Tim Wright reviews Mogwie-Idan Stories of the Land by Lionel Fogarty

Mogwie-Idan Stories of the Land

Mogwie-Idan Stories of the Land

by Lionel Fogarty

ISBN 978-1-922181-02-2

Reviewed by TIM WRIGHT

Arguments for the importance and power of Fogarty’s poetry have been made by a number of writers since the 1980s. Some prominent examples are: the forewords to Fogarty’s first two collections, written by Cheryl Buchanan and Gary Foley respectively, Mudrooroo’s early critical attention and championing of his work, Philip Mead’s comparative reading of Fogarty (alongside ΠO) in his study of Australian poetry, Networked Language (2008), John Kinsella’s statement in the 2009 Penguin Anthology of Australian Poetry (and quoted by Ali Alizadeh in the introduction to this volume) that Fogarty is ‘the most vital poet writing in Australia today’, and Stuart Cooke’s reading of Fogarty’s work in his recent comparative study of Australian and Chilean poetry, Speaking the Earth’s Languages (2013). At almost 160 pages Mogwie-Idan announces itself as a major collection. It is also a generous one, containing the poems of the earlier published chapbook Connection Requital along with the 50 poems of Mogwie-Idan, and a susbtantial selection of Fogarty’s drawings.

The range of subjects Fogarty’s poetry deals with is informed by his many years involvement (since the mid-1970s) in Aboriginal activism, and direct references to this history appear in poems such as ‘Tent Embassy 1971-2021’. About the subject matter of his poetry Fogarty is unambiguous; in an interview with Michael Brennan he says, ‘Deaths in Custody is the most important subject in my poetry, as well as Land Rights and general struggles of national affairs.’ Political matters such as these are entirely personal for Fogarty, as they are for many, perhaps all, Aboriginal people. One need only read Fogarty’s author biographies to learn that state repression has been a part of his life. The most extreme manifestations of this would be the charges made of conspiracy against the state, as part of the ‘Brisbane Three’ in 1974-75 (the three were acquitted), and the death of his brother, the dancer Daniel Yock, at the hands of police, in 1993. As has been described by himself and others, the protest of Fogarty’s poetry is taken into the fabric of English; it can be seen as an attempt, as he has said, to conquer, or crush, English.

The poems draw from Munultjali dialect (for which a glossary is provided), however the poetry’s most radical linguistic element is its frequent a-grammaticality, its torquing of conventional English syntax such that, for example, nouns are rendered as verbs and vice versa, or ‘wrong’ verb forms are used. Sabina Paula Hopfer writes that in reading Fogarty’s work she is ‘made to understand what language genocide feels like rather than what it means in abstract terms.’ She writes that Fogarty’s words, referring to two of his early collections, ‘pound down on the non-Indigenous reader like hail stones, so that the reading experience is one of complete exhaustion and despair.’ I have remembered this description of Fogarty’s work since I first read it nine years ago. While I believe the metaphor of hail is an accurate one to carry the force of Fogarty’s poetry, I now to think that Hopfer’s reading of it risks overemphasising the response of despair. What about the exhilaration of reading the poems/getting hit on the head with hail? I would want also to emphasise the potential dialogic space that is created by the linguistic complexity of Fogarty’s poetry, one that a reader is required to work towards. Michael Brennan argues that Fogarty’s manipulation of English obliges reciprocity of the reader, and so, the possibility of dialogue, writing that his poetry ‘can be seen not simply as a counter discourse but as an integrated, less dialectically defined, reconception of English – literature and usage – wherein a reciprocal biculturalisation is demanded of the colonisers.’

‘Connection Requital’, the opening sequence, is a blast of nine poems written entirely in capitals. Fogarty’s formal decision to use capitals only in this sequence appears to mark a new degree of urgency in his work – significant given the sense of urgency his poetry has always contained. In ‘Mutual Fever’ the tone is almost biblical – or bushfire scene – in its intensity and imagery:

A WATERLESS SEA OF ASHES

FIREFLIES ROARED LIGHTS AROUND A SMALL BUSH

BLAZING CARCASSES MOANED TO BE DREAMT

PRE-DAWN STAGGERED WITH ONE MAN

WHO DRANK GLOBULES FLOODED WATERS PURE AHAHAH

The longest poem in the book, ‘Wisdom of the Poet’, is for the Chilean-Australian poet Juan Garrido-Salgado. It demonstrates the strategic function inherent in Fogarty’s songman and spokesman roles. In this case, the poem is a message of solidarity across different cultures. But it is more than this – ‘Wisdom of the Poet’ moves breezily between the ancestral, and aspects of the current political and economic situation of Aboriginal people. We read reflections on the Mabo judgement, questions of law and culture (‘White women playing our digeridoo instrument / Can’t do nothing, they’re protected by the government’), of Australian Aboriginal history (‘Only 40 years ago / My race of people were suffragettes’), of Aboriginal leadership and media overload (‘TV’s black leaders selling out / zonked out with a sore head / ‘cause watching TV left my brain dead’), and advice to younger generations (‘black people need to be educated white man’s way / so we can know what they write and what they say’). There is much else in this poem that is not as easy to categorise; the second half moves into a different realm entirely, of the personal and spiritual. The final lines return to economics and specifically to the question (still hardly dealt with in Australia) of financial compensation:

