down-trodden and spat upon. He could imagine, more than imagine, feel what it must be like to be one of them. And also what it would be like when liberation finally came.

“Not to have a correct political point of view is like having no soul”. Chen took to heart this line in Mao’s little red book, and in his final year of school when Chen was chosen as leader of his class he organised a political study group that focused on the book Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung. He selected the chapter on ‘Political Work’ to start with as he found it particularly inspiring with its call for everyone, intellectuals, students and soldiers alike, to be involved in political work. His best friend, Kiet, was also in the study group. Kiet was a gangly young man, who, although tall for his age—as he had always been, since childhood—had a desperately youthful looking face with stringy black hair that always fell into his eyes no matter how many times he swiped it away. Kiet’s father owned a successful catering business for weddings and special events, and their families had known each other since both were little. One of their favourite past times together was playing table tennis. Both were agile and quick on their feet and the ball zipped between them like lightening.

Chen and Kiet debated with their classmates on a number of political events and current affairs, they particularly argued against those in the study group who were ambivalent about Western imperialism and its effects. Chen could not understand how one could be a communist and not be against it unequivocally, particularly against what he saw as the biggest beast of all, the United States. He and Kiet wrote articles in this vein and hoped to get them published in the local newspaper, to this end they asked Mr Xi to help them order books that the school did not have, hungry for more writings by the Chairman. Chen ignored subjects in his class that did not relate to politics, ignored those subjects that did not talk about a future that was yet to be created, that he would help to create. The small concrete building by the edge of the river, his school, became like the blinking beacon of a lighthouse in the night, shining upon hazardous rocks and marking dangerous coastlines to avoid; illuminating the way forward. In the classroom, in the study group, writing political tracts with Kiet, he soaked in the luminescent promise-filled atmosphere at school, but at home it was a different matter.

Chen and his seven brothers and sisters lived in a large two-storey brick house with maids and helpers who occupied themselves with the household chores and cooking. He felt a loathing for the fact that they had a TV, servants and, by far, the biggest house in the neighbourhood, while groups of beggars on the street congregated around their household bins salvaging for food scraps. Even worse than these obvious signs of wealth, Chen was ashamed that his father was a “boss”. Chen’s father owned a fish sauce factory employing ten workers, half of whom were an assortment of uncles, cousins and in-laws, was also the owner of a fruit farm filled with luscious mango, pineapple, longan and jackfruit trees, as well as a whole apartment building in Phnom Penh that he rented out to tenants.

“In class society, everyone lives as a member of a particular class, and every kind of thinking, without exception, is stamped with the brand of a class”. This line from Mao’s little red book burned him. He did not want to be stamped by the class of his family and at the same time he could not shake off the feeling that he was a hypocrite, so Chen retaliated in the only way he knew how. He gave up watching TV. He did not ask for new shoes even when they were starting to wear thin. He refused to eat anything more than what he assumed a farm labourer in his town would eat, ignoring his mother’s pleadings to eat more, pushing yet another plate of food toward him. He wanted to take off his bourgeois milieu like old clothes that scratched at him, that were too tight in places because they no longer fit him.

During Chinese New Year all of his brothers and sisters wore new clothes, the girls with ribbons in their hair and the boys with faces scrubbed clean. Chen refused to wear the bright, shining new clothes his mother had bought for him; the new shirt and pair of pants lay forlornly on his bed. Instead, Chen wore an old shirt that had frayed, hanging threads and some blue pants that he often wore to the factory; one of his brothers told him he looked even worse than the rubbish sweeper who had at least made an effort with a new shirt bought from the central market. When relatives came to the house to visit for the celebrations, he greeted them all in his old clothes, hair uncombed. His grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins politely ignored his appearance, even as he accepted their red envelopes looking like a vagrant. All except Uncle Kong, his father’s younger brother, who was known for not mincing words and who could be counted on to make awkward moments even more awkward. On entering the house and seeing Chen, he exclaimed “Hey, why are you looking so scruffy today?” He grabbed Chen by the elbow. “It’s Chinese New Year for goodness sake!”

Everyone looked at Chen and there was a silence before his mother, who was passing around sesame cookies on a plate, gave a nervous laugh, saying “Oh it’s nothing. Just something he’s going through. He doesn’t want to wear new clothes”.

His father’s face clouded, a dark grey mist passing over his visage, but he did not say a word. His father was a tall, well-built man who carried himself in a way that denoted power and strength, a firmness to his hands. Most of the time he spent at the factory, but when at home he spoke few words. For this reason, most of his children were more than a little afraid of him.

