March 20, 2019 / mascara / 0 Comments

David Adès is the author of Mapping the World (Wakefield Press / Friendly Street Poets, 2008), the chapbook Only the Questions Are Eternal (Garron Publishing, 2015) and Afloat in Light (UWA Publishing, 2017).

David Adès is the author of Mapping the World (Wakefield Press / Friendly Street Poets, 2008), the chapbook Only the Questions Are Eternal (Garron Publishing, 2015) and Afloat in Light (UWA Publishing, 2017).

Photograph: Anne Henshaw

Life is Elsewhere

~ Milan Kundera

else the universe removes its cloak of dark matter and reveals

the strings of stars lying behind it

else the universe is not the universe at all but another and another

else the road taken is not one but many

and the road not taken is multiples of many

else life is smoke and mirrors behind which other lives

else wind is a giant hand brushing away

clouds of anger

else love is a prized toy, too easily discarded

else our eyes see and see nothing,

we walk, oblivious, in quicksand

else story is whisper, horizon, clouds piling up and up

else nothing is truth except lies,

told and untold,

where the volcano shifts and rumbles

where the girl hides inside herself,

where the words are spoken into the air

where everything is forsaken for love

where expediency trumps morality,

where politics outweighs compassion

where the wave of indifference is a tsunami

where the damaged and wounded

walk invisibly among us

where everyone speaks and no one is heard

where denial subverts and distorts truth,

where rationalisations deny accountability

where we cannot support the weight of our hypocrisy

where we fail to overcome the litany

of our failures.

March 20, 2019 / mascara / 0 Comments

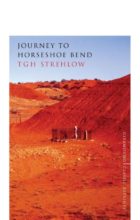

Journey to Horseshoe Bend

Journey to Horseshoe Bend

by T.G.H. Strehlow

ISBN : 978-1-922146-77-9

Giramondo

Reviewed by JAMES PAULL

If not for the Christian gravesite, the book-cover image of Central Australia might appear an all too familiar trope. Industries as much cultural as primary have engaged in modes of wealth extraction from this landscape. In mid-century modernist mythography, for example, the desert spoke of a nation’s spiritual void. By contrast, the grave’s fragile occupancy in this hostile sun-blasted world alludes to a specific historical biography. The telling of its story is no less indicative of land’s meaning, however, no less imbued with mythography.

The biography in question is Carl Strehlow. The Lutheran pastor of Hermannsburg Mission from 1894, Strehlow succumbed to severe illness in 1922. In October that year a party set out to save his life, journeying along the dry bed of the Finke River with the immobilised Strehlow mounted on a chair on the back of a horse-drawn cart. The story of Carl’s agonised last days and death at Horseshoe Bend and a young man’s coming-of-age became in the hands of his son, linguist and anthropologist TGH (Ted) Strehlow, a literary masterwork.

Journey to Horseshoe Bend was first published in 1969. Apart from a 1978 paperback edition, it has been out of print. This Giramondo edition features a new cover photograph, as well as a specially commissioned essay by Dr Philip Jones, curator of Australian Aboriginal Culture at South Australian Museum. It reproduces the original text including the carefully prepared regional map that formed the endpapers of the first edition.

To revisit the book’s epic scope is to be reminded of its blending of closely observed factual detail with the artful. A simple diary-like entry – ‘It was Tuesday, the tenth day of October, 1922’ – sets the stage for the rising eastern sky to reveal calls of birdlife and Aranda (Arrernte) place-names. Meanwhile, the Mission’s Aboriginal congregation awaits with trepidation their ‘ingkata’ (‘chief’). We learn of Carl Strehlow’s long struggle to build a ‘Christian home’ for the Arrernte at Hermannsburg, as well as his now severely weakened condition due to the combination of pleurisy and dropsy. Carl’s questioning of his faith is introduced, as is the gnawing conviction the Church has abandoned him. His bloated pain-wracked body is revealed to all as he emerges with his wife and fourteen-year old son Theo, before being strapped atop a horse-drawn cart to journey south accompanied by his family and Arrernte horseback drivers. So begins his personal Calvary – the poignancy heightened when the Aboriginal congregation offers an impromptu rendition of a Lutheran chorale translated into Arrernte.

TGH Strehlow began writing the book during an illness resulting in hospitalisation. It was also a period of midlife crisis, when he would abandon his wife and children for a much younger woman. Both episodes undoubtedly shadow the book’s central theme, which concerns the reciprocal nature of death and regeneration.

Successive revisions of the first draft saw the manuscript evolve from autobiography to a form in which Indigenous and settler narratives are interwoven. Strehlow was alert to a mid-century poetics that turned to the outback to frame questions of Australian national identity. Voss remains the most celebrated, but others, including the Jindyworobaks with their focus on Aboriginal culture and natural environment, are equally important. The generation of Arrernte artists commonly associated with Albert Namatjira identifies a third stream.

A passing reference to Namatjira in the book’s opening section invokes something of this awareness; more significantly, it demonstrates the memoir’s doubled philosophical design. Journey is testimony to the convergence of differing stories, peoples and cultures and how they are bounded by conditions of circumstance and region. The lives of the Arrernte peoples and the Strehlows converge at Hermannsburg (Ntarea). The most important form of doubling is that of Carl’s death journey with his son’s coming-of-age. This is because Journey, while a work of synthesis, is, first and foremost, a literary Bildung. Crucially, Theo’s development cannot be separated from his father’s decline.

There is another photo of Carl Strehlow’s grave, this one taken in 1936 and featuring the son, now a young man commencing fieldwork in Central Australia. The recently married TGH revisits the site of his father’s death at Horseshoe Bend. The portrait seems to foreshadow the memoir’s design and thematic preoccupations. TGH’s respectful yet solitary stance embodies something of the burden the author carries in this book. His story remembers in detail the harrowing circumstances of Carl’s death. Journey is a work of mourning, but it is also a nuanced psychic account of the son’s displacement of his father.

Strehlow perhaps is not unlike Hamlet, haunted by the Father’s imposing legacy as missionary and pioneering Arrernte scholar. Although not always acknowledged, Carl’s lifework provided his son the main prototype for much of his ethnography. Aranda Traditions (1947), Strehlow’s groundbreaking study of Arrernte male initiation rites, includes remarkably detailed accounts of Dionysian rituals that see ‘excited young men’ frenziedly dance to exhaustion, thereby shattering the symbolic power of their elders. Journey is comparatively muted, yet no less pointed: its narrative simply avoids recording any direct exchange between Theo and his father. Like the tombstone driven into scorched earth, the inscription of the Oedipal complex runs deep in the author’s personality.

*

The landscape of Central Australia is inseparable from regional mythology. In Journey landscape is a patterned composite of stories whose design can be considered omnipresent and omnidirectional. It is also non-entropic. Carl’s death-journey is recorded across the party’s 12-day trek to Horseshoe Bend. On the 13th day, Theo stands alone at his father’s grave on the bank of the Finke River, conscious of death yet alert to the beginning of his new life. The reciprocal relationship of opposites, father and son, entropy and renewal, disappearance and emergence, structure the journey, but it is storytelling and translation that interweave human as well as nonhuman experience.

The year before his death, Carl completed the monumental eight-volume study of the Arrernte and Luritja peoples he had commenced in 1907 (Die Aranda- und Loritja-Stämme in Zentral-Australien). Born at Hermannsburg Mission, Theo’s first languages were German and Arrernte. Conceived at Ntarea, his clan totem marked the place of Twins Dreaming. By the period of his memoir, TGH had long established himself as the foremost living expert of Arrernte linguistics, song-verse and traditions, most notably in Aranda Traditions and Songs of Central Australia (1971). Strehlow’s ability to juxtapose Indigenous myth with the biography of father and son’s biblical exile encodes his intergenerational drama with a richly arcane cross-cultural knowledge.

Carl’s fate unfolds across a hostile environment marked by heat, drought and fire. For example, three Finke River stations in Central Australia (Henbury, Idracowra and Horseshoe Bend) mark where the travellers rest. For the white bushfolk, Henbury offers a rare permanent waterhole, but for the Arrernte the waterhole of Tunga is the last resting place of Tjonba: ‘giant goanna ancestor’, who in seeking to escape an ancestral hunter burrowed deep into the ground. Idracowra is a corruption of Itirkawara, Arrernte name for Chambers Pillar. The sandstone pillar-like formation locates the final resting place of the mythical gecko ancestor, whose territorial conflicts and ‘abhorred incestuous’ acts were punished by edict from his own ‘gecko kinsfolk’. Synonymous with brutal heatwaves, Horseshoe Bend is Par’ Itirka – its surrounds disclose a series of ‘heat-creating totemic’ centres, the most potent of which is Mbalka, ‘home of a malicious crow ancestor’ responsible for lighting bushfires ‘whenever he flew down from the sky’.

