The Burial by Bijan Najdi translated by Laetitia Nanquette & Ali Alizadeh

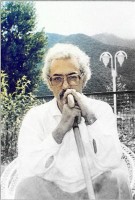

Bijan Najdi (1941-1997) was an Iranian poet and short-story writer, famous for his collection The Leopards Who Have Run With Me (1994), from which the selected short-story “The Burial” comes from. His style is characterized by the use of unfamiliar and poetical images offering a fresh perspective on the everyday world.

Bijan Najdi (1941-1997) was an Iranian poet and short-story writer, famous for his collection The Leopards Who Have Run With Me (1994), from which the selected short-story “The Burial” comes from. His style is characterized by the use of unfamiliar and poetical images offering a fresh perspective on the everyday world.

The Burial

Translated by Ali Alizadeh and Laetitia Nanquette

Taher stopped singing in the shower and listened to the sound of the water. He watched the water flow down the sagging skin of his thin arms. The smell of soap dripped from his hair. Steam encircled the old man’s head. When he threw the towel around his shoulders, he felt as if parts of his body’s old age stuck to the long red towel and the swollen veins of his legs stopped throbbing. He buried his head in the towel and lingered by the door of the bathroom until he started to feel cold. Then he dragged himself to the mirror of the main room and saw that he was indeed an old man now.

In the mirror, he could see the breakfast spread on the floor and Maliheh’s profile. The samovar was boiling, silently in the mirror and loudly in the room, and Taher and his image in the mirror warmed up to it.

Maliheh said: “Don’t open the window; you’ll catch a cold, ok?”

Friday was behind the window with its incredible resemblance to all the winter’s Fridays. An electric line was bulging under the blackness of birds. The curtain dividing the main room was motionless and the wood-burner was burning to the song of the sparrows. Taher sat down for breakfast, switched on the radio (…with minus 11, theirs was the coldest part of the country), and raised a glass of tea.

Maliheh, turning her face towards the window, said, “Listen, it sounds like there’s something going on outside.”

Their home had a balcony overlooking the only paved street of the village. Twice a week, the sound of the train arrived, passed the window, and ended up on the broken pieces of the plasterwork of the ceiling. On the days when Taher did not feel like reading the old newspapers, when the smell of the old paper made him feel sick and when Maliheh was too tired to sing the forgotten songs of Qamar through her dentures, they went to the balcony to listen to the sound of the train, without ever seeing it.

“I’m talking to you, Taher. Let’s see what’s going on outside.”

Taher put down his glass on the tablecloth and went with his wet hair to the balcony, his mouth full of bread and cheese. There were people running towards the end of the street.

“What’s happening?” asked Maliheh.

She was more or less sixty years old. Thin. Her lips had sagged. She did not pluck her facial hair anymore.

“I don’t know.”

“I hope it’s not a corpse again… They must have found a corpse again.”

Even if Maliheh had not said “a corpse again”, they would have continued to eat their breakfast remembering the hot and sticky summer day when they had argued about the choice of a name: the day when the sun had crossed the frontier of Khorasan, lingered a bit on the Gonbad-e Qabus tower and travelled from there to the village to spread a pale dawn on Maliheh’s clothesline.

Taher, in the bed saturated with Sunday’s sun, had woken up to the music that Maliheh’s feet made each day. Maliheh would soon open the wooden door, and then she did just that. Before putting the bread on the breakfast spread, Maliheh said:

“Get up, Taher, get up.”

“What’s happening?”

“At the bakery, people said they’d found a corpse under the bridge.”

“A what?”

“A dead body… Everyone’s going to have a look at it, get up.”

The two of them walked towards the bridge. There were people standing on it and looking down. For such a crowd, they were not making much noise. A warm wind was blowing towards the mulberry trees. A few young men were sitting on the edge of the bridge with their legs pointing down to the sound of the water. The police had formed a circle around a jeep. As soon as Maliheh and Taher arrived at the bridge, the police placed the corpse into the jeep and drove away.

Maliheh asked a young girl: “Who was it, my dear?

“I don’t know.”

“He was young?”

“I don’t know.”

“You didn’t see?”

The young girl moved away from Maliheh.

A man leaning on the railing of the bridge said: “I saw him. He was all blown up and dark. It was a kid, Mother, a little one.”

Taher took Maliheh’s arm. The bridge and the man and the river swirled around her. All that could be seen of the jeep was some dust moving towards the village.

“This man called me Mother, did you hear Taher? He called me…”

The sun had set. There was a little triangle of sweat on the back of Taher’s shirt.

Maliheh said: “Where are they taking this kid now? Was he dead? Maybe he was in the water playing and then…” The warm wind had failed to ripen any mulberries and had come back to ruffle Maliheh’s chador. “I didn’t find out how old he was! Take my hand, Taher.”

“Let’s sit down for a bit.”

Maliheh was thinking, if only there were children here instead of all these trees. “Ask someone where they’re taking him, will you?”

“Probably to the police station or to the clinic.”

Maliheh was thinking, if only I could see him.