Chen also did not reply and instead moved his arm away from his uncle. He did not expect him to understand; his fat, corpulent uncle working as a manager at his father’s fish sauce factory, ordering the workers about while he sat looking on. In private, after everyone had gone, Chen heard his mother crying in the kitchen, telling their cook Piseth that she did not understand where this came from or why. Chen hurriedly retreated back to his room.

“It is the duty of the cadres and the Party to serve the people. Without the people’s interests constantly at heart, their work is useless.” One day, on his way home from school, Chen bought some fried bananas and roasted peanuts from a street vendor. Once he got home he provocatively notified his mother, who was in the kitchen with Piseth, that he was going to give them away to the poor children who lived in their neighbourhood. Upon hearing this, his mother exploded as if a spring had been released inside her, her hands upsetting the plate of mangoes that was to be an offering to their ancestors in the household shrine.

“What! You care so much about the children out there but what about your own family? Why are you ignoring your own family?” She banged her hand on the kitchen counter twice. “You don’t even care about your own brothers and sisters!” Thin black strands of hair fell in front of her face, thin blue veins showed on her hand that laid on the counter.

“Why should I care about them?” Chen retorted. “They’re selfish. You’re all selfish!”

Chen’s mother’s face seemed to stretch outwards, distorting her features. “You ungrateful little bastard, how dare you speak to me like that!” she screamed at him.

Chen felt the rage rising in him, becoming a heavy fog in his mind. His lower lip quivered. He said slowly and carefully, trying to keep his voice even “I dare because you know nothing and only care about yourself.”

Chen’s mother slapped him. She reached and pulled out a butcher’s knife from the sideboard, its edge gleaming, and waved the knife towards him. “How dare you! How dare you!” she yelled in a high, unrecognisable voice, her hands shaking. Her hair had partially come out of its bun, her arm angled to hold the knife up high. Chen felt in that moment as if she were a demonic spirit, capable of anything.

Chen turned around and ran out of the kitchen, a blur going past Piseth the cook, Serey the maid and his siblings who had come to see what all the shouting was about. He ran out of the house and all the way to the fish sauce factory, breathlessly going straight to the section where the big vats of salted, aging fish were stored, waiting to be strained for its liquid. Huynh, the manager of the section was there, stirring some of the vats with a wooden paddle. “Hello, Chen” he said, wiping sweat from his forehead. Chen smiled at him, grateful for a refuge from what had just occurred, and helped Huynh put out a stack of baskets for straining the fish sauce.

To annoy his parents, Chen often went to the factory just to talk to the workers and eat his lunch with them, oblivious to their awkward and embarrassed looks. Sometimes he would offer to share his lunch with them, but they always declined, politely. They would in turn offer a taste of their lunch to him, but he dreaded it because of the inevitable prahok that would be littered through it. The salty, fermented fish paste was abhorrent to him, it smelt of old encrusted socks, but the workers like most Khmers seemed to put it in all of their food. Nevertheless, when they offered it to him he would always eat it, swallowing with a mouthful of white rice to dilute the taste. He refused his fathers’ insistence to, like his uncle, communicate with clients, or look after the accounting, or negotiate with the fish suppliers, preferring instead to handle the fish stock with the labourers, knowing that it infuriated his father.

Chen’s parents had expectations of him as the eldest son to eventually take over the business. But he had no intention of doing so and took his father’s red-faced silence as a badge of pride, as a sign that he was doing the right thing. Chen’s father’s face became perpetually lined in a grimace, as if the milk he drank everyday had soured. And after the argument they had, Chen’s mother was mute and withdrawn, no longer pushing plates of food towards him at the dinner table.

***

The Mekong river ran through Chen’s town, making it a busy port city with ships flitting in and out like migrating birds, transporting passengers and goods onwards to the capital Phnom Penh. It was a hub for many Chinese businesses, many of whom Chen’s father knew, and many, like Chen’s family on his father’s side, had been there for several generations. They opened up shops that lined the main street, selling everything from groceries to clothing to electrical goods. They also opened up factories like Chen’s father; abattoirs, piggeries, packaging of imported goods. The town was lively with activity during the day but also, especially, at night. The covered central market would turn its lights on, and delectable smells would waft from it as stall owners grilled skewers of meat and deftly fried noodles. They also arranged their sweets for display, sweets like agar jelly and sticky rice and fried banana that would attract both customers and flies. Fat babies would be carted out alongside family members, their faces syrupy with coconut cream. Young men would come out smartly dressed in jeans and pressed coloured shirts, while the young women clutched at handbags and carefully done hair. Chen’s father however did not let his children out during the evening. The people crowding the markets at night, laughing, eating, bargaining over prices, did not hide for Chen’s father the town’s inherent dangers. He often said to his children, “If I catch you going out at night…” leaving the rest of the sentence a silent menace. He would often look at Chen while saying this.