The story of Irbmangkara waterhole, with its network of totemic centres linking bloodthirsty myths of warring clans, overlap with living testimony as to the deeds of police trooper W.H. Willshire, whose murders of the Arrernte led to his arrest in 1891. Willshire’s frontier atrocities loom large in Strehlow’s account representing what might be taken as a literal dialect of colonisation. In describing one of his attacks, Journey records how Willshire spoke of his ‘Martini-Henry carbines… talking English’. Heir to the Lutheran tradition in which language contains the spirit of a people, this comment shrewdly exposes the inherently suspect nature underpinning the settler community’s legal and more broadly cultural claims to country.

Landscape is a palimpsest: multilayered stories from the past seep into the stratigraphy of present-day routes. Frontier atrocities map one surface. Another is the rural community of ‘bushfolk’ described with affection by Strehlow. This in part stems from their respect for Carl, as shown both in their willingness to help him make his way down the Finke and the burial service, where the pastor’s bloated dead body is awkwardly stuffed into a makeshift coffin made of discarded whisky cases (its unopened bottles have been distributed among the bushfolk as a farewell gift from Carl). Grimly touching, the episode offers an ingenious ethno-poetic record of frontier exchange systems.

*

The archetype of the rural folk sharply contrasts with the remoteness of the Lutheran establishment, which Strehlow believed had abandoned his father. Strehlow’s treatment of his father’s anguish draws directly on Christ’s experience of abandonment in the garden of Gethsemane. If the depiction of the bushfolk has dated, Carl’s torments remain harrowing and help explain the lonely, dogged personality of the author, witness to tragic events over which he has no control.

TGH emerges in his own pages as the most complex of outsiders. Whether privy to settler tributes made to his deceased father, or recipient of Arrernte statements that his ancestral home now belongs at Ntarea, Strehlow finds himself alone, saddled with twin heritages. In life, he lived and worked between two worlds: a German migrant in Anglo-Celtic Australia, Arrernte-born but Lutheran-educated, a foremost authority of Central Australian ritual, sacred belief and song, whose work was deeply interwoven with his father’s less accessible, yet equally imposing, legacy. Cast in the third person, ‘Theo’ is just as doubled: a young man transitioning to adulthood but perceived through the eyes of ‘Ted’, his much older self.

The author of Journey was also a man increasingly burdened by responsibilities brought with years of fieldwork. The collecting of custodial objects, stories and song, while not directly evident in his memoir, can be felt. When Journey was published, Songs of Central Australia still awaited publication, despite being completed over a decade earlier. The reasons for delay of his magnum opus are complex – in part related to the costly venture of the book’s design, in part related to sensitivities making sacred knowledge public. In Songs Strehlow describes himself as the ‘last of the Aranda’, expressing what he believed was his custodial kinship with the Arrernte, as well as his lonely standing as the sole surviving custodian of sacred clan knowledge. The sentiment also pervades the memoir of his journey from childhood to manhood, an era he described as ‘passed on as though it had never been’.

If nostalgia is important to the book’s design, it also helps identify the ideological constraints that mark its account of the Arrernte. Described as ‘dark folk’, their presence is finally a cultural backdrop to the main drama. While sparingly used, the phrase reveals a consistent assimilationist purpose, whereby the ‘primitive’ is incorporated into the narrative of Western progressivism.

Strehlow’s assimilationist beliefs would become more pronounced in the years that followed the publication of Journey. In an emergent era of Indigenous land rights and repatriation of sacred objects, he upheld in increasingly strident terms the view of a dying culture to claim sole ownership over the ritual objects entrusted to him by Indigenous elders during his long years of fieldwork. He died in 1978, mired in controversies his convictions had helped generate.

*

TGH Strehlow remains the most ambivalent of Australian literary figures, a pioneering writer-translator of Arrernte verse and performance committed to practices of white ownership and accumulation. Perhaps he is best approached as an outsider of the Arrernte, but a uniquely privileged one. He was conceived at Ntarea, the place of Twins Dreaming, and so was instinctively alert to the coexistence of opposites. His account of the journey reflects this knowledge, unfolding through the eternal interplay of doubles – reverie in the coolness of night, unending torment in the searing heat of day. This imaginative process contributes to the transitional yet transformative poetics of Journey. To speak of death as finality makes no sense in such a world. Just as Carl’s final resting place gives way to Theo’s grasp of the ‘certainty of life’, stasis signifies a circulatory force whose constitutive nature binds all things.

Such a poetics remains significant in today’s politics, but its authority is far more contradictory, flawed and diminished than its author likely intended. Strehlow’s quasi-Wagnerian conviction that myth is a contemporary mode of thinking deepened white understanding of traditional Indigenous culture, while simultaneously repressing its living modern reality. In place of contemporary Arrernte elders, he dramatised his own becoming and positioned this drama within what he believed a greater national culture. In doing so his epic narrative reveals something more than generational bias; it shows settler writing as inseparable from Western colonialism’s historical violence and claims to cultural superiority.

Dr JAMES PAULL is a curator, teacher, librarian, freelance writer and researcher.

March 19, 2019 / mascara / 0 Comments

The Measure of Skin

The Measure of Skin

by Ramon Loyola

Vagabond Press

ISBN 978-1-925735-14-7

Reviewed by FELICITY PLUNKETT

Poets have recurrent signatures – words, images, modes and motifs – imprints unique as a fingerprint’s whorl. For Philippines-born poet, editor, lawyer and writer of short fiction, Ramon Loyola, one of these is just this: images of skin, literal and figurative, and an exploration of the ways skin communicates and mediates unique histories.

Throughout his work – three poetry collections, an experimental prose-poetry memoir The Heaving Pavement and a series of comic zines Barney Barnes and Friends – embodiment, skin and porousness recur as images conveying ideas of vulnerability, injury and tenderness.

The Measure of Skin is one of ten titles in Vagabond Press’ vivid deciBels 3 suite, meticulously edited by Michelle Cahill, co-edited with Dimitra Harvey. It sits alongside work by, among others, Pakistan-born Misbah, a visionary weaver of lyric prose-poetry slivers, versions of which were previously short-listed for the Arts Queensland Thomas Shapcott Poetry Prize; Anna Jacobson, winner of that same prize in 2018, whose debut collection Amnesia Findings (forthcoming, UQP) charts the loss and repair of memory through exquisite poems exploring trauma and resilience, Jewish diaspora, injury and healing; and Jessie Tu, one of whose poems was short-listed in Australian Book Review’s 2017 Peter Porter Poetry Prize. deciBels series 3 is gloriously expansive, highlighting a divergent array of poetics.

The poems in Loyola’s The Measure of Skin return to the skin of the speaker’s own body, and that of his lovers, who, bound in the skin of their own stories, have ‘revelled in my skin’. There is skin ‘bound to be touched’, scented with ‘jasmine hint’; the crease of articulate scars, patterned with hair and bruises or more figuratively – ‘parched skin quenched/ Of the thirst for clear answers’ by the wash of seawater. Loyola’s poetry includes all the senses. There are almost palpable textures of ‘glistened skin’, ‘rough… stamens in the rain’ and skin lit and warmed by rays of sunshine. And there is the hue of skin, a question crucial to this collection’s consideration of identity, loss, displacement and connection.

Skin – the soft tissue that covers us – is a layered, hard-working organ that holds us together and provides insulation and protection from pathogens. Its pores do the work of letting in and letting out. It may be a site of injury or healing, associated with bonding, lovemaking and bliss as well as with violence and wounding.

Language is a skin, writes Roland Barthes in A Lover’s Discourse. Words are the surface of layered lexical histories. To peel back layers of the word skin we find the Old Norse skinn – animal hide – itself traceable back to the Proto-Germanic skinth from which come words in various languages meaning to peel back, flay, cut; the scales of a fish or a tree’s bark. There are Latin seeds and Sanskrit ones.

The original syllable, then, moves through languages, layered and displaced. It has left its home to become important in another place. It leaves its flakes in languages across the world.