We had civilisation before they came

so us know the way to a future

Chile Mapuche we are with you to liberation

The day will come

when all rich classes must pay for crimes

of past and present

You may think this is silly

but we really want compensation

The poem ‘Conducted at Native Religion’ begins with an epigraph from the former Premier of Queensland, Anna Bligh, during the 2011 Brisbane floods: ‘We are Queenslanders, from north of the border. They keep knocking us down, but we keep getting up. . .’. The mawkish ‘battler’-ism of Bligh’s speechwriter’s statement is highlighted when pulled into the context of Fogarty’s poem – as is the irony of Bligh taking on the Aboriginal discourse of survival for a comparatively minor threat to existence (that is, compared to colonialism): ‘Even a full supreme court illegals our public ears / Let injustice be in the hand of those political ‘nit wits’’. An older poem, dated May 1990, ‘Overseas Telephone’, details beautiful collisions of sense, ‘Few always joined with your / intermittent distance / like seasons are intense with / the sun’s radio’. The first half of the poem is in tones that are humorous, chatty, flirty, loving; the images in the second half are violent and extreme:

I’ve been given a violent

foaming hearing

But I never panic when you

cut throats

I am the peaceful liberty love

of political prisoners

Your raped sounds burst

explosions of speeches

Everything endured by me

will inflict my sadness to

love melancholy dart eyes

My silence is not an absence

Your power vultures more despair

I see your horrified voice

You are patriotic to filth

and drink urine mixed with cement

A later line in the poem, ‘I am murdered ten million yesterdays’, might resolve in different ways: ‘I murdered ten million yesterday’ or the very different ‘I murdered ten million yesterdays’ or as two discrete statements ‘I am murdered’ ‘ten million yesterdays’. Ten million yesterdays works out to around 27,000 years. Speaking of time on these kinds of scales is frequent in Fogarty’s work; he is not the modernist poet obsessed with the illuminated ‘moment’. Rather, Fogarty’s diction is often world-historical in scope. Western calendar years flash up throughout the collection, in a parody of chronology: ‘Living here in 2020 sometimes / gives me the 1920’s even 1770’ (‘2020’). The consciousness of history is clear in the title of another poem in the collection, ‘Past Lies Are Present’, which perhaps says enough, though its specificity to Australian politics is clear in the first lines, ‘Past lies are present / A fake sorry is given’.

The poem ‘Decipherer’ is one of the more abstract in the collection:

Uncharted activated waters

reveal unflushed originators.

My true darling breath of exhilarating

vision is acute in testifying customs.

I am I, charted in deliverance by black myriads

codified relations comes of purification.

Global psychic energies only will mark

awareness by Aborigines’ new ages wildfire.

Uncharted harmony and I get accent

ingredients to equivalent windswept.

Reveal flourished in our astrological eyes.

Herd warriors worry no more

History unbalanced kept me ‘dead’ indecipherable.

Future ballad themes honour me

chilly little crystal humour ‘Ha, Ha, Ha’.

To decipher is ‘to turn into ordinary writing’. ‘Decipherer’ may be in part addressed to the reader or critic who would handle Fogarty’s poetry as a kind of cipher or code for which there existed a key that would unlock ordinary writing (whatever that might be). This would be opposed to those understandings of it described earlier by Brennan, as constituting a ‘reconception of English’, and thus requiring the reader to move outwards, further towards the language, rather than trying to draw it closer to her or him. One approach may be to read Fogarty’s poetry guided by a term he has used in interviews, the mosaic: ‘I am mosaic in reading, I nitpick readings. I often read back to front, similar to Chinese’; ‘Most of the time I use words in mosaic of catalysing . . .’. Thus the repeated phrases of ‘Decipherer’ – ‘My true darling’, ‘History unbalanced’, ‘uncharted’/‘charted’, ‘wildfire’ – might be analogous to differently coloured fragments, generating a pattern of concepts or ideas that the poem explores. The mosaic is suggestive too of the way sense is sometimes, as in ‘Decipherer’, ‘scattered’ through Fogarty’s poems, such that they resist line by line interpretations, yet at the same time are held together by their sonic patterning:

Between sound and colour ‘I am a bit’