The town had been used to seeing for a few good years now the erratic presence of bodies floating in the river like bits of log wood. Bodies of men that bobbed face up in the downstream would appear like ghostly apparitions, their hair and clothes plastered to their bodies like life-sized painted dolls. This always happened after every bombing near Chen’s town. The grey sleek body of the planes, like a mutation of a giant bird with its sliver belly visible from the ground, terrified everyone when they came flying in, which if low enough, could be seen the words ‘U.S. ARMY’ painted on their tails. They stooped low to release their eggs of a hundred iron bombs, flattening out the land and the people who lived on it for hundreds of metres. The sound of these occasional bombings could be heard from the town even though the targets were the thick jungles bordering Vietnam and Cambodia.

Parts of the jungle became burnt out shells, on both sides. Chen’s father knew that Vietnamese guerilla communists would often run across the border over into the Cambodian side and into Chen’s town after their encampments were attacked, hiding amongst the bustle of the markets and the everyday life that was lived there. Chen’s father also knew that goods arrived at the port not only to be transported onwards to Phnom Penh, but also the other way around. Back towards the jungle and destined for the base camps of the Viet Cong, food and military supplies got transported by the Chinese government. Chen’s father, his friends and business associates did not talk about it, even though Chen’s father knew that some of them were involved in helping the goods to pass through, bribing the local authorities, or lending the use of their trucks.

Chen’s father turned away from it, did not want to be involved but did not want to denounce it either. His mind was occupied with how to make his business grow and make more of a profit then it currently was. He had taken on two new workers with the expectation that more orders were coming from one of his main clients. But the order had not come through, with the usual excuses made by the client, “You know how these things work”. Chen’s father now did not return from the factory until late at night. He would come home to eat his dinner and then go to bed, before leaving again early at dawn the next morning.

One day, Chen’s father unexpectedly came home earlier than usual. He had heard about some unrest in the streets and had let the workers go home early.

The King had been deposed.

This was what Chen’s father found out when he turned on the news on their TV, one of only a handful of TVs in town. The government-sanctioned news kept repeating the same thing on a loop; that a vote had taken place in the National Assembly which had removed King Sihanouk from power. In his place, the General Lon Nol had assumed the role of Head of State on an emergency basis. The news reports did not elaborate on why this had happened, nor how long it was going to continue.

Chen’s mother went next door to ask their neighbour what was going on. “Haven’t you heard?” said Bong, an old woman with hair that had gone completely silvery-white and deep bronzed skin that looked like polished mahogany. She sat cross-legged on her wooden bed. Everyone called her aunty, even though she lived alone and didn’t seem to be anyone’s aunty. “Lon Nol has gone and declared himself President while the King was in Russia”. She clucked a noise of disapproval, her lined eyes squinting, “Ooh, he’s dismantled the Kingdom like a broken-down clock!”.

She continued to chew on some betel nut leaf, fanning herself with a piece of cardboard. “It’s effectively a coup, that’s what everyone is saying.” Bong leaned in closer, showing her stained red teeth, “People are saying the CIA are behind this”, she whispered, “You know who they are, right?”

Although the TV did not give much further news, the radio proved to be more accommodating. Chen’s father found a radio station that was transmitting from Beijing, where King Sihanouk had found exile. He denounced the coup, blasting his message angrily in a broadcast intended for the Cambodians who were able to tune in and hear him. This is only a temporary situation, he said, voice muffled by the inevitably bad connection on the radio. I am setting up a government-in-exile here in China to fight against Lon Nol.” He continued, “I know I have denounced the Cambodian communists before, but this time they will help us.” The radio crackled. “We must all get behind Pol Pot and his party! We must support the Viet Cong and fight the American imperialists!”

Chen’s father temporarily shut down the factory. His mother fervently prayed in front of their small golden statue of the Buddha and offered incense sticks to their ancestors for protection. Chen’s father sat at his desk at home turning the pages of the factory’s accounts book back and forth, the numbers a blur in front of him, lines creasing his forehead.

For Chen, however, it was the call to action he needed. Like a bird who knew instinctively when to migrate, he knew that this was his moment. As Mao wrote, “While no one likes war, we must remain ready to wage just wars against imperialist agitations.” It was not a moment of his own making, any more than finding oneself in the eye of a hurricane is a moment of one’s own making, but nevertheless, he recognised it as a precipitate time where he could decide to act.

Like young birds who wanted to fly too early from their nest, their soft, fledgling wings flapping awkwardly but resolutely, Chen and his friends from the political study group resolved to leave for the jungle to join one of the Viet Cong’s base camps. At this time, many Chinese young people in his town had started to go missing, in twos and threes. When it started occurring, not a word was said about it within the Chinese community but everyone knew- these young people had left home to go into the jungle to join the neighbouring Vietnamese Communists. Chen and his friends wanted to follow in their footsteps, and together they made a plan.