Just as a word does, so do human beings. In ‘For the Sleepwalkers’, Edward Hirsch imagines sleepwalkers – a metaphor for any of us wandering through this world – as exemplars of what it is to trust and risk, moving through ‘the skin of another life’ in their sleep:

We have to learn to trust our hearts like that.

We have to learn the desperate faith of sleep-

walkers who rise out of their calm beds

and walk through the skin of another life.

We have to drink the stupefying cup of darkness

and wake up to ourselves, nourished and surprised.

When Barthes writes that language is a skin, his context is the citational poetics of A Lover’s Discourse, a book he prefaces with a description of offering the reader: ‘a discursive site: the site of someone speaking within himself, amorously, confronting the other (the loved object), who does not speak.’

The terrain of Loyola’s poems of skin and skinlessness is similar. In an interview with Tony Messenger, he writes about an instigating self-scrutiny as the basis for exploring layers of self and other – ‘to know myself down to the bone in order to confront the many possibilities – delicious and sordid – inherent in the realms outside my own skin.’

Often, these poems contain a ‘you’ towards whom their open, often amorous words are directed. There are quiet poems of pillow-talk, intimate words the reader is positioned to overhear. The book’s first line ‘your hands feel familiar’ reaches towards a sense of the familiar; the affinity that causes the speaker to wonder – and wander – through a dance of possibilities, expressed as neat rhyming paths in the final stanza: ‘go away’, ‘want to say’ and going ‘astray’ are poised as the lover’s options.

Rhyme measures the options, as Loyola’s poems place skin and metrics side-by-side. This weighing-up that shapes the first poem, ‘Familiar’, sets the tone. Putting skin together with measure is a poetic experiment – a kind of scientific and emotional assay – as the poems assess losses and gain, connection and loss, and the ways the body holds memories of trauma and joy. So when a lover’s hands here feel ‘familiar’, the speaker’s plan – (‘i only meant to say hello/ to wish you well on your way but) – tips into indecision, the ‘What is to be done?’ that prefaces Barthes’ book – ‘I bind myself in calculations’.

Among these calculations, Loyola’s poems measure alternatives. In ‘Monkey Suit’, he imagines his lover’s body in the frank unabashed images these poems revel in: ‘His sex is big. His sex is the bomb.’ Part of this is its whiteness: ‘There is never anything whiter… than the shape of his shiny white buttocks’. On the other hand, the speaker’s -assessment is at best self-ironising, at other times directly abject and self-flagellating. This is often a refreshing riposte to a culture commodifying beauty, and at times an unabashed lament. It also suggests a weighing-up of negative and even racist assessments of his own body. He imagines his own sex as ‘coarse’, ‘crooked’ and ‘foul’, yet this is weighed against the pleasure and consolation of connection. The poem’s last stanza ends with a kind of volta, a ‘but’, and a reparative image of afterglow: ‘the same sweetness of souls’, which suggests a rejection of superficial, cruel assessments.

Loyola mediates the measuring of beauty and bodies, balancing perfection and imperfections through discourses of skin binding mind and body. As metaphor does its traversing of bridges, so do Loyola’s speakers and lovers, over empathy’s crossings. This is suggested in the poems’ mode of invocation, invitation: ardent reachings-out, or dialogic inner reflections. Love might be, as Loyola writes in ‘In All the Broken Places’ ‘[u]nbridled, perilous or kind’, but whatever its composition, it ‘steeps the heart and mind’. ‘Touch me’, he writes in ‘Touch Me Where It Hurts’, where ‘my heart sits quietly’; in the place of a wound that ‘does not hurt’.

Loyola’s poems meld a lawyer’s weighing-up with a poetics of skin and vulnerability, where the poems’ speakers wander as outsiders, looking in, or looking into themselves. The poem are shaped along these axes, with balance and symmetry at the levels of structure and the patterning of images, and an imagistic wildness and tonal intimacy in their expression of homoeroticism.

I last saw Loyola at a poetry reading in May. The alignment of our interests had nurtured a gentle online friendship, and we clasped hands with a sense of the weight of that bridge. This was the way of Loyola’s presence in the poetry community. He was a passionate reader of others’ work, a modest promoter of his own, and his interactions had a steady radiance and kindness to them.

In September, Ramon Loyola died suddenly following after suffering a brain aneurysm. The shock and pain of this for his family and loved ones is inestimable, and the loss to the community of poets he nurtured and contributed to with such exemplary generosity is deep.

Writing about Loyola’s poetry of intimate address and mapping this onto the similarly ruminative slivers that make up Barthes’ A Lover’s Discourse, I think of the loneliness each writer evokes, as part of our experience of love. In ‘No Answer’ Barthes writes:

Like a bad concert hall, affective space contains dead spots where the sound fails to circulate. – The perfect interlocutor, the friend, is he not the one who constructs around you the greatest possible resonance? Cannot friendship be defined as a space with total sonority?

In reading The Measure of Skin — first when it was published, now in Loyola’s absence, his poems have a consolatory continuance. Reading his work continues to make us interlocutors in the vibrant spaces his poetry creates.

Notes

- Roland Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments, trans. Richard Howard (London: Penguin, 1977), p. 3.

- Barthes, p. 63.

- Interview, Tony Messenger interviews Ramon Loyola, Messenger’s Booker (and more): https://messybooker.wordpress.com/2018/06/18/the-measure-of-kin-ramon-loyola-plus-bonus-poet-interview/, np.

FELICITY PLUNKETT’S Vanishing Point (UQP, 2009) won the Arts Queensland Thomas Shapcott Prize and was short-listed for several other awards. Seastrands (2011) was published in Vagabond Press’ Rare Objects series. She edited Thirty Australian Poets (UQP, 2011). A Kinder Sea is forthcoming early in 2020.

March 9, 2019 / mascara / 0 Comments

Poetry

Winner: Blakwork by Alison Whittaker (Magabala Press)

Blakwork is radical in its forms and addresses; seeking, unapologetically to unsettle white heteronormative spaces. The poet is also tasked to decolonise discourses in language, law, and popular culture. Whittaker explodes the stock images and racist, reductive tropes that are the foundations of settler nation. With syntactic and rhetorical shifts and with neologisms, her sound poems invigorate the lyric with freshness, vitality and impressive virtuosity.

Shortlisted

Subtraction by Fiona Hile (Vagabond)

A Trillion Tiny Awakenings, by Candy Royalle (UWAP)

The Alarming Conservatory by Corey Wakeling, (Giramondo)

Fiction

Winner: The Bed-Making Competition by Anna Jackson (Seizure)

The Bed-Making Competition is startling, humorous and compassionate in voice and tone. Reminiscent of J.D Salinger’s Franny and Zooey, it offers the wisdom of near-lived experience through the alternating fictional voices of two sisters over twenty years, and their often self-detached, self-performative subjectivities. Temporal partitions bring the past and present into synchrony. The structure of this novella is exemplary; it may be read as short stories, symmetrically arranged, each with a ‘bed-making’ metaphoric trope or juxtaposed psychologically so that destiny is mirrored and reversed. Deep emotional insights are presented through irony and tact gliding over the surface of volatility, confusion and disorder in the lives of Hillary and Bridgid.

Shortlisted

Melodrome by Marcelo Cohen translated by Chris Andrews (Giramondo)

horse by Ania Walwicz (UWAP)

All My Goodbyes by Mariana Dimopolus translated by Alice Whitmore (Giramondo)

Non-Fiction

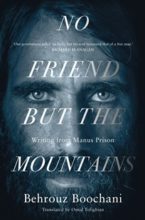

Winner: No Friend But the Mountains by Behrouz Boochani, translated by Omid Tofighian

Winner: No Friend But the Mountains by Behrouz Boochani, translated by Omid Tofighian

(Picador)

As a writer and political thinker Behrouz Boochani is one of the most important figures of our time. In No Friend But the Mountain he achieves the impossible, a treatise of dignity, equality and freedom in the face of a brutal and inhumane imprisonment. Part lyric-memoir, part existential philosophy, meticulously written on a mobile phone and translated from Farsi, this book is an act of interceptionality, re-claiming subjectivity for the subaltern voice of detainees, mediating the political narratives used by mainstream media in profiling asylum seekers. Translated by Omid Tofighian, Boochani follows in a tradition of Antonio Gramsci’s Prison Notes and Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovitch. We are proud that Mascara Literary Review was one of the first journals to publish Boochani’s prose from Manus Island Detention Centre in 2015 (edited by Janet Galbraith).