Taher added: “What is there to see anyway, it’s just a kid.”

“That’s what I’ve been telling you.”

“You want to go and see Yavari?”

The doors of the clinic were open. There was a row of tall pine trees in the alley leading to the building’s landing, so dry that summer paled to insignificance next to them.

Doctor Yavari shook Taher’s hand and asked Maliheh: “Have you been taking your pills?”

“Yes.”

The doctor asked Taher: “Is she sleeping well at night?”

Maliheh interrupted: “Doctor, they’ve found a child. Do you know about this?”

“Yes.”

“Where is he now?”

“They’ve put him in the storeroom.”

“Storeroom? A kid? In the storeroom?”

“You know we don’t have a morgue here.”

“What will they do with him?”

“They’ll keep him ‘til tomorrow. If nobody comes to claim him, well, they’ll bury him.”

“If nobody comes, if nobody claims him, can we take him?”

“Can you… what?”

Taher said: “Take the child with us? What for, Maliheh?”

“We will bury him, we will bury him ourselves. Maybe then we can love him. Even now, it’s as if, as if… I love him…” Maliheh buried her head in her chador and the cry that she had kept from the bridge to the clinic broke out and her thin shoulders twisted under her chador and she blew her nose into her covered fist.

Taher poured a glass of water. The doctor had Maliheh lying down on a wooden bench. He stuck a thin needle under the skin of her hand. A bit of cotton with two drops of blood fell in the small bucket near the bench and until sunset that day, until the not-passing of the sound of the train, Maliheh did not open her eyes and did not say a single word.

It was Friday. The curtain of the main room was motionless and the wood-burner was burning to the song of the sparrows. The white winter, on that side of the window, wandered with its white coldness.

Maliheh said: “So many names, but nothing in the end.”

“We will eventually find one.”

“If we couldn’t find a name that day, then we can’t. Which day of the week was it, Taher?”

“The day when we went to the bridge?”

“No, the following day, when we went to the clinic…”

The day following that Sunday nobody came to claim the corpse. So on Monday, they sent the corpse from the clinic to the cemetery, carried on a crate, rolled up in a grey sheet. Outside of the clinic’s courtyard, Maliheh and Taher, who were not dressed in black, in a weather that was neither sunny nor rainy, started to walk at a slower pace than the man who carried the crate, who changed it from one hand to the other from time to time and sometimes rested it on the ground or against the trunk of a tree. They went around the small square of the village and entered its sole street. In front of the coffeehouse, the man rested the crate under a lamppost, which, although it did not look at all like a tree, was casting a shadow on the ground just like one. The coffeehouse keeper poured water from a jug and the man washed his hands and stayed at the same place to drink a glass of hot milk from the saucer. Maliheh turned her head and felt something leaking from between her breast to her shirt just as she walked past the crate. Taher slowed down his pace. Even though their house was nearby, Maliheh and Taher did not return home and stood still until the man was ready, for they did not wish the break the solemn silence of the funeral procession. They even stopped and looked at the balcony of their house where the window was still open to let the sound of the train enter, and they saw a young Maliheh bending to pour water in a flowerpot. When she lifted her head, an old Maliheh was gathering the empty flowerpots. Maliheh, with her firm flesh and her dark hair loosened, opened the curtain. Maliheh, with her small face and her hair tainted with henna, was walking in the rain. It rained just a few drops and then the man entered the cemetery. Taher and his wife had walked over the grass between the stones, a few steps away from the house where the corpses were washed. The burial ceremony—grey, dusty—lasted so long that they eventually had to sit down on the wet grass. When the gravediggers left, one could still hear the sound of the spade.

Taher said: “Get up, let’s go.”

“Help me then.”

They held on to one another. One could not say which one was supporting the other. As they struggled to stay on their feet, Maliheh said: “So he belongs to us now, no? Now we have a child who’s dead…”

All around them were stones, names and dates of birth…

Maliheh added: “We must tell them to carve a stone for him.”

“Ok.”

“We must find him a name.”

“…”

“…”

It was Friday; the wood-burner was burning to the song of the sparrows and from the balcony one could hear the hubbub of the people echoing from the other end of the street. They were making so much noise that Taher and Maliheh could not hear the sound of the train, approaching, passing, disappearing.

***

LAETITIA NANQUETTE is a French translator and academic, based at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, specializing on contemporary Iranian literature and World Literature. She frequently travels to Iran.

LAETITIA NANQUETTE is a French translator and academic, based at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, specializing on contemporary Iranian literature and World Literature. She frequently travels to Iran.

ALI ALIZADEH is a Melbourne-based writer and lecturer at Monash University, and is co-editor and co-translator, with John Kinsella, of Six Vowels and Twenty Three Consonants: An Anthology of Persian Poetry from Rudaki to Langroodi

ALI ALIZADEH is a Melbourne-based writer and lecturer at Monash University, and is co-editor and co-translator, with John Kinsella, of Six Vowels and Twenty Three Consonants: An Anthology of Persian Poetry from Rudaki to Langroodi