On the assigned day, Chen carefully tied a bundle of clothes into a bag and strapped it across his chest. He considered taking a kitchen knife, and even folded one into his bundle of clothes, but then decided against it. The army would give him any necessary weapons, he thought. He waited for his father to leave for the factory at dawn, which he had started opening again, before quietly slipping out of the house to the sound of pigs squealing. The ones to be sold at the market that day had just been slaughtered.

His family would not find out until it was time for breakfast, when Serey or his mother, calling him to the table, would find his bed empty. However, as he was waiting for Kiet at the market at their rendezvous point, an unfortunate incident occurred. His Uncle Kong saw him from across the street through the gaps between the rush of traffic of motorbikes and cycle rickshaws. He saw Chen with his bundle of clothes and knew immediately. Although Chen was now eighteen, he was no match for his uncle who was tall and big, filling out his frame like a younger version of Chen’s father. Kong crossed the street and grabbing him by the arm, dragged Chen all the way back to his house, red-faced but not saying a word. Chen was too frightened to disobey or to argue. On their arrival, Chen’s mother looked at them and did not even have to ask. She cried hysterically for Serey to run to the factory to inform his father, a fear striking at the frame of her body. When Chen’s father came home, Chen did not say anything but stared at him coldly. Chen’s father did not say anything either, instead he grabbed his walking stick from the umbrella stand and struck Chen with broad, powerful strokes all over his body, yelling at the top of his voice, his face darkening, “So you want to go eh?!” thud, thud, thud. “I’ll show you how to go” thud, thud, only pausing when his wife pulled at his hands, cried at him to stop. Then he commenced again.

Afterwards, Chen laid in his bed rubbing the red splotches on his legs and cursing his father; for hitting him but most of all for not letting him go. He smarted at how unfair it was, to be on the cusp of being part of something so important and extraordinary, where he could finally affect the world in some way, only to be stopped by a father who only knew how to do one thing: make money. His images of fighting and of glory were crushed as he lay prone in his bed and this hurt him more than the growing welts that were forming on his body. He ignored his mother when she entered his room with rice porridge, entreating him to eat something.

But even in his anger, Chen felt confident. He rubbed the large bruise on his arm that had darkened into a deep black- blue. He had just thought of another plan to reach the jungle.

“People of the world, unite and defeat the U.S. aggressors and all their running dogs! People of the world, be courageous, and dare to fight, defy difficulties and advance wave upon wave. Then the whole world will belong to the people. Monsters of all kinds shall be destroyed.”*

*Mao Tse-tung, “Statement Supporting the People of the Congo (L.) Against U.S. Aggression” (November 28, 1964), People of the World, Unite and Defeat the U.S. Aggressors and All Their Lackeys, 2nd ed., p. 14

May 16, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

Lynda Ng was born in Wollongong. She is a graduate of the NIDA Playwrights Studio and the editor of Indigenous Transnationalism: Essays on Carpentaria (Giramondo Press, 2018). Having lived in Hong Kong, Oxford and Berlin, she currently teaches literature at the University of Sydney.

Lynda Ng was born in Wollongong. She is a graduate of the NIDA Playwrights Studio and the editor of Indigenous Transnationalism: Essays on Carpentaria (Giramondo Press, 2018). Having lived in Hong Kong, Oxford and Berlin, she currently teaches literature at the University of Sydney.

Silent Country

When she was a little girl, Melanie’s secret power was being Chinese. She had been gifted with a straight black bob, dimpled smile and big, wide eyes that made her look like a doll. Other children couldn’t help themselves. They would cross the playground just to pick her up and cuddle her. People would stop on the street to exclaim to her mother, “She’s so cute!” and reach down to pat her on the head. The weekly shop was a social activity. Shopkeepers would hand her things – a frankfurter from the butcher, a lolly from the corner shop, a pencil from the newsagent – and laden with gifts, she would return home infused with a sense of contentment and wellness. When she was a little girl, the world was a place that promised benevolence, admiration and love.

As a teenager, Melanie started to look less like a doll and more like a woman, but she learned how to compensate for these changes. She grew her hair long and augmented her brown eyes with dramatic winged tips. Some of her Asian friends complained when people asked, “Where are you from?”, but Melanie always seized the opportunity to embellish. She spun tales for them about her past: she was descended from a ferocious line of Qing dynasty bannermen, or a warlord’s beautiful princess, or a tragic concubine who spent her years in lonely opulence. She gave herself more exotic blood: Mongolian, Hakka, Tibetan, Hui. In this manner, her Chineseness could still be effective. People would exclaim, “How interesting!”, “What an incredible story”, “You’re very beautiful.” This took her all the way through school and university, and still the world promised to be everything she might wish for.