Shortlisted

The Tastes and Politics of Inter-cultural Food in Australia by Sukhmani Khorana (Roman and Littlefield)

Visualising Human Rights by Jane Lydon (UWAP)

The World Was Whole by Fiona Wright (Giramondo)

Best Anthology

Of Indian Origin Ed Paul Sharrad and Meeta Chaterjee (Orient Black Swan)

A ground-breaking collection of writing by Australian Indians, edited by Paul Sharrad and Meeta Chatterjee Padmanabhan. It gives readers access to lesser-known material from published writers like Meena Abdullah, Suneeta Peres da Costa, Sudesh Mishra, Michelle Cahill, Christopher Raja, Sunil Badami, and Christopher Cyrill. It also introduces writers such as Manisha Anjali, Aashish Kaul, Rashmi Patel and Sumedha Iyer. Resisting homogenised or hierarchical representations of the Indian-Australian community, contributors spread not only from Kashmir to Tamil Nadu, but also include Anglo-Indian voices and work from the Fijian and African Indian diaspora now living in Australia. The introduction outlines the discriminatory legal and political cultural framework which Australian Indians have had to navigate historically. Indians are the second largest group of immigrants in Australia; even still the editors, both postcolonial scholars, could not interest an Australian publisher. While there have been Asian Australian anthologies such as Wind Chimes and Contemporary Asian Australian Poetry, and sparks of interest through conferences and academic writing; the focus is often on China or Southeast Asian Australian writing. This collection locates the Indian Australian experience of South Asia with all its richness and flourishes firmly in the canon.

Shortlisted

The Big Black Thing: Chapter. 2 Sweatshop, ed Michael Mohammed Ahmad, Winnie Dunn, Ellen van Neerven

Going Postal: More than ‘Yes’ or ‘No’, Ed Quinn Eades & Son Vivienne (Brow Books)

Light Borrowers, UTS Anthology Intro by Isabelle Li (Seizure)

March 4, 2019 / mascara / 0 Comments

Emily Sun is from Western Australia and has been published in various journals and anthologies including Westerly, Island, Hecate, Australian Poetry Journal, and Growing up Asian in Australia. She is currently working on her first novel Maybe it’s Wanchai? and can be found at http://iamemilysun.com

Emily Sun is from Western Australia and has been published in various journals and anthologies including Westerly, Island, Hecate, Australian Poetry Journal, and Growing up Asian in Australia. She is currently working on her first novel Maybe it’s Wanchai? and can be found at http://iamemilysun.com

Maybe It’s Wanchai [灣仔]?

Tape deck, SONY

made in Japan

too many places and too many dark spaces

soft wave radio

white noise comforts in mah-jeh’s refuge

masking the sounds of a forgotten city

Non-recyclable plastic and metal, magnetic tape

Tony Leung pre-lust but with caution

together we unspool the tangles and with an

octagonal pencil, made in the people’s republic,

rewind

re-spool

until the music plays

the Banana Boat song

tonic to sub-dominant fragment

then I started a joke

Too many men in skinny flared jeans

No one was laughing.

*

Dying

All animals know they are born to die, but none really believe it.

A mouse caught by a well-fed cat does not know its death is imminent even when that cat presents it to her musophobic owner who will scream, grab the injured mouse up by its tail and feed it to Susa, an Appleyard rescued duck. Susa will pick up the mouse and shake it so violently that its little neck breaks. This mouse will never know that after it disintegrates in the darkness of Susa’s stomach, it will become part of the manure that nourishes the garden it once called home.

Susa was meant to die before the mouse. The council ordered the slaughter of all abandoned domestic ducks found wandering in public parks because introduced species destroy the delicate eco-system. Susa is only alive because when her would be executioner, a middle-aged council worker who was usually on the pot-hole team, looked into Susa’s woeful and purulent eyes, he knew he had no option but to take her to the vet.

This is how it is and how it should be.

*

Only purebreds and country women’s baked goods are assigned prestigious categories at the show. The decorative —animate and inanimate, edible and inedible— are placed in metallic cages or glass cabinets. A purebred Hereford steer or heifer can fetch thousands at a charity auction, but lesser breeds are sold in bulk and that exchange is used to teach business students the concept of futures. There is no gender pay gap amongst these purebreds because both the steer and heifer’s carcasses are as tender as the other after twenty-eight days on a hook. Even the most discerning diner will not be able to tell whether their rib-eye steak was once male or female, only that it was expensive and more so when drizzled in truffle oil.

Piglets are, arguably, not decorative, yet everyone laughs and applauds when they are forced by the farmer/clown to dive into shallow pools of water from two or three metres. Some piglets fear the height and others fear the water. The farmer/clown will not kill them until they break a leg, drown, or grow too large for the plastic pool. They are not sucklings so are safe from Chinese fathers who want to present them, roasted, as a symbol of their daughter’s virginity at her wedding banquet. These diving pigs are kept away from piggeries that house pork because most mammals can sense and taste like fear. A pig on a spit at Oktoberfest is always sweeter when its day begins like any other, rutting and running around, and only dies when, from a distance, Uncle Giovanni shoots it in the head with his a single 150-grain projectile, the unregistered rifle. Uncle Giovanni’s pigs always requires less salting.

*

Simplicity Chan was like any other hopeful animal when she woke up on a wintry morning in the early 21st Century. She went for a swim in the heated indoor pool, ate lunch at Subway, and sat down to watch the Masterchef semi-finals in the evening. By midnight, she was hooked up to an oxygen tank and told by the ED doctor that if she were his sister, he would say “Yes. You have cancer.”

It turned out that Simplicity did not have a procrastinating cancer, one of the types that give you enough months or even years, to tidy up your affairs and perhaps even allow for the medical researchers to develop a new cure. Simplicity had an aggressive but good cancer, and the type that Laura, her assigned cancer support buddy, said she would pick if she had to choose from the hundreds in the cancer catalogue. Laura explained that although the sub-type was rare, it was known to have at least an eighty plus, or so, percent survival rate. The cancer cells were dumb and easily killed by chemo. Only a very small percentage, oh two or was it twenty percent, did not respond to treatment. Laura assured Simplicity that by next Christmas the entire experience would be simply a ‘blip on the radar’.

Simplicity survived so she forgot about dying and started a music studio in her living room. She taught small children how to play whatever instrument their parents wanted them to play, usually the keyboard. It was a shock when, on Valentine’s Day two years later, Simplicity woke up, made dinner reservations at a Gold Plate award winning restaurant but passed out on the hot pavement outside the restaurant while waiting for her date. By midnight she was hooked up to an oxygen tank in a different ED —not the one where she had once spent the night in a dark room hooked up to an IV pole attached to an immobile trolley bed and her head next to a full commode.

This second time around, Simplicity didn’t want a support buddy but she overheard a patient on the ward ask for a priest so she requested a Buddhist monk or nun. She wasn’t really religious but one of her grandmothers had been a devout Buddhist. The young ward receptionist who was in charge of Simplicity’s request said that he could call someone from their list of spiritual counsellors or if she wanted him to, ask a nun who was a regular at the markets where he busked on weekends. He was pretty sure she was a nun for she had a shaved head and walked around in robes that looked a lot like the Dalai Lama’s. She wasn’t on the official hospital list nor was she Asian but she was “really awesome” and always dropped ten dollars into his guitar case whenever he played Blur so she would have been youngish in the 1990s. Simplicity said she didn’t care who it was as long as the person believed in an afterlife because this time no one was saying hers was a good cancer.

The Blur loving nun was dressed in orange and yellow robes when she visited Simplicity on the ward. She said she wore different coloured robes each week because couldn’t fully commit to the temple she’d trained because not all the monks and nuns there were vegetarians. When Simplicity asked the nun why some people were struck down by cancers, the nun also said that all cancer patients were flawed humans in their previous lives and Simplicity’s relapse was evidence of this. But as the doctors still called it a ‘curable cancer’, Simplicity’s sins were relatively minor. Only terminal cancer patients who experienced agonising pain before they were taken to the hot or cold Narakas were the ones who had been murderers and child rapists last time around. Sure, it wasn’t fair for the people they were now but this is just how it was and how it should be. Besides, everyone had more chances since their damnation was time limited in the Buddhist realm and most people would be reborn human.