Between music strangely I’m beyond white time

Affirmation give techniques limitless in my

Plain chant transfiguration musics

Fogarty’s torquing of syntax is also at work in this poem. In the earlier line ‘Reveal flourished in our astrological eyes’, ‘reveal’ can be read as objectified, a quality which ‘flourished’; or, we may read ‘flourished’ as an adjective – ‘with flourishes’ – the object of the verb ‘reveal’. Considered this way, the function of both ‘reveal’ and ‘flourish’ are turned outwards, enstranged. ‘My true darling breath’ is in a Romantic diction that may be parodic. It is immediately torqued, in that, where a reader may expect a noun, following ‘of’, there is an adjective – ‘exhilarating’ – which can be read as enjambed, flowing onto the next line, ‘of exhilarating / vision is acute in testifying customs’, or as a discrete line. Where a rest or the consolidation of an image might be expected, we find the ground hasn’t appeared yet and we have to keep moving. Stuart Cooke, writing of Fogarty’s poem ‘Heart of a european . . .’, describes evocatively this mode of reading that Fogarty’s poetry calls for:

There are portions of grammatically correct English here, but no sooner do they appear than they have dissolved into a kind of word-music. Consequently, those intelligible phrases have the effect of punctuating the swirl of rhythm and rhyme with moments of clarity, which the reader “clings” to, as if stopping at the occasional water hole to rest before moving onto the scrub.

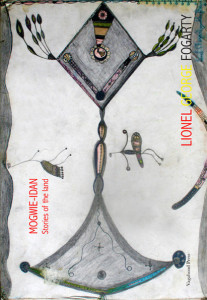

Reproductions of Fogarty’s drawings are throughout the book, and arrive like gifts. While I am aware that these drawings contain meanings for Fogarty and his community not known to me, I attempt here a necessarily limited description. The drawings contain recurring ideas and motifs: mandala-like circles, or wheels; shields, boomerangs or boomerang-like shapes, tendrils or vines and straight ruler-drawn connecting lines between bodies. In many, there is a sense of suspension, of subtle yet firmly and intricately maintained connection between otherwise independent bodies. There is a sense of both organic and mechanical motion; each drawing appears to be a complete system of articulated, or in some way engaged, parts. In the drawing ‘Gauwal (Far away)’ a cord emerges from an orifice within a blob that could be muscle-tissue; half-way down the picture surface this splits into two strings, and from inside the cord another line emerges, resembling rosary beads or a chain. At the base of the picture a solid log is suspended by the cord which divides the picture surface vertically, and on which or within which are various insignia: egg-like shapes connected as if within an intestine, circles, a diamond striated. The drawing is one of the more minimal of Fogarty’s works, most of the picture surface being blank background. The bodies are ‘far away’, as the English part of the title says, yet undeniably connected. Including the image used for the cover, there are twenty drawings in the book, which are each printed to the edge of the page, unframed. The effect is that the drawings come to be placed in a more equal relationship with the poetry, interleaved not supplementary or illustrative.

A Southerly issue of 2002 contains facsimiles of Fogarty’s poems in manuscript, his drawings intertwined with the words of the poems. In Mogwie-Idan the poems and drawings are on separate pages, but there is a broader sense of written word flowing into the drawing and back out again. This relation between word and image is set up in the opening of Mogwie-Idan, which literally invites readers in – ‘Jingi Whallo / Hello how are you all?’ – and goes on to acknowledge the traditional people, ending on an ellipsis which ‘leads’ the eye directly to the drawing on the facing page, ‘Burrima (Fire Man)’. Throughout the book the reader is able to consider analogies between the fully articulated, holistic systems of these drawings and those same qualities present in the poems.

The book ends with the extraordinary poem, ‘Power Live in the Spears’, a kind of chant, which in its insistence recalls one of Fogarty’s influences, Oodgeroo Noonuccal; the cumulative effect of the lines becomes an incantation:

Power live in the spears

Power live in the worries

Power air in the didgeridoo

Power run on the people heart

Bear off the power come from the land

NOTES

1. Johnson, Colin, ‘Guerilla Poetry: Lionel Fogarty’s Response to Language Genocide’, Westerly, No. 3, September 1986, pp. 47-55

2. Brennan, Michael, ‘Interview with Lionel Fogarty’, Poetry International, http://www.poetryinternationalweb.net, July 10, 2011

3. Hopfer, Sabina Paul, ‘Re-Reading Lionel Fogarty: An Attempt to Feel Into Texts Speaking of Decolonisation, Southerly, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2002, p. 60

4. ibid, p. 47

5. Brennan, Michael, ‘Interview with Lionel Fogarty’, Poetry International, http://www.poetryinternationalweb.net, July 10, 2011

6. ibid.

7. Ball, Timmah, ‘An Interview with Poet Lionel Fogarty’, Etchings Indigenous Treaty, Ilura Press, Melbourne, 2011, pp. 129-135

8. Cooke, Stuart, ‘Tracing a Trajectory from Songpoetry to Contemporary Aboriginal Poetry’, A Companion to Australian Aboriginal Literature, edited by Belinda Wheeler, Camden House, Rochester, NY, 2013, p. 104

TIM WRIGHT has poems included in the anthology ‘Outcrop’ (Black Rider Press, 2013). He recently constructed a chapbook, titled Weekend’s End.