It was only when she ceased being a student and became instead a young woman looking for a husband, or employment, that Melanie realized being Chinese could be a problem. There was the patronising way strangers sometimes spoke to her, in tones that presupposed she would never dare speak back. There were interviews where people commented on how good her English was. And then she went up for promotion and was passed over because ‘she wasn’t assertive enough’. The position went instead to an outsider, a young man who didn’t know her clients as well as she did but who could certainly throw his weight and voice around. As an adult, she discovered that those fairy tales about being an exotic Asian princess were not her dreams alone, but a common fantasy for many of the men who wanted to buy her drinks and work their way into her bed. Their willingness to ignore reality was frustrating, to say the least, and depressing in the event.

But this was not the fault of her Chineseness alone. It was also the general situation of many of her friends, working women who discovered that times had changed but things were not really that different. Men now wanted a partner who was educated and witty, who would bring home a salary to match theirs. But they also wanted this same woman to cook well, keep the house clean, to look after the babies and be able to iron their shirts in the morning. Melanie and her girlfriends commiserated with each other in laneway bars and hipster cafés over the high rents, the double-standards, and the general unwillingness of their dates to commit to someone who might earn more than them. Melanie and her friends had trained to be bankers, lawyers, government policy-makers. They found themselves now, five years down the track, in jobs that required them to work until midnight putting together Powerpoint presentations or assembling documents that few people would actually see. As the years started to add up they mentally adjusted their future families from three children, to two, down to one, and tried their best to keep an encroaching sense of anxiety at bay.

Some of her friends gave up, and moved to New York. In many ways, the dating scene was the same, but there was more work available, more opportunities in banking, and the rents were cheaper. Melanie toyed with the idea. She’d heard that Aussie girls got lots of attention in New York. By crossing the Pacific you became a different sort of exotic creature. In other ways, though, the idea of leaving terrified her. Her mother had always insisted, “We are from here. Your people go way back, back in time in this land.” Buried somewhere amongst the background noise of news and trivia, there were half-remembered anecdotes of Chinese maps showing that they had discovered and charted Australian shores long before the Europeans. Piecemeal memories of a time when China had been curious about the rest of the world, before the Middle Kingdom closed itself off and settled back comfortably into a self-indulgent, self-satisfied stupor.

She told herself she was too Chinese; she wanted to be close to her parents. She lived in a share-flat just a couple of suburbs down the train line from the family home, and returned for family dinner every Sunday without fail. She told herself she was too Australian. She had visited New York a couple of times and liked it, but she couldn’t imagine suffering through the cold there year after year. She couldn’t imagine life without the dry, hot summers, the beach, the gumtrees and the giant ibis rooting through garbage bins at lunchtime.

She listened to friends, and relationship columnists, and tried to be more open-minded as to who she went out with. She installed a dating app on her phone and met men from different parts of Sydney, men from different backgrounds. Two more years went by, and she was passed over for promotion once again, this time because she ‘wasn’t enough of a visionary’. The young man who had taken the Directorship last time was moved across to the bank’s Singapore office. Another young man took his place. This one not as loud as the first, but with the same overbearing confidence and tendency to ask Melanie to fix the lunch order when they had their weekly team meeting. She broke up with her latest boyfriend, who she had been enjoying very much, when he made it clear that he would never consider taking time off work to be a stay-at-home dad. He was an administrator who earned half of what she did and he told her all this while they dined at a fancy restaurant, where she was expected to pick up the bill. She tried to point out that the future, as he envisioned it, was impractical. He disagreed. There was not much left to say after that. New York began to look more promising.

One weekend, feeling fed up and despondent, she raised the possibility with her parents. There was a pause, a staccato beat that threatened to become a legato, finally broken by a gentle cough from Melanie’s father. Silence was a common means of communication in their house. In the spaces between words, no commitments were made but all judgements held. The cough allowed them to progress naturally to safer topics, such as the tenderness of the char siu pork, and who thought the Swans were going to win next weekend. She might almost have doubted that she’d spoken out loud – perhaps she had only uttered those words in her mind, a clear demonstration of the ‘lack of assertiveness’ that was holding her back – except for the mournful look that her father gave her when dinner was over.

He had come to Australia on scholarship, a skinny, nervous-looking nineteen-year-old whose long fringe kept flopping into his eyes. One of nine siblings, it had been a series of firsts for him. First time on a plane. First time in an English-speaking country. First time attending university classes. First time completely on his own.