Simplicity survived again but afterwards stopped visiting the temple where her grandma’s ashes were kept for fear of bumping into the nun. When Simplicity returned home, she was more like the pig whose carcass will still tasted like fear even after drowning in a cauldron of soy sauce and five-spices. Simplicity was unable to make any plans beyond the moment, but soon these moments turned into seconds, the seconds turned into minutes, the minutes turned into hours and the hours into days, so she decided to read War and Peace in the order Tolstoy had intended. But before Prince Andrei left for war for the first time, it happened again. Simplicity woke up one day and by evening she was back on the cancer ward.

The doctor on duty walked in, her eyes blood shot, and told Simplicity that her only cure now was a bone marrow transplant, or they called a stem-cell transplant. The less arduous process, and softer sounding term, meant that more people were more willing to register as donors, this included religious people, except those from specific sects, once they understood that the process did not involve unwanted IVF embryos. The chances of finding a donor were not high, the doctor said, but not entirely impossible. What she neglected to say then was that Simplicity’s odds of finding a match were lower because she wasn’t European, or more specifically Northern European.

*

In year five, Simplicity’s sometimes-friend Nita had asked her, ‘Don’t you wish you had been born something else?’ This was after Shelby started making fun of Simplicity for having ‘slitty eyes’. That was the year when everyone was cruel to each other. Some kid called the teacher a fat cunt so the teacher dragged another kid across the desk and slammed him against the wall. When Nita, more an ally than a friend, and Belinda, the girl with no allies, were absent, Simplicity was teased for looking Chinese or Japanese, and speaking English too ‘posh’. Simplicity later discovered that her accent was one that some English celebrities often adopted to mask their aristocratic upbringing. By that time though, Simplicity had lost the accent and sounded more like Bob Hawke and no longer said daahhnce or Fraahhnce when she referred to the school social or the country across the English Channel. Other than dickhead Don, who pinched Simplicity whenever he had a chance, no one really physically hurt her. Nita though was constantly subject to electric shocks administered by Shelby, who excelled at nothing else. Shelby couldn’t have bullied Nita for looking or sounding different because although Nita was part-Maori, she had blonde hair and blue eyes, and no one made her say ‘fish and chips’ or ‘six’ repeatedly as they did with that other kid from New Zealand. Initially, Shelby used her index finger to shock Nita but then she learnt how to charge up a drawing pin to stick into Nita. If their teacher had seen Shelby’s experiments as a teaching moment perhaps Shelby would’ve ended up at the CSIRO and not an inmate at Bandyup.

At least Simplicity and Nita had each other. Belinda had no one.

At best people ignored Belinda. Most of the others made fun of her for having nits even though she didn’t have any and laughed at her for wetting her pants after someone tipped their left-over lemon cordial onto her chair. They called her all sorts of names and when she got pregnant, in the summer between primary and high school, everyone said that the only way that could have happened was if the guy had put a plastic bag over her head when they were doing it.

Simplicity was glad she wasn’t Belinda or anyone else from her primary school. Of course, she sometimes wanted to be other people, but not any specific person or someone she knew in real life. She wanted to be one of the Bradies on The Brady Bunch but never part of the Keatons from Family Ties. In high school she wanted to be womanlier, like the popular girls. Although her nipples budded around the same time as the other girls she didn’t need to wear a training-bra so she never drew the attention of the boys who went around snapping bra straps. If there were times she’d wished she’d been born something else, she’d long forgotten these moments and it was only now that as the doctor explained to her the limited options that Simplicity’s answer to Nita’s question from decades ago was now yes.

Yes. Simplicity wished she had been born European and more specifically Dutch. Even before this relapse, she’d read about how the Dutch and Germans, the Teutons, had an easier time finding donor matches because of less genetic diversity and higher donor rates. The 19th Century pseudo-science of eugenics benefitted those descended from European colonisers because although their ancestors colonised other people’s lands, intermarriages were rare until long after they lost their colonies. Who would have thought parochialism, apartheid and inbreeding had its merits?

The doctor kept talking but Simplicity wasn’t listening because she was too busy scouring the archives in her mind for examples of people who had low odds but did not die. There was an Ivy-league educated Indian-American guy who recruited everyone from his fraternity and then almost everyone from his ancestral village onto the American stem cell registry. Then there was a Lebanese-Australian who went to Lebanon and founded a cord blood match. She even met the Lebanese president. Simplicity’s placenta and her baby’s umbilical cord were left in the freezer of the hospital where she’d given birth. In this moment she felt rather stupid that she didn’t donate or bank it but instead had the idea to plant it in her backyard upon a doula friend’s suggestion.

Simplicity’s grandmother once said that people in her village used to eat the afterbirth, but Simplicity couldn’t recall which village it was or even in which country, nor how long ago that had been. Even if she found that village, there were still those villages of her other grandparents to find. Hers was a fractured tribe. She often joked about how relatives are meant to dislike each other because it reduced the chance of inbreeding. Secretly though, she envied friends who enjoyed weekly Joy Luck Club style extended family gatherings where there were enough people to warrant the purchase of an extendable dining table. A friend who came from such a family said that these gatherings were overrated and a drag but conceded that’s why her family didn’t die in the Vietnam war.

Simplicity was dying … again.

Like the other two times, death was swelling up inside her, compressing her nerves and crowding out her vital organs. This time, however, she could not laugh at her reflection in the mirror or make YouTube videos wearing a funny wig as she had the previous times. This time she needed out where she was really from, and hope that when she found her tribe, they would care about whether she lived or died.

‘It’s a lot to take in,’ the doctor said gently. ‘I’ll see you tomorrow. You should try to get some rest and eat a little something before bed.’

The doctor disinfected her hands and left the room.

Fear smelt like pink liquid hand sanitiser.

*

February 23, 2019 / mascara / 0 Comments

Jonno Revanche is an interdisciplinary writer currently based in Sydney on Gadigal land.

Living vicariously through you

Everything taken from

Us while stillbirthed as

Illegible girls, we’ve

Got to make up for now as lost

time, really grown, life-size people –

Full and tenderoni, looking over

Our shoulders, at prism flashes

Left behind. Aggrieved parents

Not unlike ghosts fogging around

Us, trying to ring out older names

At some point, conveniently forgetting

– Blank wages are ours to own now.

I’m over this scrimmage, this

Ghostly tenure – all I long to

See is Arcadia, in the arms of a sister.

Our heaviness either goes

Unseen,

recognised as unsalvageable –

Bodies all too burdened for

this Modern place

No, we won’t be blacked out;

It’s

Untenable to some, but

Grab your sheetmusic: I hear the sound of

Lush Square Enix RPG type fields and songs, a

Distant beyond vision –

And, honestly?

we’ve got

it all

covered

February 20, 2019 / mascara / 0 Comments

Richard James Allen is an Australian born poet whose writing has appeared widely in journals, anthologies, and online over many years. His latest volume of poetry, The short story of you and I, is published by UWA Publishing (uwap.com.au). Previous critically acclaimed books of poetry, fiction and performance texts include Fixing the Broken Nightingale (Flying Island Books), The Kamikaze Mind (Brandl & Schlesinger) and Thursday’s Fictions (Five Islands Press), shortlisted for the Kenneth Slessor Prize for Poetry. Former Artistic Director of the Poets Union Inc., and director of the inaugural Australian Poetry Festival, Richard also co-edited the landmark anthology, Performing the Unnameable: An Anthology of Australian Performance Texts (Currency Press/RealTime). Richard is well known for his innovative adaptations and interactions of poetry and other media, including collaborations with artists in dance, film, theatre, music and a range of new media platforms.

Richard James Allen is an Australian born poet whose writing has appeared widely in journals, anthologies, and online over many years. His latest volume of poetry, The short story of you and I, is published by UWA Publishing (uwap.com.au). Previous critically acclaimed books of poetry, fiction and performance texts include Fixing the Broken Nightingale (Flying Island Books), The Kamikaze Mind (Brandl & Schlesinger) and Thursday’s Fictions (Five Islands Press), shortlisted for the Kenneth Slessor Prize for Poetry. Former Artistic Director of the Poets Union Inc., and director of the inaugural Australian Poetry Festival, Richard also co-edited the landmark anthology, Performing the Unnameable: An Anthology of Australian Performance Texts (Currency Press/RealTime). Richard is well known for his innovative adaptations and interactions of poetry and other media, including collaborations with artists in dance, film, theatre, music and a range of new media platforms.