Melanie’s mother had spied him wandering around the Quad at Sydney Uni, looking lost. When she stopped to ask if she could help, he looked at her with startled eyes and blushed. Her mother knew in that moment that she was going to fall in love with this sweet, gentle soul. To this day, her father maintains that he was simply looking for his classroom when a tiny Chinese girl dwarfed by her backpack emerged from the crowd and said something to him, “in that bloody incomprehensible Aussie accent.” He denies blushing. But he does admit he was rendered speechless.

Not being a man predisposed to retrospection, he hadn’t told Melanie much about those early years. He had a good life in Sydney, and he was quick to point that out. But at night, as he huddled over the phone, she would hear snatches of Cantonese and laughter that belied his homesickness. With three brothers and five sisters, these phone calls came frequently, especially now that they cost next to nothing. And after every conversation, without fail, he would pace the house restlessly.

Unlike others they knew, no one from her father’s family had followed him out to the West. They had come for visits and duly expressed their appreciation for the size of his house, the lawn, the double garage (“so much space, so much space!”), and yet it was clear that none of them really envied him.

He had made a life for himself, that is true, and found himself a beautiful wife. But his wife’s Chinese was heavily accented, nearly incomprehensible. His daughter’s even worse. The houses in Sydney were roomy but the streets were empty. It was a city that sprawled out to nowhere. A nice place to visit on holiday, not necessarily a place where any of them wanted to stay. Back in Hong Kong, in the vertical city of lights and fortune, was where they felt alive. Why would they want to give that up to come here, to simply wait their time out amongst foreigners? And besides, back in Hong Kong they all had each other. Life without family, what sort of life was that?

So he remained, an immigrant amongst other immigrants, a stranger feeling out his way alongside other strangers. He never lost the sing-song of his Chinese accent but over time it came to be overlaid with the broad, growling stretches of an Australian one, a combination that Melanie found at once acutely embarrassing and comforting in its familiarity. As he mangled the English language into new permutations, he tried to come to terms with the fact that he would likely die in this country, far away from where he was born. That he loved his wife and daughter went without saying, but a part of him couldn’t help but feel melancholic at the fact that they would never know him in his native tongue and therefore never know who he really was inside. He was increasingly resigned to being the quiet and dependable man they knew. The witty and animated version of himself had kept up its frantic chatter at the beginning but, with practice, he had learned to quieten it. To send it gently to sleep so that, on most days, it was simply a memory of someone he had once known but could now barely recognise.

As he walked her to the door he said, “It is difficult to start a new home elsewhere. Why leave unless you have to?”

The other indication that her words had been observed, if not remarked upon, came a week later when her mother asked if she would meet her at the Art Gallery. For her mother, who had worked as a dental secretary her whole adult life, one of the greatest possible joys was to sit with a single-serve pot of English Breakfast tea and a scone on the terrace, gazing out towards the water. When Melanie was a child, they had made the journey once a month. Even then, Melanie was able to connect her mother’s tea drinking with her own forms of play-acting. She wasn’t sure if her mother imagined herself as a colonial stateswoman, a lady of leisure, or simply a patron of the arts. But she swirled those dreams around in her teacup, doused them liberally with sugar and milk, and drew comfort from the warmth in her throat as she swallowed them.

Today there was no mention of tea, however. Her mother gripped her arm and steered her expertly through the gallery, past the whimsical watercolours and the bold impasto paintings, towards one of the more sombre rooms at the back. This one contained photographs mounted on vanilla cardboard. The black and white reminders of a colonial settler history.

They did a lap of the room in silence, her mother’s arm wrapped in a companionable way around hers. Melanie was surprised to see that the display hadn’t changed much over the years. There was one photograph in particular, titled ‘Aboriginal Mia Mia’ that she remembered from her childhood. Four Aboriginal figures, three women and a man, positioned next to a small hut made of bark and leaves. Two figures stood, two sat in repose on the grass. They were all dressed in formal Victorian garb: the man with a waistcoat, the women with corseted waists. One woman held a long stick that towered high above her head. Melanie wasn’t sure if it was a spear or another sort of tool, but she liked the way it made the woman seem warrior-like. She was an anomaly amongst photographs of white men with funny Victorian beards and Aboriginal men with painted bodies and elaborate masks. There was a postcard entitled ‘Australian wildflower’ that depicted a bare-breasted Aboriginal woman smiling expectantly from behind a carefully-positioned waratah bush.

“Do you know why I like this room?” her mother asked.

“Because it’s peaceful.”

They circled back to the photograph of four Aboriginal figures. Melanie’s eye returned to the woman who guarded the entrance to the hut with her tall stick, high collared shirt and defiant stare. Melanie knew that, in reality, the photographer must have positioned her there. He would have told all four people where to stand or sit, to hold their poses, and then to wait for at least thirty seconds while the sun imprinted the likeness of their bodies onto his film. He probably made them hold their poses for at least a minute, maybe more, just to be certain that he’d got the shot he wanted. But perhaps once their time was up, once he’d given them permission to move again and was gathering his equipment, that Aboriginal woman had expertly sent the stick sailing through the air, carving an arc that passed just by his cheek and landed over his shoulder. She wouldn’t have struck him, but her point would have been made. The woman’s angry defiance was there in her eyes, still burning over a century later.

Melanie’s mother wasn’t interested in the women, however. She pointed towards the man who stood amongst them, his gaze perpetually fixed on something just beyond the frame.

“I come here because that is your great-grandfather. My grandfather.”

In the silence that followed, even Melanie couldn’t be sure of quite what was being conveyed. She wanted to ask her mother to repeat herself, but that wasn’t their way. She had heard correctly. Her mother smiled, understanding of her confusion.

“It’s a secret. My own mother only told me after I had had you, when I had become a mother myself.”

“But how is it possible? I mean, wouldn’t we know?”

Melanie glanced down at her hands, unconsciously gesturing towards herself.

“Through what? Through skin? Through eyes? From the nose?” her mother was nearly laughing at her.

Melanie stared into her mother’s face. The brown eyes rimmed by severe black glasses, the hair that had long ago turned white but was carefully maintained in Natural Black (Clairol #122), the tan skin that had become freckled over time. Peering into that face, the panic suddenly welled up in her and she wondered if she would ever stand here with a child of her own or if she was destined always to gaze at an older version of herself.

“I was going to wait until you too had become a mother, but as you’re talking about leaving Sydney, I thought it was time. If something happens to me, you might never know. I wanted to stand with you in this spot and show you. We are from here. Your people go way back, back in time in this land. No matter what other people tell you, you will always belong here. Here.”

Together, arms enfolded, they stared at the photograph on the wall. There were many questions but all would be answered in time. There was a genealogy to be reconstructed, a story of how an Aboriginal man found a Chinese wife. Another story of how a Chinese woman with a mixed-race baby found her way back into Chinese society. A history of the Chinese in Australia, whose roots run deeper than anyone knows.

Melanie couldn’t be sure that this story was the right one. Her mother, after all, was a woman who prayed to various Daoist gods as well as in the Methodist church every week. Her mother was the one who insisted that, if you ate the delicate flesh out of a fish’s cheeks then you also had to pick the tougher bits off the bony tail, to ensure that your luck would ‘come back to you’.

There was something irresistible about this story, though. The crisp image of this man before her, the face of an ancestor. Unlike all the warlords or magistrates or sorcerers she had conjured up during her childhood, this was a man of flesh and blood. Someone who had dreamed, loved, walked on the very same ground she did.

She couldn’t be sure that this story was the right one, but when her mother clasped her hands and bowed her head three times to pay her respects, it seemed right to join her.

May 15, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

Luo Lingyuan was born in 1963 and is a German-Chinese writer. After studying Journalism and Computer Science in Shanghai, she has lived in Berlin since 1990 and published works in German and Chinese including four novels, two short story collections and numerous pieces in literary journals. In 2007 her short story collection, Du Fliegst für Meinen Sohn aus dem Fünften Stock [You Fly for My Son from the Fifth Floor,] received an Adelbert-von-Chamisso Advancement Award, a prize awarded to works written in German, dealing with ‘cultural change‘. In 2017 she was Writer in Residence in Erfurt.

Luo Lingyuan was born in 1963 and is a German-Chinese writer. After studying Journalism and Computer Science in Shanghai, she has lived in Berlin since 1990 and published works in German and Chinese including four novels, two short story collections and numerous pieces in literary journals. In 2007 her short story collection, Du Fliegst für Meinen Sohn aus dem Fünften Stock [You Fly for My Son from the Fifth Floor,] received an Adelbert-von-Chamisso Advancement Award, a prize awarded to works written in German, dealing with ‘cultural change‘. In 2017 she was Writer in Residence in Erfurt.

The following interview was carried out in 2016 by Bai Shaojie as part of her Masters degree in German Studies at the Shanghai International Studies University (SISU). The interview was originally conducted in German and the English translation is by Debbie Lim. Thank you to Bai Shaojie , Luo Lingyuan and SISU for permission to publish the interview in Mascara.

Bai: Why did you move to Germany? What led to your decision?