In the 24-hour glow

It is less than 24 hours

since we first made love.

Every moment fading in slow motion,

like a sunset, watched from

a public housing park bench,

24 years from now.

People are flawed stories

that unfurl as perfect wisdoms.

We think our profundity ends with sex,

but it only begins there.

Maybe between longing and belonging

we can be happy with something else.

Strangeness.

Where coincidence becomes grace.

February 16, 2019 / mascara / 0 Comments

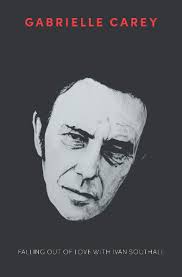

The Discomfort of Self-Recognition

For many years, books have documented the

literary rivalries of writers—Ernest Hemingway and F Scott Fitzgerald, Gabriel

García Márquez and Mario Vargas Llosa, A. S. Byatt and her sister Margaret

Drabble—but Gabrielle Carey’s novella length book Falling Out of Love with

Ivan Southall (2018) is the first I’ve read to examine what happens to

somebody when they lose faith in the writer who convinced them to become one in

the first place. Many of its most interesting elements exist in its story

architecture, a part-memoir of Carey’s writing life, part-biography of Ivan

Southall that critiques his novels and career. To call his career a legacy,

however, may perplex contemporary generations of readers and writers, for whom

the name rings no bells. For modern readers, his reputation and writing has

truly faded into obscurity. By his death in November 2008, Southall was essentially

forgotten: “although mostly unread and unknown to young people of the present

generation, in the 1960s and 1970s Ivan Southall was a literary superstar.”(Carey;

p6) During his prime he produced over thirty books for children and was the

only Australian to be awarded the Carnegie Medal. How, then, does Australia

continue to suffer from this cultural amnesia?

Ever since Puberty Blues (1979),

Gabrielle Carey’s work has been confessional, exploring with her candour the

realities of personal and familial loss, often seeking sanctuary and counsel in

reading and writing. This

eagerness to discern real life meaning and purpose from text is central to her book Moving Among Strangers (2013),

in which she traces her family and her mother’s connection to the enigmatic

West Australian, Randolph Stow. At a time when Joan was dying from a brain tumour, and

Stow is living in exile, Carey

sends him a personal letter. Letter writing was integral to the literary life

of Ivan Southall, too, a similarity that made her immediately align with, and

become wary of, her ex-idol. In many ways, Carey’s latest

is a dismayed retrospective on what it means to devote oneself to a life of

writing. “Maybe the reason I no longer love Ivan the writer is because I no

longer love the writer in myself,” (p64) Carey writes. These tensions, between

childhood literary obsession and disenchantment later in her career, confront

what Carey dubs “self-delusion” and consequently produce a book that evades

definition. A sense of dread occupies each page, and as this negativity teeters

on self-loathing we realise that Carey’s “late-life crisis” is being fuelled by

a common anxiety: the belief that literature is an echo-chamber, pointless,

masturbatory, meaningful only in of itself: “My growing sense of the writing

vocation as useless and unproductive in comparison to nursing or even landscape

gardening is integral to my late-life crisis. It is hard to maintain one’s

sense of self-value if your product, so to speak, is not in any way necessary

for society to function.” (p39) To call this book literary criticism, however,

seems a misnomer, and likewise the memoir and biographical aspects precipitate

in the understanding of the texts themselves. Thus, Carey has found herself in

a bind: to explain why literature may no longer be able to provide meaning and

purpose in her life, she uses that very thing.

Throughout the mid to late 20th century, Ivan

Southall was for many young Australian readers a kind of literary hero, best

known for his survivalist novels Hills End (1962), Ash Road (1965),

To the Wild Sky (1967), and Josh (1971), his Carnegie Medal

winning novel. Nine-year-old Carey was so enamoured with To the Wild Sky that

she decided to pursue the “deliberately difficult” writer life. While

researching this book, she confirmed her suspicion that she wasn’t the only

young reader to be touched by the Southall phenomenon. Her research took her to

Canberra’s national archives, where she uncovered the immense letter

correspondence Southall received from young fans, discovering that “at the top

of each letter in Southall’s handwriting is the word ‘reply’ and a date. No

correspondence, as far as I can see, fails to receive a response.”(p11) Carey’s

re-reading of To the Wild Sky, the book that spurred her to pursue

writing, proved disillusioning. Rather than rekindling her predilections, it

awoke a “palpable dislike” (p35) for Southall, who she not only considers a

mediocre craftsmen but also a cruelly dismissive workaholic who neglected his

own children. “While busily writing to and for his thousands of child fans,’

Carey writes, “Southall’s own children were locked out of his study and,

largely, out of his life.” (p42) This disenchantment culminates in her own

existential unease, “I have also found myself, at times, more devoted to my

writing than to my children.” (p56) In other words, perhaps Carey wrote this

book because she was afraid of becoming like Southall, a writer who tried to

turn the real world into a big fat metaphor in order to escape from it. “Is

this why Southall makes me feel uncomfortable?” Carey ponders. “Because, as a

confessional writer, there is something that Ivan Southall and I have in common?

Perhaps my discomfort is really the discomfort of self-recognition.” (p64)

Nevertheless, at times Carey

can’t withhold a degree of professional admiration for Southall’s devotion to

the craft—the very same austere discipline that produced his selfish workaholic

nature. “Southall was that very rare of writers, a genuine professional,

scraping by from one royalty cheque to the next.” (p23) This admiration

manifests especially in his letter-writing to fans (Carey herself being

terribly fond of the art). Like Carey, many young readers were inspired to

become writers after reading Southall’s books. One young boy by the name of

Peter pens the following letter, reproduced in Carey’s book:

Dear Mr Southall,

I’m writing a story called “The Visitors from Outer Space.” It will be a good story if I can find it and finish it. It’s lost around the house somewhere. How do you keep your mind on your work? Once I start working on something I hardly ever finish it. (p11)

While the digital age has made our idols seem

infinitely nearer, seldom do emails seem to reach beyond a secretary, automated

reply, or the dreaded oblivion of silence. Southall’s reply to Peter’s letter

is also copied in the book:

Dear Peter,

What you must do is use a notebook or exercise book for your stories and put a bright red cover on it. The only way to finish anything, Peter, is to keep on going until you get to the end. There is simply no other way. (p11)

Southall’s directness resonates with Carey’s

sensibilities. As a teacher of creative writing for over twenty years, she

would never dare offer “this most obvious advice . . . [Students] have paid

good money for this secret, which is why so many feel disappointed when they

realise there there is no secret except keep going.”(p12) I’m still learning,

Michelangelo was fond of saying; no doubt Carey and Southall believe the same

to be true of writing. “I can’t believe I have spent so much of my life hunched

over a desk and yet still do not know how to write,” (p97) Carey writes.

At this book’s core is an

examination of the reach and extent of idealisation. Once Carey finally re-read

To the Wild Sky, she was loath to discover it was not particularly

well-written, “the dialogue is clunky, the gender roles stereotyped, the

grown-ups mostly mean-spirited and unlikeable and there is an uncomfortable

obsession with class.” (p34) What can be taken away, then, from a book that

explores a peculiar experience of the literary doppelgänger is that seeing

yourself in somebody else not only causes the fear of unoriginality but, more

tragically, the suggestion that you have lost part of yourself along the way.

Maybe the value of falling out of love with a literary idol is the recognition

that is was never really about them in the first place, and that, in Carey’s

words, “the real nature of the reader-writing relationship [is] one of a

long-distance, non-physical love affair. And if so, maybe it represents the

ultimate, ethereal, transcendent love, independent of the material world. A

love that is purely spiritual, that both children and adults can experience.

The only love, perhaps, that is truly perfect.” (p90)

JACK CAMERON STANTON is a writer and critic living in Newtown, Sydney. His work has appeared in The Australian, Southerly, The Sydney Review of Books, Neighbourhood Paper, Seizure, and Voiceworks, among other places. His fiction has been twice shortlisted for the UTS Writers’ Anthology prize. He is a doctoral candidate at UTS.