Luo: I have to say it was actually only by coincidence. During my studies at Fudan University I met a German man who was doing a degree in Chinese studies. That changed my life. We were in love and decided to get married after my studies. And so I learnt German, for the sake of love. Actually I was more interested in French literature and had even studied French for half a year. But then then we moved to Germany. When I arrived in Berlin, I could speak only very little German. My husband spoke fluent Chinese and in China we’d only spoken Chinese with each other. After we got married, I wanted to find to work in Berlin but it was very difficult because I hardly spoke German. I worked as a room maid in a hotel and a saleswoman in a department store. At the same time I learnt German. After some time, it became good enough to be able to work as a travel guide.

Bai: When did you begin writing?

Luo: I began writing regularly in German in 2002. The Literarische Kolloquium Berlin became aware of me and supported my work. Before that, I’d published a few articles in China. At first I only wrote short articles and pieces of prose but soon after stories and novels as well. I took a lot of detours and tried out various things until I found my dream job. My first book was published in 2005. But living as an independent writer isn’t easy. I know many German authors who live from hand to mouth and struggle in vain for grants and publishing contracts. Only a rare few can live from writing alone. I have to do all kinds of bread-and-butter jobs too in order to be able to keep writing.

Bai: Why did you choose this career?

Luo: I‘ve enjoyed reading since I was little. I‘ve always admired the famous works of Chinese literature and secretly always wanted to write myself. Even though I studied Computer Sciences at Jiaotong University, I never had much interest in it. I continued because it was ‘sensible‘. After I graduated, I was given a position as lecturer in Computing, which I did for two years. Then I decided to study journalism because I was looking for a bread-and-butter job that could combine with literary writing. I already knew back then that as a writer you always lived on the border of poverty. But it was during this degree that I met my first husband, which completely changed my plans. I learnt a new language and only after 11 years I became a journalist and was able to write articles in German as well as in Chinese.

Bai: Many migrant writers write in Chinese. Why do you write in German?

Luo: Well, Gao Xingjian writes in French, and Ha Jin and many other Chinese authors write in English. Whoever writes in the language of their host country can communicate an image of their home land much more directly. I’ve also read a lot of books in Germany about China. But each time I‘ve felt that the way things were depicted was somehow odd. The China that I knew was different from the China in these books. So I came upon the idea to tell the German people about my country, in their language. I hope that Germans can get to know China and its people better this way.

Bai: How did you choose the subjects for your books?

Luo: That’s difficult to say. I write what I enjoy writing. When I find myself thinking about something repeatedly, when my thoughts keep returning to some person, some story or even some city then I feel that maybe I should write about it. But my subjects often come from my surroundings. People ask me questions about the people in China and I try to give an answer through my books.

Bai: I’ve noticed that you’ve written a lot about China, but not Germany. Why?

Luo: When I came here [to Germany] I was already 26. I spent my childhood and youth in China, and the Chinese culture and my family have influenced me deeply. For a story, you need people – they’re the starting point of every narrative. And for me, it’s easier to understand and create a Chinese person. But it’s only a question of time. Maybe soon I’ll write more about Germany.

Bai: How do you manage the relationship between reality and imagination during the writing process?

Luo: The starting point is always reality and often even a concrete incident. But I look at reality quite critically. I attempt to figure out the core of the characters, based on what they think, say and do. It’s only during this phase that the imaginative power sets in. I ask myself questions: Why did this person do this? What would he or she do in other circumstances?

Bai: You’ve referred to the city of Ningbo in many works. Do you have a particular connection to the city?

Luo: No, Ningbo is a symbol for the rapid economic development in China. The city is much more interested than other cities in colloborating and exchange with foreign countries, but it’s not as well-known overseas as, say, Shanghai. I myself led at least two delegations from Ningbo on tour through Europe and met people from the city. Most Germans know of Shanghai in particular. The city has become almost a cliché and many Germans think that, apart from a few skyscrapers in Pudong, China doesn’t have much to offer. I lived for seven years in Shanghai and was very happy there but I’d like to show my readers that there are other cities in China too. If I ever write about Shanghai, it will be something special.

Bai: You’ve lived in Germany for 26 years. What are your views now towards China and Germany?

Luo: I’m still Chinese inside. That will probably never change. The richness of the Chinese culture with its vibrant traditions and deep thought, its music and reknown literary role models, still has a major influence on me. It’s such a powerful influence and can’t just be cast off. I don’t want to separate myself from it either. On the other hand, I’ve also adopted a lot from the German people, for example, conscientiousness. When I began writing, my husband once asked me how I could have made the same mistake three times. It unsettled me and I realised I hadn’t been very thorough or placed much value on precision. After that it was clear to me that I had to be more meticulous. The Germans are are very conscientious and strive for perfection in everything that they do.

Bai: Which experiences after all these years have remained particularly in your memory? What would be your suggestions for fellow countrymen who plan to come to Germany?