February 15, 2019 / mascara / 0 Comments

Anna Kazumi Stahl is a fiction writer based in Argentina. She holds a PhD in Comparative Literature from the University of California, Berkeley, with a dissertation on transnational (East-West) identities in South American, U.S. and German literatures. Her current research explores South-South and East Asian-South American transnational cultural expressions in literature and visual media.As a fiction writer, she works almost exclusively in Spanish. Her book-length works are: Catastrofes naturales (Editorial Sudamericana, 1997) and Flores de un solo día (Seix Barral, 2003), the latter a finalist for the Romulos Gallegos Prize. Stahl’s fiction has appeared in anthologies and journals in Latin America, Europe, Japan, and the USA. She is currently completing a novel based in Buenos Aires, in the southern neighborhoods where historically an Asian immigrant enclave took root and later other immigrants and regional migrations passed through.

The Crab and the Deer

Ten days ago my brother came back from the war. Two days ago they let me see him. He is sick, and has wounds that haven’t healed well. He has a bad fever and it makes him say things in his sleep. He’s been having nightmares. I can see from his eyelids how the monsters slink around inside his head, hurting him. But there’s nothing I can do. I can’t wake him; they’ve explained to me how dangerous it is to wrench a person with a sick heart and lungs out of a deep sleep. And I can’t reach the ghosts that are hunting him. So I sit and stare at his eyelids, where I’ve seen them moving. I try to send him as much strength as possible, so he can defend himself.

This is the first time I’ve ever met my brother. I’ve never met him before because he went away to military service when I was still inside mama’s belly.

The war ended. Finally. It ended not long ago. I say finally because it lasted a very long time, years and years. On the radio they announced “the end of the conflict” and people went out into the streets to discuss it in more detail, I guess. But nobody celebrated. That’s because we lost; as a country, we lost, and as people, each one of us lost too. Amputee is a word I learnt. So many of the things we had before are now missing: a mother is missing, or a father; a son, a brother, a cousin; houses are missing, and hands, and eyes. When peace came there was a lot of fuss. The city overflowed with people looking for work, food, medicine. Because they come from other parts of the country, the people speak funny and act different. But my brother also re-appeared.

I don’t know why there are wars, I don’t know what they’re for, but as soon as my brother wakes up I’m going to ask him. He’s the only person I know who actually fought in the war – as a conscript, they told me, which means he didn’t want to be sent, but he was sent anyway, and that’s why I think he must know something and can help me answer my questions.

For now, he sleeps all day and all night. He seems to be resting, but I hear the doctor talking to my father and he says something about a rapidly accelerating infection. The words sounds mechanical and I don’t understand how to relate them to my brother. I don’t have anyone to explain them to me (mama died in the first round of bombings, when everything was just beginning, and I don’t want to annoy my father – I’m afraid of how he might react, especially now that we’ve lost the war). It’s better if I try to figure it out on my own. That’s why I listen to everything, even though I don’t always understand it.

A nurse comes in with the doctor. I have to leave my brother’s room while she works. I hear water splashing and in my mind I see the nurse rinsing a small white towel to refresh my brother’s face and hands. But he doesn’t wake up.

When they let me back in, I sit in a corner while the doctor examines my brother. The doctor gives him medicine, and writes some notes down on a form that he then puts into a briefcase. When he’s finished I get closer. My usual place is right next to the bed, at head height. I watch my brother sleeping. There are things I didn’t see the first few times I visited, but now they are very clear. I—— has the same eyebrows as mama, thick in the middle and long, reaching almost to the temple. His forehead is like our father’s, and his mouth, too; the same fine, delicate lips, almost like they’ve been drawn in pencil. When I notice these traces of mama and papa in my brother’s face, I realise that he and I must look alike. I go to the mirror near the entrance, with the door open so I can see myself properly in the daylight, and it’s true. The eyebrows, the nose, the mouth – the similarity is there. Nothing else is left of our mother; we have her big cooking pots, her tea set, the little box of needles and thread, a basket with remnants of different-coloured fabrics, things she used to use and now nobody uses. But that small detail in my brother’s face, and in mine – the form of the curve above our eyes – means mama is still here, somehow.

When I’m in his room my brother has a nightmare: the globes of his eyeballs roll around behind the closed lids, and suddenly he opens his mouth so wide that a wound on his lip splits open and starts to bleed. He makes a strange sound, like a boiling kettle, and then screams: “Crabs! Save me!” He is still asleep but he arches his back and throws his head back so far that it looks like he’s about to break his neck. I don’t know what to do. I put my hands on his chest and push; as I’m doing this, another part of my mind thinks that my brother’s chest is like the wooden washboard we use for washing our clothes, with its deep grooves, and I realise this just means my brother is skinny, but then I get the thought that my brother might be turning into a machine, or an object, and the thought scares me. A moment later, the violent tension is gone. My brother goes back to how he was before, quiet and still, breathing deeply with his eyes closed. I look at him for a while until I also feel calmer. Before leaving, I clean the wound on his lip.

The doctor and the nurse don’t come for several days. Maybe my brother is better. He’s still asleep, but he hasn’t had any more fits or nightmares. Is he better? I visit him after we’ve taken our tea. He is very still. He seems to be breathing, but I can’t be sure. I approach him and touch his skin. He is freezing. I make a tent with my hands over his shoulders and breathe into it. My breath warms his chest. But his chest is only small, and he is big. By the time I reach his legs, his chest will be cold again. I don’t have time to go to the hospital for help; by the time I get back he’ll be worse, he’ll have turned to wood or ice or evaporated into steam, like a ghost. But as I’m thinking all of this the nurse and the doctor arrive, I don’t know if by chance or by good luck, but they arrive and I say: “Just in time!” They don’t say anything in reply, and they don’t turn to my brother, either. They grab me and force me to the ground. The nurse washes my hands with alcohol. She tells me I won’t be able to see my brother or anyone else for a week. I have to be quarantined.

I spend the week locked in a bedroom. The blinds are always down and eventually I lose track of how many days have passed. I watch the light at the borders of the windows, and think about the movement of the sun.

*

Today my brother is awake. I can’t believe it, but there he is, awake. When I enter his room I see a cup of tea in his hand, which is almost empty. I feel relieved that he’s drunk so much of the tea. It’s proof that he is better. I approach his bed and speak to him softly, in case he’s still not used to loud noises, but I feel an urgent need to know what happened, what he saw, what he did, because if I know then maybe I can figure out the solution, the cure.

“Brother,” I whisper. “Please tell me, Brother. Why are you like this? What was it that hurt you?”

He looks at me. He seems to know who I am. Now that his eyes are open, I don’t have to look in a mirror to see that we look alike.

“In war,” he says, looking at me the whole time, “doesn’t matter if you win or lose, you end up sick. If you want to learn something about life, Little Sister, you’re better off asking the animals. Forget human beings. That includes me. Forget about me.”

I’m horrified. “No!” I cry, and the nurse comes to separate us, to calm him down and to calm me down. But I don’t stop: “No, never, I won’t forget you! Do you hear me? Never!”

“You should go, Little Sister. I want to sleep.”

The nurse doesn’t have to escort me out – I respect my brother, so I leave. I go out into the garden. It’s a humid afternoon, warm. I can hear the toads singing, the birds, the odd cricket. I’m confused and worried by what my brother said.

Then, one morning, I run away. I can’t stop thinking about him. I know how easy it is for someone to die. I decide to take his advice: I’ll go and talk to the deer in the park of the old Temple of Dreams. They roam freely there, because they’re not regular animals, they are the messengers of the gods. I know this from reading a lot of kids’ books, and from my religion lessons, and now after what my brother said I think it might be true after all. Anyway, it’s the only option I have. If I don’t ask the deer, I’ll have to go back to depending on my father and the doctor and the nurse.

Sneaking out of the house is easier than I’d feared; nobody comes to stop me, or even asks what I’m doing.

As soon as I enter the park I start to feel dizzy, so I close my eyes and lean closer and closer to the ground until I’m squatting there. I think I might have a rest, but then I hear the heavy footsteps of an animal coming along the gravel path. With my eyes still closed, not daring to stand, I stretch out one of my hands. Nothing. Just air. I lift my hand a little higher and my fingers brush fur. There are only deer in this park, so it can’t be anything else, but how am I supposed to know if it’s The Deer? The deer who carries the message for my brother and I? As I’m thinking this I start to get a hot feeling. The deer is radiating heat, but not a heat like my brother’s fever – it’s like an internal force transforming into something that I can touch with my hands. I open my eyes and see the enormous, dark brown body. I am crouching right next to one of its front hooves, looking towards its stomach, which is like a big orb, because it is round, or like a planet, because it seems to have its own force of gravity, which pulls me to it like a magnet. I rest my cheek, my right hand, my shoulder against the deer’s body; I let my whole weight fall against it. And then I feel how the heat invades me, entering through the palm of my hand and travelling through my wrist, moving up my arm towards my shoulder, filling my lungs, my heart, my whole belly, and continuing to pulse into my legs, my ankles, right down into the soles of my feet. Suddenly all of me is strong, and I am shining – I can’t see it, but I’m sure I am because of the sensation – like a tiny sun.

Then, in a clear and melodic voice, as if singing it to me, the deer gives me the message: Put your eye into the crab and be like him. He adapts to the earth and the sea. He looks ahead and walks towards the shore. He sees everything one hundred times, and he is not bothered by any of it.

I keep listening but the deer doesn’t say anything else. Suddenly the strength leaves me, and it’s as if I am deaf. I blink in the midday sun. My deer has left. I didn’t even see him go.

The next time I speak to my brother, I don’t ask him about his experiences. I tell him about mine.

“I went to the park of the Temple of Dreams. To see the deer. And it was easy, one came to find me. He told me I have to be like the crab.”

“Ah, of course,” my brother replies, in a strange tone I now recognise as irony. “You have to follow his lead. Like Robin Hood.”

“Who is Robin Hood?”

“A Nobody. A character from long ago.”

“And who is the crab?”

“Who? No. What is it? It’s an amphibious crustacean.”

“I know that: it adapts to the earth and the sea. The deer told me. And why is that good?”

“Because, even if your environment changes, you survive. It’s like Confucius said: When things get bad, don’t act; hide.”

“Isn’t that what cowards do?”

“No. It isn’t.”

“Have you seen any?”

“Any what?”

“Crabs. Have you seen any?”

He hesitates before answering. After a while he says: “Yes, but they weren’t alive.”

“Where did you see them?”

“South of H——, in a barrel that was used to trap them, but it had been left on the beach for many days, weeks even, so they rotted in there.”

“What were you doing with a barrel like that?”

“No, I got inside it. I was in a barrel like that.”

“Why?”

“To get away from the war, to hide until peace came. Or to die, whichever came first.”

*

A little while later, he is sicker again. For several days they don’t let anyone visit him. The doctor comes and goes. In the evening I hear the voice of the priest who looks after our family. When I go to see my brother the nurse tells me to act as if everything is fine, because that will give him the strength to get better.

I ask him: “Are you the crab?”

“You tell me. The deer spoke to you. It didn’t tell me anything at all.”

Suddenly, I’m not sure why, I start whispering to him quickly, telling him what I’ve heard here in the house: “Everyone here – the doctor, the nurse, even papa, thinks you’re going to die, but not me. I know you are the crab and you’ll come walking out the other side.”

The next morning he wakes up feeling good. Strong, lucid. He gets out of bed. The first thing he does is go to the garden. Then he gets dressed and says: “I’m going out with my little sister. For a walk, then we’ll come right back.”

He shows me the indoor market. I see some enormous buckets with a sign that says CRABS, and I ask to look at them up close. The crabs have tiny spherical eyes, like black beans, sitting on top of these flexible sticks that point around all over the place.

“Look at their eyes!” I say to my brother, excited by the discovery. “Are they blind?”

“No, actually they can see very well.”

“That’s right, I remember: they see everything one hundred times. Why is that?”

“I’m not an expert on crabs, but I know their eyes are formed sort of like prisms, and they capture images from many different angles. I learnt that back in high school, before the war. You’ll learn it too, now that you’re going back to school. Make the most of it.”

“What else can crabs do?”

“That’s enough for now. Let’s go for a walk. You ask too many questions. It’s not good for you to be so stuck on one thing. It’s not worth the effort. Look around you” – and he points at the young women standing near us, carrying their babies on their backs and baskets of vegetables in their hands, or the old women balancing loads wrapped up in fabric on their shoulders, or the young girls less fortunate than me selling rags in the street, trying to earn some money or trade something for a bowl of rice. “You have to get those ideas out of your head, Little Sister. Don’t go back to see the deer. Go to school and pay close attention to everything they tell you. Don’t believe all of it, but listen, investigate it as deeply as you can.”

After that day, my brother has a terrible relapse; his cough turns violent, his fever won’t go down, and blood comes out of his nose and mouth. Our father calls the doctor. In a calm but serious voice, the doctor tells us my brother won’t live through the night. Later I hear my father talking to the doctor; he asks if it’s really worth buying his son a cemetery plot and engraving his name of a piece of marble, since in the end he was nothing but a failed soldier.

I spend the whole night waiting outside my brother’s room, listening to the fierce, awful sounds of sickness. Then I don’t hear anything. It descends in an instant, or at least that’s how it seems: a silence that freezes me to me bones. I try to stand up but I fall to my knees; as I open the bedroom door my hands are clumsy, like gloves filled with stones. The room is semi-dark. The silence echoes off the walls like an earthquake. A voice inside my head says: Prepare yourself. You are the first person to see him. Prepare yourself for that, and for what comes next. But when I get to the bed, I see it is empty. The first light of the morning is just appearing at the window, and I can see him standing there, looking out. He turns and smiles at me, but I am frightened, because he is shining; I know he is shining, even though at the same time I want to doubt it, to deny it. The light is fine and soft, like a sun shower or the reflection thrown by the moon. He comes towards me and crouches down to tell me something in a soft voice; he smells like soap and cotton, and cough medicine. He whispers: “I’m all right. Don’t tell anyone.” His voice is clear, and he smiles at me again.

Surprising, incredible, says the doctor when he sees my brother later that morning. I listen silently. My brother starts walking around the room as if trying out his body. I watch him, his hair falling over his forehead, nearly reaching his eyebrows, and I see him concentrating, biting his lip like mama used to do when she was sowing. I don’t want to leave him ever again. Everything he does gives me strength, too, or something like strength. Sometimes the feeling reminds me – though it is much less intense – of when the deer gave me his energy.

A few days pass. My brother still hasn’t left his room (the doctor won’t let him) but one morning I go to see him and all his things are packed up. Some things – most of them – are in boxes, ready to be thrown out, and the rest is in a small bag sitting inside the doorway. His hands are dirty; there is a black crescent moon beneath every fingernail, and his knuckles have traces of ink or oil on them. I bring the washbowl to him so I can wash his hands, but he does it himself so I just watch, taking in every detail: the shallow pool of water at the bottom of the bowl; the hard, off-white soap; the old scrubbing brush with its yellowed fibres; the discoloured but clean hand towel, which has been dried in the sun. I notice the way he does everything carefully, as if learning it for the first time. He scrubs his sudsy hands without splashing the water, he cleans each nail one by one, and presses his thumb into the palm of his hand as if feeling for the many tiny bones and tendons beneath the surface. Then everything is put away neatly: the soap and brush don’t drip any water or create any puddles, and he dries his hands with slow, precise movements. When he’s finished he says, not to me but to the room, to the air: “So pure, and so simple.” And in that moment I know that his good health will stay with him forever.

He leaves the house before his scheduled medical check-up. I go with him.

*

At first we earn a living helping with the fruit harvest. Whenever we can, we take the train into the capital to visit the central market. We go there to buy crabs, as many as we can carry, and we take them home alive; we don’t plan on eating them. The fishmonger doesn’t know that. He thinks they’re destined for the cooking pot. I smile at the fishmonger, especially if he says: “Enjoy!” It makes me happy. I love those crabs. Then smell good, like the sea, like the Inland Sea of my country (which, by the way, has no more armies – no army of its own, and no occupying armies). I love my brother. He knows how to live, and he’s teaching me, and that’s the most important thing.

‘De Hombres, Ciervos y Cangrejos’ (‘Of Men, Deer, and Crabs’)first appeared in ADN Cultura, Cultural, La Nacion, 26 January 2008, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Translated from the Spanish by Alice Whitmore.

ALICE WHITMORE is the Pushcart Prize and Mascara Avant-garde Award-nominated translator of Mariana Dimópulos’s All My Goodbyes and Guillermo Fadanelli’s See You at Breakfast?, as well as a number of poetry, short fiction and essay selections. She is the translations editor for Cordite Poetry Review and an assistant editor for The AALITRA Review. Her translation of Mariana Dimópulos’s Imminence is forthcoming in 2019 from Giramondo Publishing.